In late 2018, less than a year after historian of religion extraordinaire Jonathan Z. Smith had passed away, I submitted an abstract to an interesting conference organized by the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, