When I was young, there was always something missing in me.

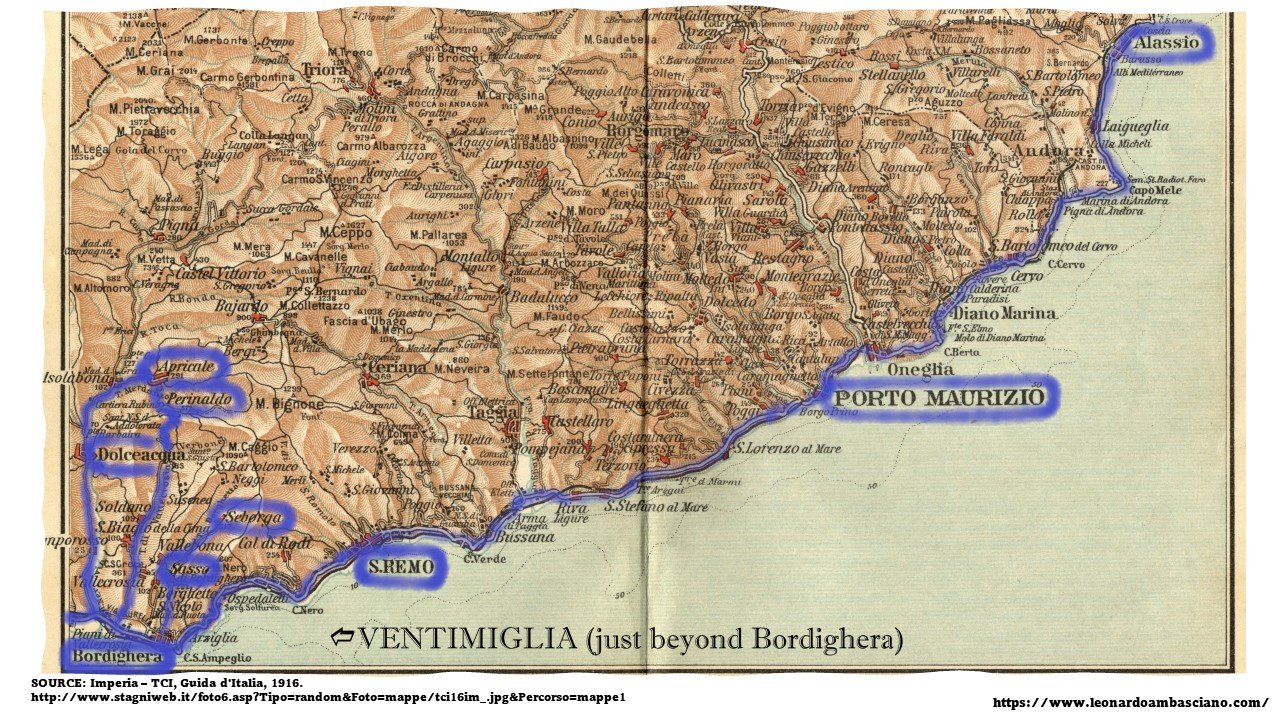

Everywhere I went, I felt like I didn’t belong, like I couldn’t belong. My father left his seaside hometown in Liguria for Turin, a huge industrial city at the foothills of the Alps, in the 1970s, and from there he went abroad in the 1980s, taking his family with him. When I was three years old, my family decided to leave Bruxelles and travel back to Turin but, by that time, my father had already started globetrotting for work. We started spending give or take half a year in Turin and half a year in Liguria, some time in my father’s seaside town and some time in my mother’s Ligurian mountain hamlet. This crazy schedule meant that, by being eveywhere for short periods of time, we couldn’t really put down good roots anywhere. Which only added to my feeling of overall displacement, identity confusion, and sense of alienation.

As a coping mechanism, I’d try to mimic the local speech patterns. I started talking to myself to train my ear, whether out loud or just in my mind, instinctively picking up accents and some key words or espressions here and there. (I also remember my mother being this sort of weird linguistic chameleon, and it is easy for me to imagine her doing the same when she was younger). My aim was to camouflage in the midst of my peers, but I always ended up being too self-conscious to feel at ease. So, most of the times I retreated in my safer mental world.

I was taught standard Italian at school in Turin, which I felt was not that useful on the field, because whenever we were in Liguria, my parents mainly spoke Ligurian (and two variants at that too) with their own kith and kin. I felt excluded, marginalised. I wanted so bad to learn ingauno or bardinetese as a way to reconnect with my relatives and really feel part of the family.

Since my father was away from home most of the times, I turned my attention to my mother. For a brief period of time when I was 9 or 10 years old, during our extended Ligurian residence, I used to bring a notebook, a pen, and an Italian dictionary with me. Whenever I’d find my mum alone in my paternal grandmother’s kitchen, I’d sit at the big metal table and start asking her to translate on the spot the words I’d read from the dictionary. She knew French pretty well, so I figured out that she might have helped me with the transcription of certain Ligurian phonemes that are absent in Italian (it goes without saying that I didn’t know anything about dialectology, IPA charts, and unified standard writings at that time). My efforts were fruitless, and I felt so dejected after my vain attempts at decoding my family’s secret language. My mum always seemed to feel almost embarassed at first, making up excuses for not knowing the real words – her aunt knew the real, ancient word for that specific Italian noun, her cousin should know the real verb to define that action. There was always someone else to ask (most of the times unavailable or long dead). It was never she the one who really knew. Years later, in my adolescence, I resented her for her unwillingness to teach me, but she had a point. Language does evolve with time, and many of the words used by her relatives thirty or forty years earlier were not the ones she would employ. However, there is no original, pristine, and unadulterated form of a “language” to retrieve (“dialects” included) because language has always been constantly evolving: “one’s grandmother no longer spoke like her own grandmother” (Toso 2006: 185).

Soon, my mum’s embarassment would turn into sheer annoyance. Patience was not her forte, and I learnt the hard way that knowing is not the the same as teaching.

When I was 11 years old, my mum gave me for Christmas the reprint of a 1968 Italian etymological dictionary. A politically correct way of saying stop pestering your mother, for crying out loud! Alas, no Ligurian in sight here, except for the odd loanword like camallo or mugugno. 2023 Leonardo Ambasciano (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

I remember thinking that maybe she was not that good at speaking bardinetese and inganuno (which she had learnt to fit in my father’s hometown). Was I imagining things? No, because, to my utter dismay, bardinetese was all she spoke with her relatives on the phone or live. Never with me.

There was something deeper going on, and it took me years to understand what that was. Her intuitive strategy, as it were, was to divert attention from my relentless requests (and quickly shut them down) because she had internalised the idea, instilled through post-war compulsory education, that Ligurian was a poor, second-rate form of communication (with bardinetese as a basilect on the Riviera), an inferior “dialect” conceptualised as a deformed, underdeveloped variant of the literary and prestigious Italian favella. This bogus and pseudoscientific claim was fuelled by the political remnants of Interwar chauvinism and engineering of a (re-invented) national tradition. Yet, this viral meme served its original purpose, and as a result my mum was unconsciouly ashamed of talking in her own mothertongue with her own son.

Italy has a millennia-long history of macroregional, independent city-states. There is no such thing as unified Italian people, nor is there a God-granted language set in stone once and for all. Ancient Italy was a poutpourri of non-Roman, non-Latinophone, and even non-Indoeuropean peoples and cultures (Etruscans, Greeks, Celts, Phoenicians, Venetics, Umbri, Oscans, Ligurians, Sardinians, etc.), and while they were all Romanised and Latinised in time, mostly through non-pacific means, their descendants retained some specific words (often preserved in local toponymy) along with distinct linguistic features that possibly survived as substrata (for alternative hypothesis see Varvaro 2001: 215-223). The Italic peninsula was heavily colonised by Latinophone Roman citizens in different waves, and under the Roman empire the politically unified Belpaese became an unprecedented Mediterranean and European crossroads for, if not a melting pot of, different peoples and cultures. Then, Late Antique Völkerwanderungen, Mediaeval conquests by Normans, Byzantines, Arabs, and a sequence of neverending military campaigns led by competing European kingdoms well into the 19th century, contributed to the generation of ever new linguistic adstrata and superstrata, and managed to create one of the most complex linguistic, cultural, political, and genetic mosaics of Europe. If we add the Mediaeval prestige of Provençal literature, the innovative Sicilian School, the ongoing influence of classical Latin and Greek as sources of erudition (with the former continuously employed as administrative, legal, and bureaucratic language well into the Renaissance – and sometimes even beyond), as well as the literary and cultural influence of French, Spanish, German, and, in modern times, English, you can have an idea of the various forces that exerted their differential influence on the various Italian “dialects.”

Major linguistic families in the Italic peninsula. Please note that this map is not the territory: this is a simplified cartographic representation that ignores important local variations, relevant variants, non-Romance languages, and several additional isoglosses for the sake of the bigger picture. Also, please note that not all linguists agree on the Tuscan affinities of Corsican, and that the Central Italian Romanesco “dialect” (spoken in the metropolitan city of Rome) has been heavily influenced by Tuscan since the 16th century. Source: Lee (2000: 176). Note: on the rather peculiar position occupied by Ligurian among the Northern Italic “dialects”, see Toso 2009b: 18-20.

If one of those macroregional languages rose to prominence it was because of the contingencies of history – and the undisputable artistic prowess of a few literary giants from Tuscany. Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, who wrote in Latin and in a heavily reworked late Mediaeval Florentine vernacular, towered among their contemporaries, but their native language was spoken just within the borders of Tuscany. However, the sensational success of Dante’s Divine Comedy, in particular, “was the Trojan horse behind the success of the Tuscan language”, as poets and writers, especially in the Northern regions, began to try their hands at “Tuscanising” their works (Marazzini 2002: 214). Roughly one century and a half later, under the pathbreaking and forward-looking linguistic politics of Florentine rulers Lorenzo il Magnifico and Cosimo I, the local vernacular in which those three authors wrote was promoted as the semi-official template to shape and codify a new regional standard. The international and commercial importance of Tuscany during the Renaissance was another relevant factor: the prestigious Florentine vernacular was slowly being adopted by local courts and signori elsewhere as an administrative koinè to replace Latin, now unintelligible to the people, as well as to engage in diplomatic relations with other macroregional powers whose mutual linguistic intelligibility ranged from potentially acceptable, to challenging, to almost nil (Marazzini 2022: 106-108). By that time, intellectuals and writers all over the peninsula were already contributing to the growing, but still informal, “Italian” literary canon by adding their own works to those authored by the celebrated Florentine forerunners, slowly but surely transmogrifying that prestigious vernacular into something different. Fast forward to the Risorgimento, and this ever-growing literary corpus, now developed into regional “Italian” variants, would finally provide the raw material for an elite of political engineers to establish the modern “Italian” language (curiously, around the same time, Romanian was going through a similar process of national reinvention, but the faction that vigourously supported an “Italianisation” of the language lost in favour of the more politically appealing, but less linguistically warranted, “Francisation” of modern Romanian; cf. Lupi 1968: 58-59). However, Florentine continued to evolve naturally in its Tuscan “ecological” setting, as it were, while the Italian lingua franca of the Italic peninsula remained artificially frozen in time just like the other standardised national languages of 19th-century Europe, to the point that Florentine and Italian today are far from being the same language (Marazzini 2002: 469-471).

I think it important to note that, by virtue of its location and internal linguistic developments, Italy hosts several different Romance language systems with distinct phonetic and grammatical structures as well as a bundle of isoglosses (collectively indicated as the La Spezia-Rimini Line) that some linguists consider a major division between Western and Eastern Romance languages. This is to say that the other Italian “dialects” are not inferior forms of that prestigious Florentine “language” – ignorant and brutish “dialects” to be forgotten: each one represents the local form of popular Romance language continuously spoken in situ ever since Romanisation, not to mention that most of them were the de jure or de facto languages of independent city-states and kingdoms from the very early Mediaeval period until the unification of Italy! Apart from artistic considerations and ahistorical teleological thinking, how could Mediaeval Florentine be considered the perfect linguistic norm from which other Italic Romance “dialects” more or less diverged? (Especially considering that Tuscan itself is a diverging and conservative outlier in the context of major Northern and Southern “dialect” families; Marazzini 2002: 214). And yet, I was taught a weak version of this pseudoscientific and dialect-delegitimising paradigm in elementary and middle school, while my parents – and even more so my grandparents – underwent an even stronger pressure to discard their native “dialects.” And by doing so, the nine or eight century-long literature written by regional authors in local vernacular was almost completely erased from history: it was either the Italian way or the highway.

Dominance (our official language) and subordination (your informal dialect) in action: “The teacher should bear in mind that these little manuals should not be used to teach the dialects [‘i dialetti’], which the students already know perfectly, but to teach the language [‘la lingua’] through it.” From Teresa Giaimo’s Translation Exercises from the Ligurian Dialects: Genoese (1924: 5), my emphasis. Source: Internet Archive.

All artistic and aesthetic considerations don’t mean a thing without politics: in the end, a language is just a dialect with an army and navy. The spread of literacy, the success of literary works, the diffusion of modern mass media, urbanisation, bureaucracy, industrialisation, and, most of all, compulsory education are all obvious, but secondary, contributing factors. Indeed, a case could be easily made for stating that the more or less violent, top-down imposition of national languages in modern Europe, including the local “war against the dialects” conceived as “an obstacle on the path to the ideal” of national Italian unity (roughly ranging from the Risorgimento to the Post-war economic boom), was part of part of the same imperial, xenophobic, and colonial project that hijacked and distorted the Enlightenment call for universal education, social progress, advancement of knowledge, and mutual intelligibility for its own nationalistic and belligerent goals (cf. Marazzini 2002: 109-111; cit. p. 109). However, I would be remiss not to point out that a significant number of people in the regions that were conquered, annexed, and subordinated had been active participants in the abandoment of their native languages. Michel Foucault wrote,

What makes power hold good, what makes it accepted, is the fact it doesn’t only weigh on us as a force that says no, but that it traverses and produces things, it induces pleasure, forms knowledge, produces discourses. It needs to be considered as a productive network which runs through the whole social body, much more than as a negative instance whose function is repression (Foucault 1980: 119).

After the Risorgimento, the old “dialects” simply became useless to thrive in the “productive networks” of the new nation-state. As linguist Fiorenzo Toso noted with a touch of Foucauldian biopower,

The conditions governing the choice of Italian over Piedmontese or Alpine Provençal are more about social promotion than about oppression, as is sometimes rather convenient to think. The institutional murder of “dialects” in Italy would have been quite futile and arduous to implement. It is far better and cleaner to let them commit suicide. The powers that be should be blamed instead for their blatant disregard of the enormous cultural heritage that has been allowed to dissipate, and for the extraordinary potential that has been lost by not assigning a leading role to the minor and regional idiomatic realities through multilingual education and practice (Toso 2006: 279; my translation).

And so, having internalised this top-down censorship on local mothertongues, we never spoke Ligurian at home. Yes, there were bits and scraps of both ingauno and bardinetese here and there on a daily basis and the occasional entire sentence, sometimes mixed with French and even piemontese (it was mainly my sister who picked it up in high school and brought it home), but never a full interaction in my mum’s mothertongue. Not with me, at least. And yet, when after all those months in Turin my mum returned to her hometown during Christmas, Easter, and summertime, Ligurian was all she spoke with her relatives. And I could always hear her all year long talking in bardinetese on the phone too. That’s why I became more adept at understanding Ligurian than speaking Ligurian. Her self-unacknowledged diglossia turned into an intergenerational communication handicap. I see now that while in Turin, with no one else to talk to during the cold, grey, and polluted winter months of the 1980s and the early 1990s, she must have felt as isolated and sad as I was.

I might have coopted my nonni (Italian for grandparents) to find a way to finally crack the code of this melodious language I was hearing all the time, but they were too old. And most of all, totally uniterested in me. The feeling at that time was quite mutual, I’d say. My maternal grandfather and my paternal grandmother, whose mothertongues were two distinct Ligurian variants and to whom Italian was a second language at best, never had any sort of meaningful relationship with me: in their own ways, they were both unempathetic and cold. That was because of their own personal experiences, both hardened by the loss of their respective spouses. I came perhaps too late in their life, and I remember them as the tough farmer ultimately broken by a life of hard work in the fields, and the authoritarian widow with a stern military outlook who was once married to a maresciallo. While I used to resent them for their emotional distance after they were gone (and I still feel the emotional void they left in me), I can now understand their sad backgrounds.

I distinctly perceived the language barrier as a wall between my family and me, and I wanted to fit in to become part of the world my family seemed to inhabit so effortlessly. Spoiler alert: I’d never fit, I always remained the one from the big city “up there”, at the foothills of the Alps. Which prompted me to distance myself further and further from my relatives in a loop of self-loathing. I remember all the times my maternal cousin-in-law asked me, in front of both families, if I felt more torinese or more ligure, as if I was a Wunderkammer curiosity or a trapeze artist travelling with the circus. I can’t remember my answers. I only recall his cheerful insistence, my lopsided smile, and the ever-growing divide between Us (all my relatives along with my parents) and Them (the outsiders, those from another region, those who come from an industrial metropolis far away, those who don’t speak our language, those who don’t belong – me). I know it was not a question posed with ill intent, far from it: it was merely my cousin-in-law’s idea of a meaningful interaction with a kid.

Whether desired or not, the end result was a rigid social demarcation that made me feel like I couldn’t belong. The self-hatred was aggravated by the languages I had to learn at school – English since elementary school, to which French, Spanish, and Latin were gradually added. Then, while at University, I even studied Romance Linguistics and Romanian: why wasn’t I allowed to learn the language spoken by my family? (Well, for starters, I was studying in another region, that’s why, Einstein, but I was too naïve to understand this trivial point at that time… however, as far as I can remember, no class on piemontese was available anyway). And in Turin, where the growing feeling of alienation was starting to affect my relationship with the city as a whole because of family problems and personal identity issues, I had to keep it to myself, grinning and bearing it each time I heard some schoolmates or university colleagues inserting a few words of, or even exchanging full sentences in, piemontese, pugliese, sardo, o siciliano with their parents and friends. Not that they were that many, mind you, but it was like I was able to focus just on them to fuel my sense of alienation. (By now, the coping mechanisms I developed as a kid had become maladaptive.) I didn’t have any friend from Liguria there, and I envied them (it didn’t help that I didn’t have that many friends, period). And I secretly hated them for being so tight-knit, and I secretly hated myself for hating them. And since I internalized the shame and the cognitive dissonance nurtured by my father, according to whom dialect-speaking was a sign of ignorance, illiteracy, or despicable and chauvinistic regionalist separatism (he who usually conversed in ingauno with his own friends and relatives!), I blamed myself relentlessly for thinking that I was missing out on a core experience in the creation of both my personal and collective identity.

My father’s partially destroyed copy of Bruno Migliorini and Ignazio Baldelli’s Breve storia della lingua italiana. Florence: Sansoni (3rd edition, 1967). I basically saved it from the trash bin more than twenty years ago, because it didn’t seem like he cared much anymore. 2023 Leonardo Ambasciano (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Those powerful negative feelings were constantly evoked as I felt excluded, again and again, when faced with the distorted mirror of a family in which I couldn’t really see myself.

Where there were faces I could see nothing.

Where there were voices I could hear noise.

That was the tipping point. Turin – not the magnificent Turin featured on modern-day postcards, the Baroque jewel, the royal capital, the cultural powerhouse, and the industrial hub – but my personal Turin, the Turin of my upbringing, of my dark winter days, of smog as thick and grey as ink, of unbearable traffic noise, of my illnesses, of my broken family, of my isolation, of me being bullied and beaten at school – was becoming toxic for me. For all intents and purposes, I was an immigrant, a stranger. I could never truly belong there.

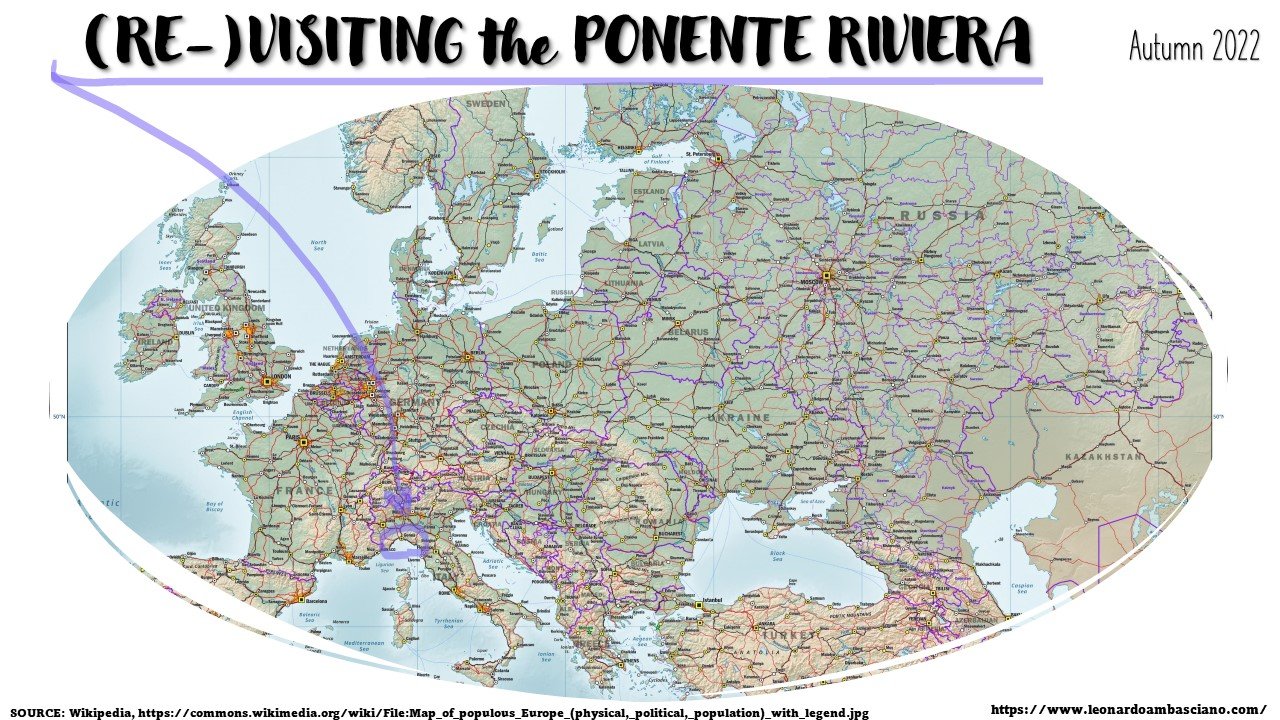

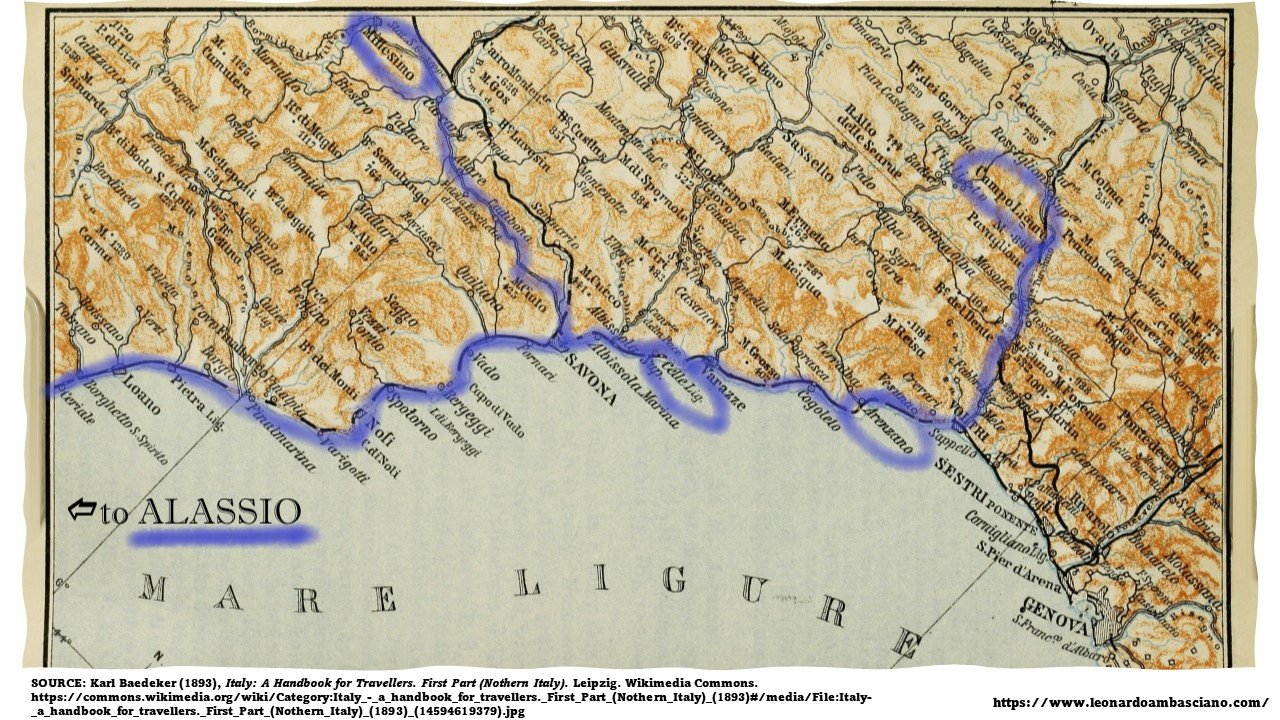

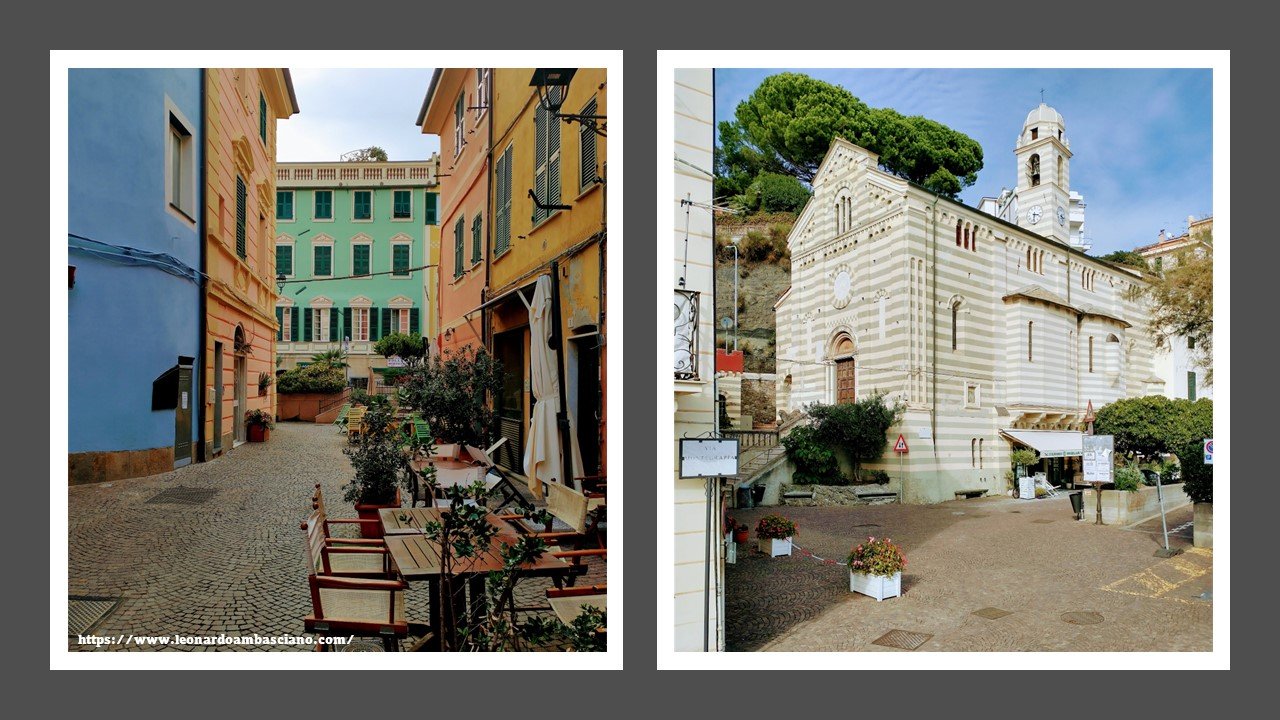

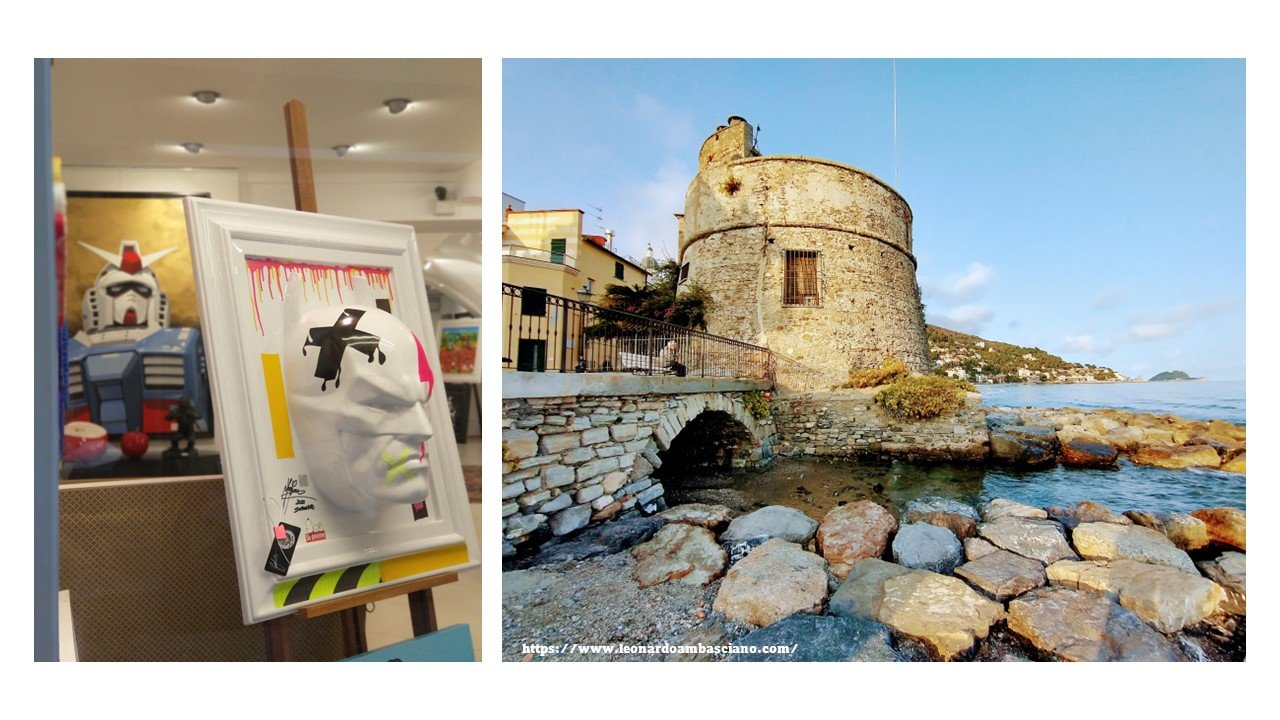

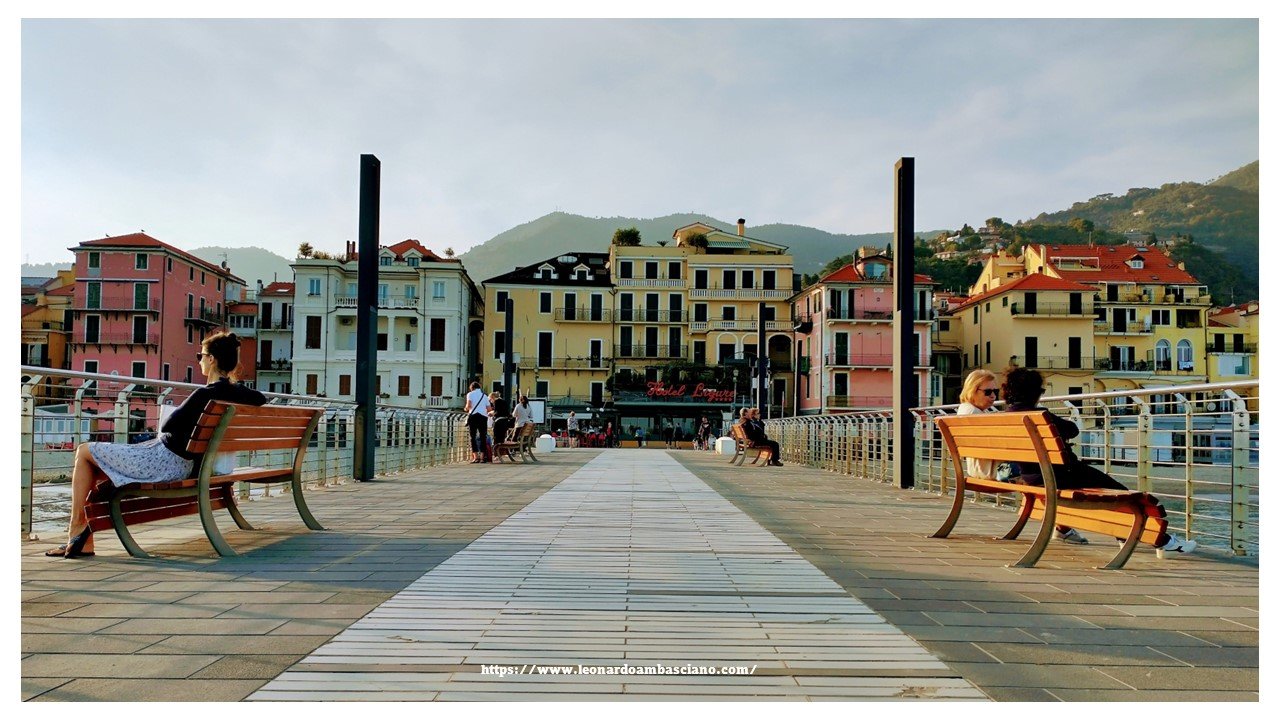

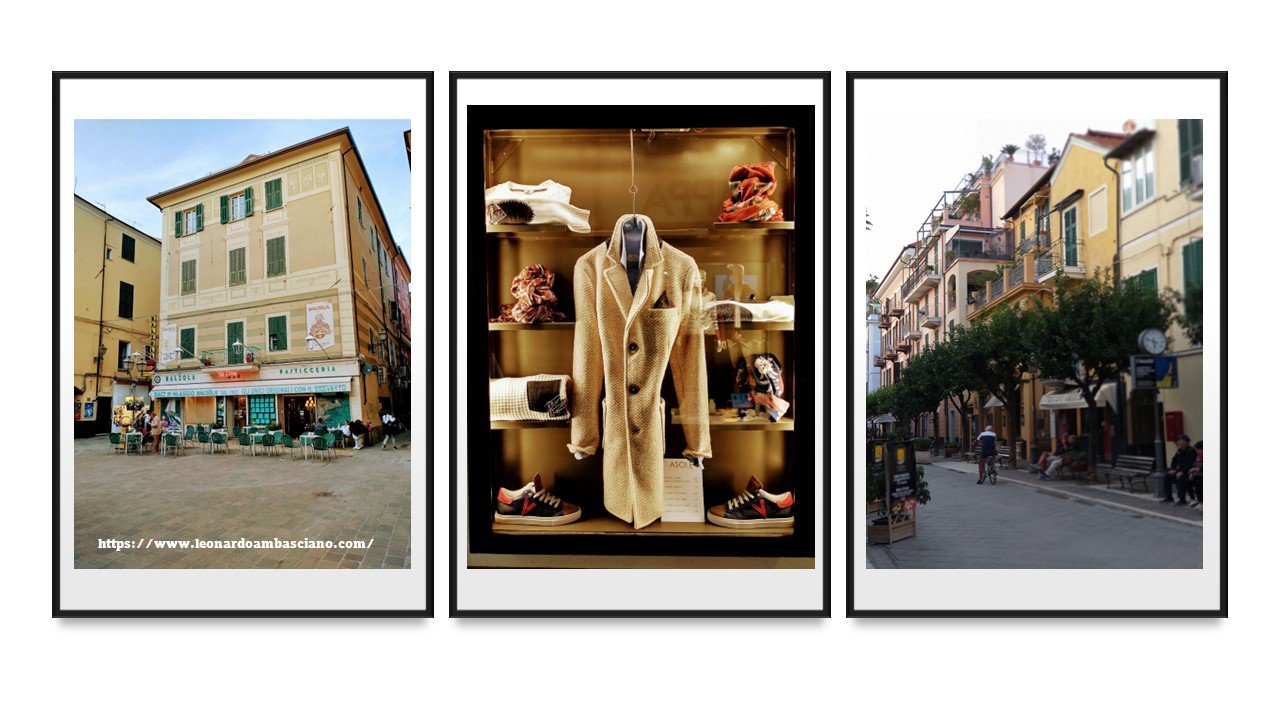

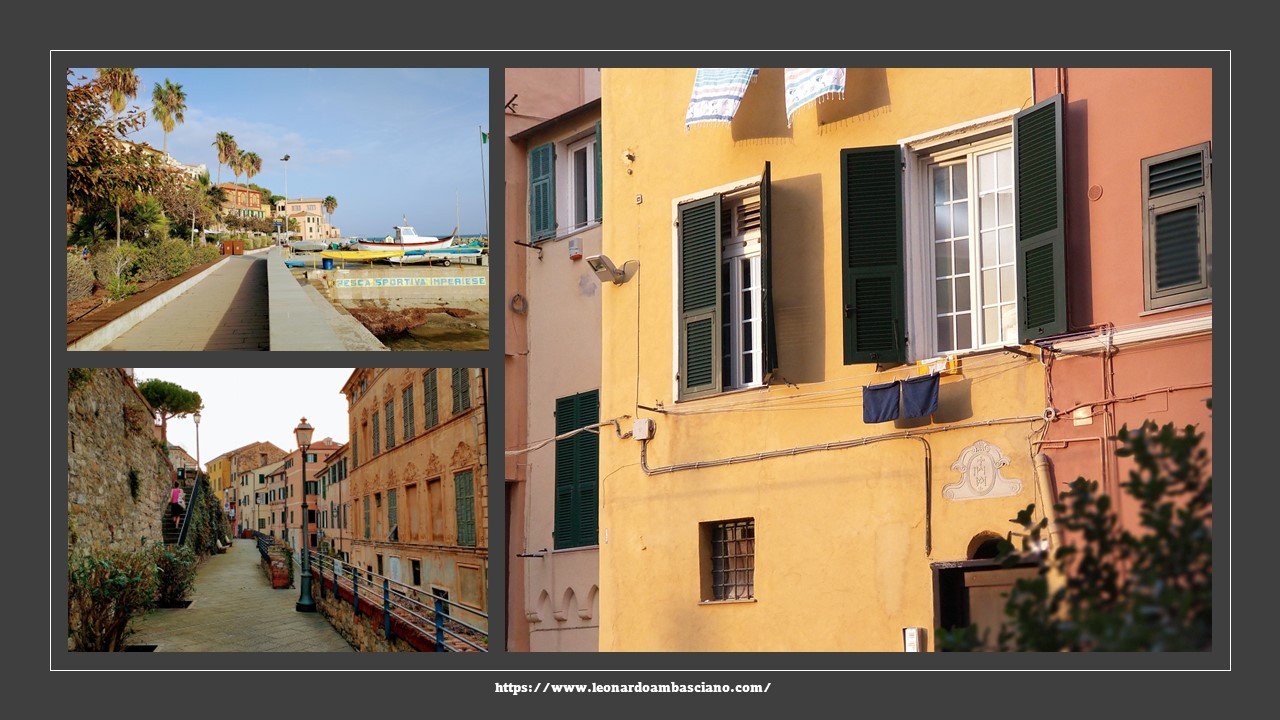

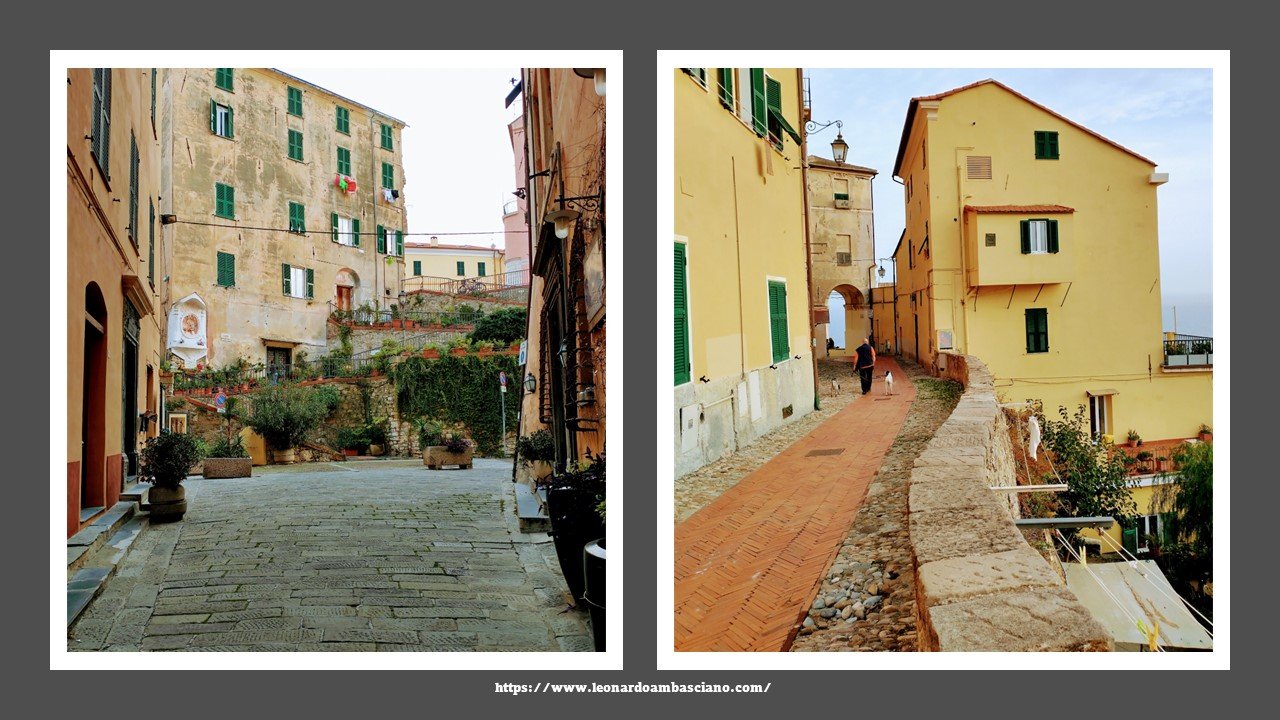

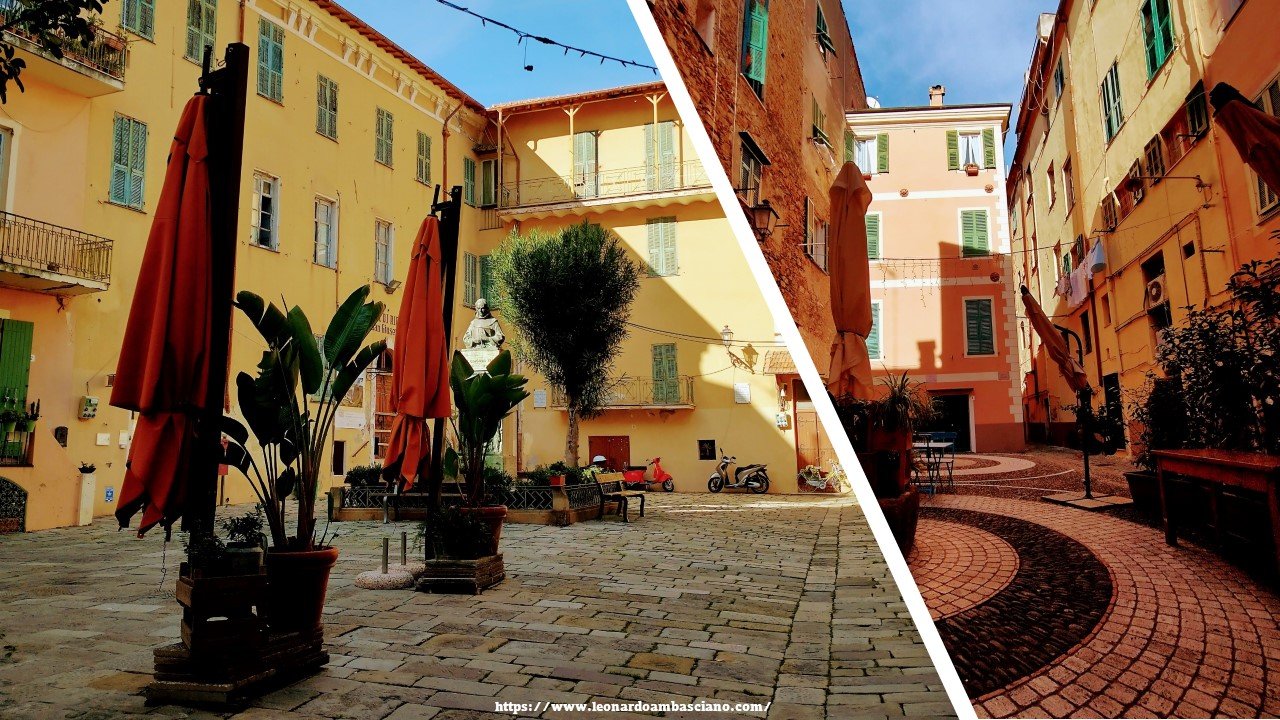

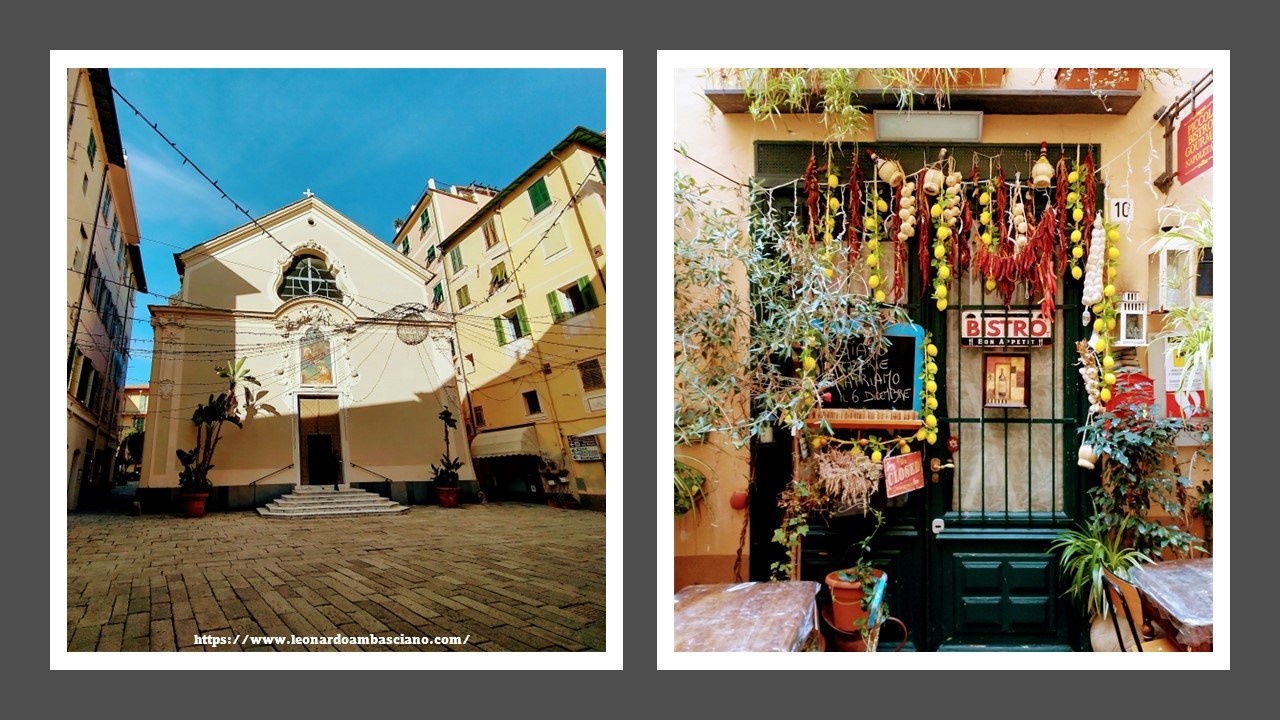

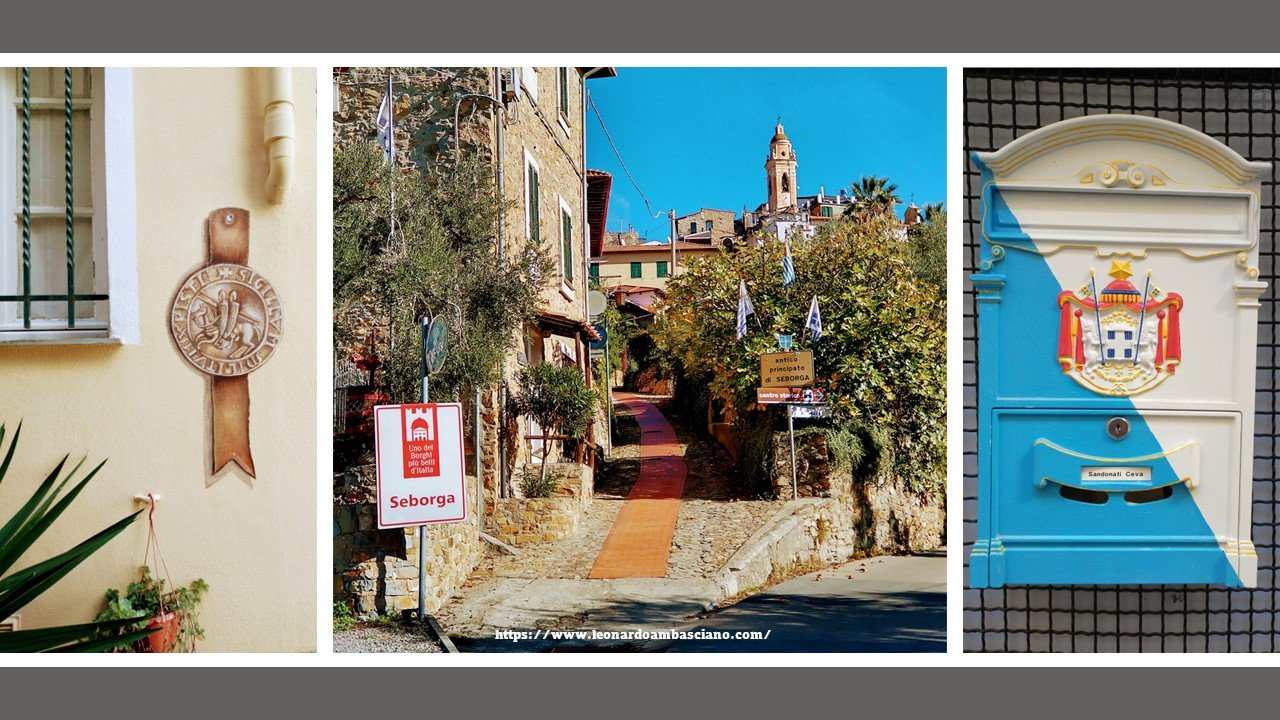

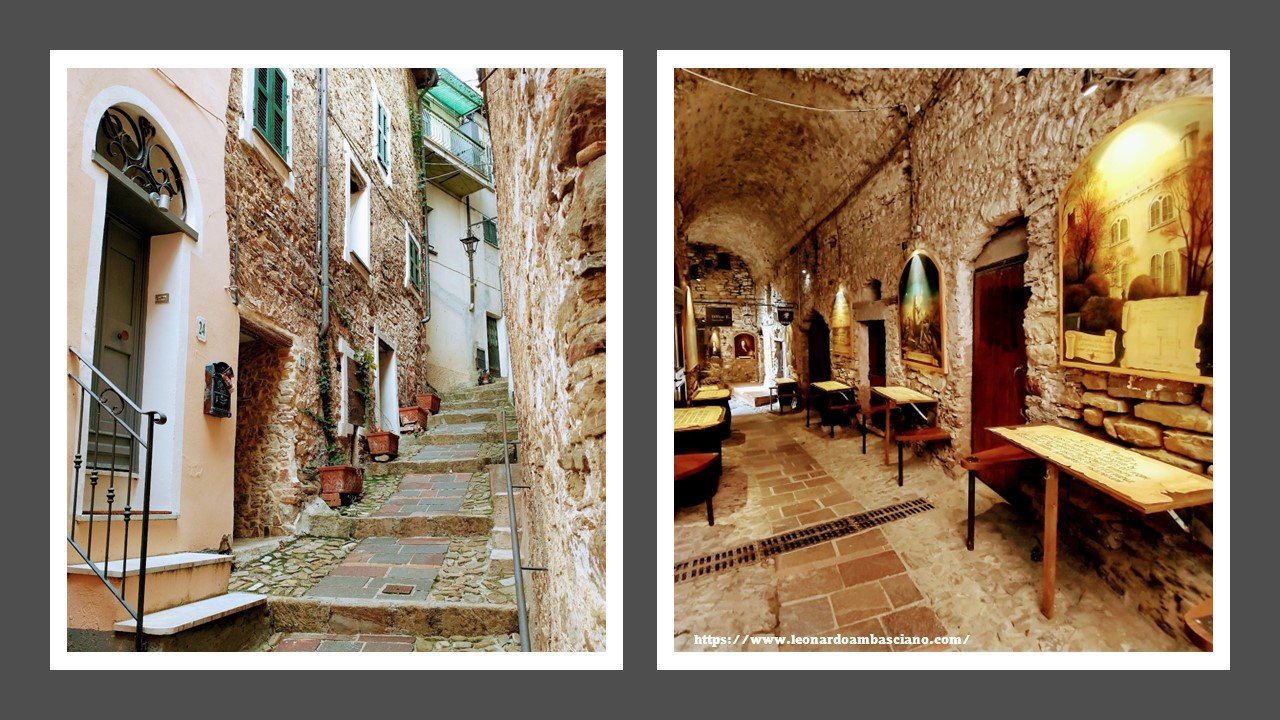

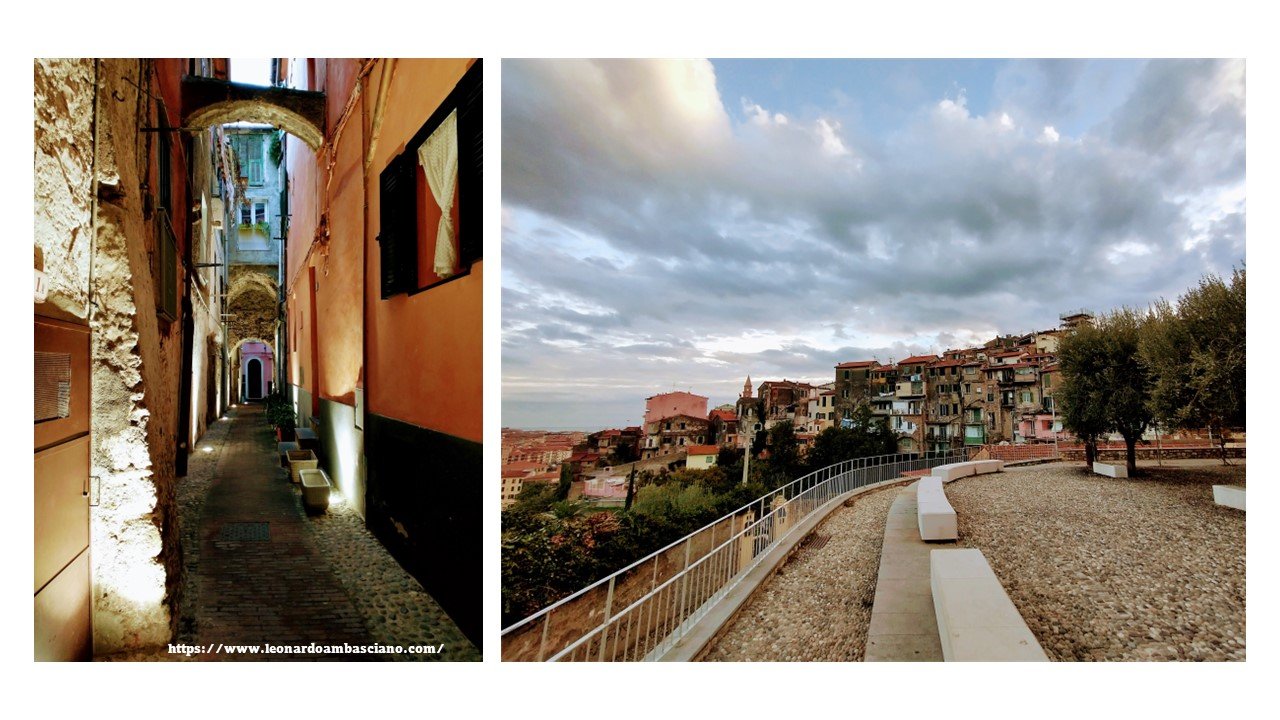

And this is why, after all those years and more than a fair share of relocations, during the pandemic I finally decided to visit Liguria little by little, whenever I can, in an ongoing effort to reclaim a part of my identity, the part that was denied to me when I was young. (I also started reading an anthology of Ligurian literature, which definitely helps when it comes to the historical appreciation of the places I visit beyond their merely aesthetic urban qualities.)

However, I discovered, much to my dismay, that there is no comprehensive dictionary or grammar of ingauno, and least of all, of bardinetese (I mean, there are dialectological articles and academic contributions, of course, and Genoese dictionaries and grammars are always in print, but no updated, modern handbook is available for both Ligurian variants as far as I know – and they are definitely not Genoese). I don’t want these languages to die. No language should ever die. As Toso poignantly wrote:

[…] Linguistic homogenisation, like any other form of homogenisation, represents an impoverishment of diversity, as language itself is a characteristic element of the human species […]. In addition to being a means of communication, each language represents a specific view of reality, a different perception and conception of the world that deserves respect and attention far beyond its actual practical utility in the global linguistic marketplace. Genoese, for example, lacks a word for expressing the concept of “rain” and does not distinguish between “sleep” and “dream”; the concept of “green” in Welsh extends to much of what we define as “blue”; Italian lacks a significant number of specific terms used by the Brigasco shepherd to define the various ages and conditions of his livestock, as well as those employed by the Tabarkine tonnarotto to identify different “cuts” of fish; in Eskimo languages, there is no word for “tree,” but there are dozens of terms to indicate the consistency of snow and ice. [...] Therefore, the demise of a dialect entails not only or not so much the abandonment of “knowledge” or manual skills, but also of entire taxonomies and complex systems for organizing reality (Toso 2006: 280; my translation).

I can see those linguistic Weltanschauungen dying in real time whenever I hear some elders talking in Ligurian and the local youth talking in Italian, and while the process of “dialect” obliteration has slowed in recent decades (with the youth increasingly reclaiming Ligurian – in true Foucauldian fashion – to reinvent Italian, resist assimilation, and build their social identity as part of a local diglossic process), Ligurian is currently classified by UNESCO as “definitely endangered – children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home.”

When I was in high school, I went through a phase of full-fledged resentment and rejection of my family roots. My thinking was something to the effect of, “fine, if my parents failed to teach me, if it’s really not in their interest to teach me, then I don’t see why their language should be of interest to me. I don’t see why I should bother to learn it. It’s their loss – it’s their own culture that will perish.” In this sense, Toso correctly noted that:

The preservation of a language arises from collective consciousness and willpower [...]. The responsibility for abandoning the dialect lies with the [generation of parents]. To save the dialect, it must be spoken and transmitted to one’s children (Toso 2006: 285; my translation).

But what about my generation? What about those who were not taught the language? As I grow older, what I increasingly feel is the heartbreaking bitterness for the avoidable loss of the mental “taxonomies and complex systems for organizing reality” behind the words I’ll never know. And what I’m left with is regrets for a past that I’ve been denied. (And if this is my personal experience on an insignificant, almost microscopic scale, basically all set within the same geohistorical macroregion, I can only imagine the sheer pain and the amount of almost insurmountable difficulties immigrants from radically different linguistic settings might experience.)

Accepting this loss, while trying to rediscover my roots, is hard. I need to make peace with the fact that some missing pieces of my identity puzzle are lost forever. No amount of language learning will ever replace the lack of interaction with my relatives when I was a child. I wasn’t socialised into Ligurian, and I’ll never be. No amount of intellectual and linguistic knowledge will ever fill this void.

To overcome this loss, the first step was to come to terms with the fact that what’s lost is lost and that it’s not my fault. Second, I had to learn how to forgive and love myself despite missing what I thought were some key pieces of my family identity. Third, I had to come up with an effective strategy to try and neutralise this overwhelming sense of loss and grief as quickly as possible.

After much deliberation, this is the solution I came up with.

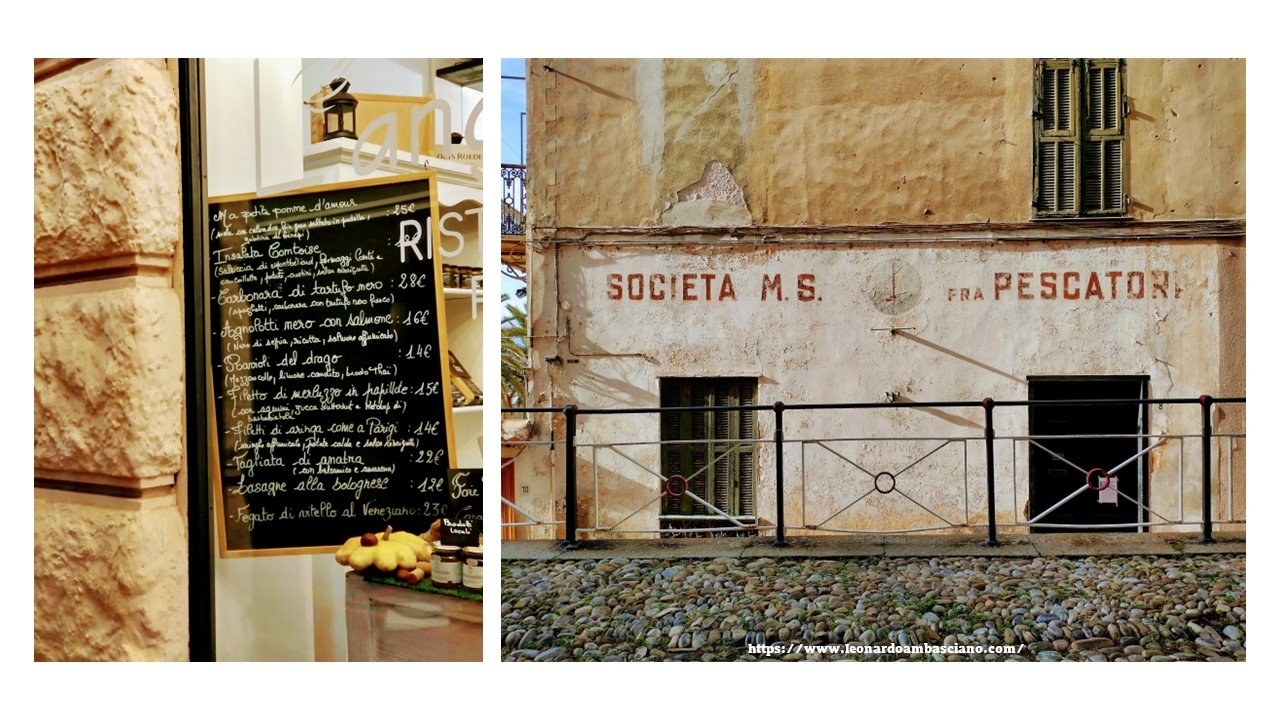

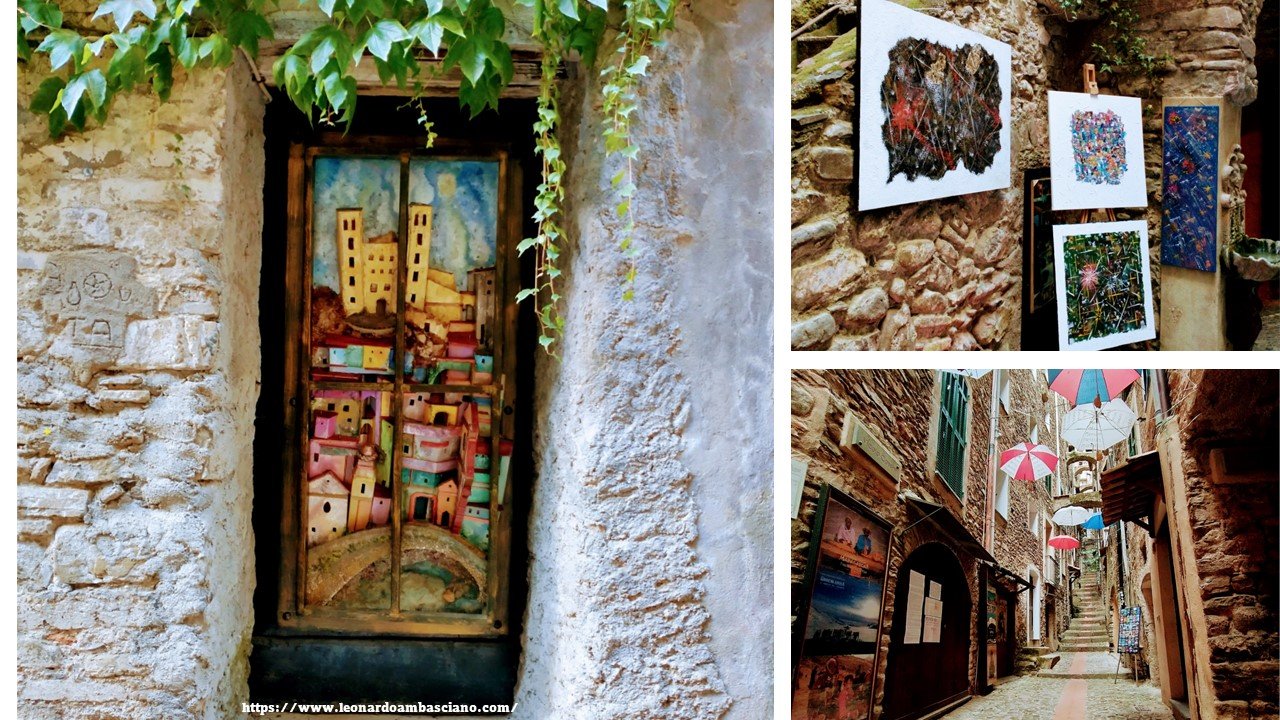

I thought that a renewed, creative, expansive understanding of my heritage could help pave the way towards my liberation from the curse of not belonging anywhere. Just like you do when you re-pot a house plant in a larger pot to fit the plant’s growing cycle, I decided to “re-pot” mysef into the larger regional “pot” of Liguria as a whole. By doing this, I counterbalanced the loss of my parents’ local knowledge, limited to a specific and limited geolinguistic area, by embracing a larger personal identity, changing my goal from an unachievable linguistic fluency in bardinetese or ingauno to a cultural and emotional identity as a Ligurian (“ligure”) tout court. Now, whenever I have the chance to visit some Ligurian towns, I listen to the people talking in the caruggi or waiting to buy a slice of tasty fugàssa, delicate and nutty revzöra, hearty turta pasqualìnn-a, or delicious pisciarà, and I enojy what I can understand in the moment, while trying to decode what I can’t. Every time I learn a new word, I’m filled with joy and hope, as if I finally found one of the missing pieces of a puzzle. What I don’t understand, it’s gone, and it’s fine. With each visit I’m rebuilding my own identity right there. That’s all I can do. And if I have to build a personally meaningful mythopia to unlearn my self-hatred, so be it: it’s better to live in a Ligurian dream than survive in a post-industrial wasteland.

On Thursday 20 October 2022, while visiting Arenzano, near Genoa, I came across this death notice on a wall, announcing the funeral of probably the most important academic scholar of Ligurian language and literature, Prof. Fiorenzo Toso. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) 2023 Leonardo Ambasciano.

I would like to end this autobiographical post by including below a poem written by former assistant researcher at the University of Genoa (1972-1981), Giannino Balbis (1948-). Balbis is a Mediaeval historian, a scholar of literary studies, and an accomplished poet himself. More poignantly, he comes from the same hamlet my mother comes from, and he’s fluent in the dying bardinetese language (the town has a grand total population of 751 souls, and I’d say that only two thirds of them might be really fluent in “old” bardinetese). You will find below “I mei veï” (My elders), the existentialist poem by Balbis that Toso chose to include in the seventh volume of his anthology La letteratura ligure in genovese e nei dialetti locali (Toso 2009b: 181-182, transcribed according to Toso’s simplifed spelling) as well as in Liguria linguistica (Toso 2006: 240, transcribed as originally intended by the author in Balbis 1985: 21, and the version I chose).

I mei veï

U trijnonnu Lanéttu,

quand’è balle i gi’’âvan au riondu,

u ti’’âva du’ crišti e in trondemondu.

U bijnonnu Pinsei,

quande a futa ai jmangiâva an-t-è man,

u špiâva dui crišti e trèi cratàn.

U mesé Giusepéin,

se u presiméin u i muntâva che leva,

u giaštemâva cu-ina porcaeva.

Me pâ, che l’è Achile,

se u nervušu l’è au curmu, mile

vote u tâxe per in porcufürmine.

E mi, ch’è ne sö ciü chi è son,

quande l’anguscia a me monta an-t-a gu’’a,

u ni è versu de fâla ca’’â. E alu’’a

u ni è bragiu cu tegne, ni rajón.

Mi è vivu an-t-u tèimpu balurdu

du Scignù che l’è vignüiu surdu.

Here’s my English translation (please note that the staggering and quite inventive variety of local imprecaçioi and giastèmme is far from being fully represented by the swear words actually available in English):

My elders

The great-great-grandpa Lanéttu,

when things got on his nerves,

he’d burst out a “damn it all!” and spew a couple of “Christ!”.

The great-grandpa Pinsei,

when he could feel his nerves tingling in his hands,

would spit out two “Christs!” and three profanities.

Grandpa Giusepéin,

if anger overwhelmed him,

would cuss with a “bloody hell!”.

My father Achile,

if anger reached its peak,

for a thousand times he’d refrain from cursing after a “gobshite!”.

And I, who no longer know who I am,

when anguish rises in my throat,

there’s no way to make it ebb. And then,

there’s no scream that might release me, no reason that can prevail.

I dwell in this ludicrous time

of a God who has gone deaf.

A huge, if belated, thank you to Toso for providing readers with an Italian translation in prose, much appreciated, to Balbis for keeping bardinetese alive, and to my mum, for helping me, at long last, with the translation of a few words. Gràçie.

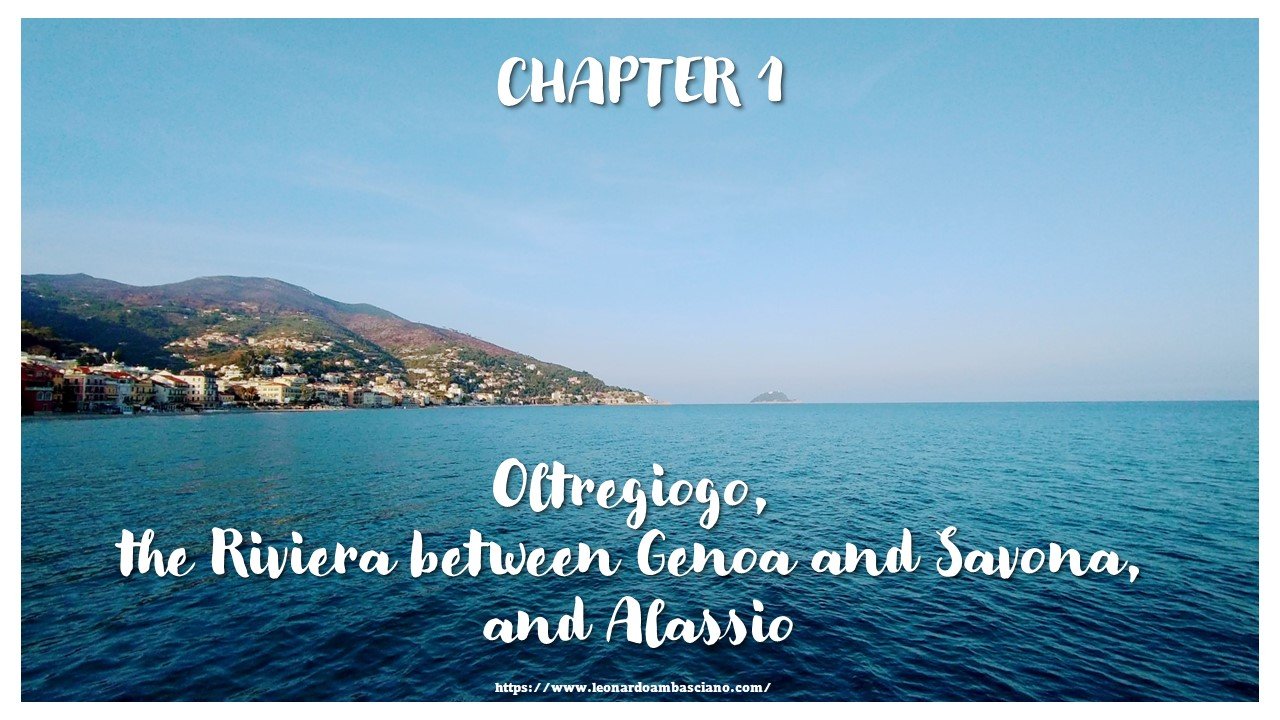

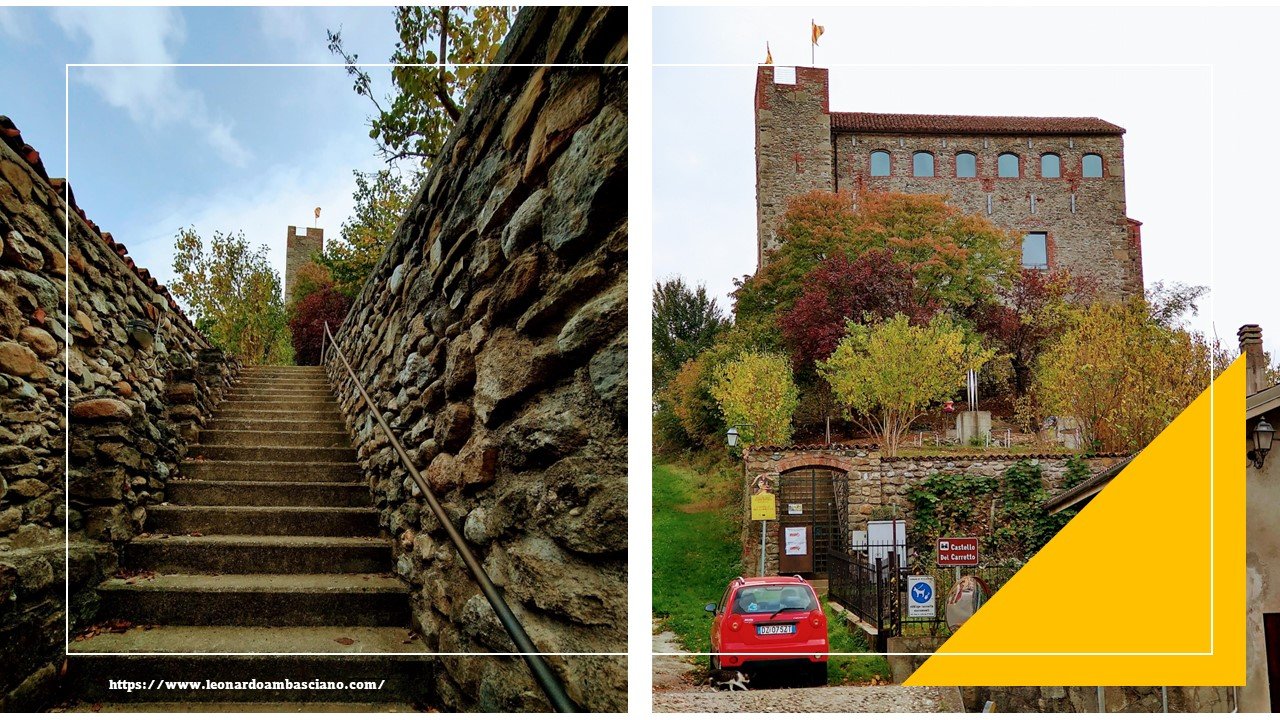

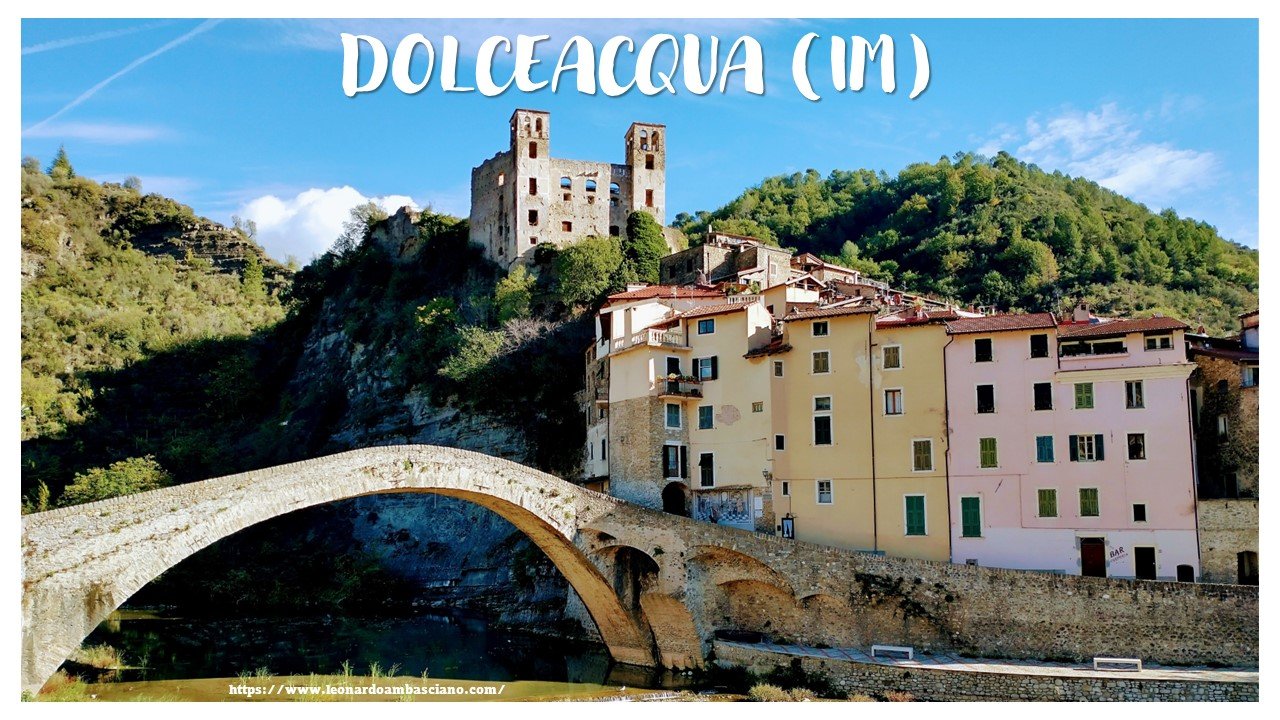

And now, with a long delay and an even longer personal detour, here’s the third leg of the travelogue to one of the most beautiful regions in Europe (change my mind!).

Check it out!

ALL PHOTOS BY LEONARDO AMBASCIANO, 2023 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) EXCEPT WHERE INDICATED OTHERWISE.

Refs.

Balbis, G. 1985. Trondemondu. Versi in dialetto bardinetese. Illustrazioni di Gianni Pascoli. Rocchetta Cairo: G.Ri.F.L.

Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews & Other writings 1972-1977. Edited and translated by C. Gordon. New York: Pantheon.

Giaimo, T. 1924. Esercizi di traduzione dai dialetti della Liguria: Genovese. Florence and Turin: Bemporad/Paravia.

Lee, C. 2000. Linguistica romanza. Rome: Carocci.

Lupi, G. 1968. La letteratura romena. Firenze: Sansoni.

Marazzini, C. 2002. La lingua italiana. Profilo storico. Bologna: il Mulino.

Toso, F. 2006. “Quale senso ha oggi la ricerca dialettale?”. In F. Toso (ed.), Liguria linguistica. Dialettologia, storia della lingua e letteratura del Ponente. Saggi 1987-2005, pp. 274-286. Ventimiglia: Philobiblon.

Toso, F. 2009a. La letteratura ligure in genovese e nei dialetti locali. Profilo storico e antologia. Vol. I: Origini e Duecento. Genoa: Le Mani 2009.

Toso, F. 2009b. La letteratura ligure in genovese e nei dialetti locali. Profilo storico e antologia. Vol. VII: Il Novecento. Genoa: Le Mani 2009.

Varvaro, A. 2001. Linguistica romanza. Corso introduttivo. Naples: Liguori.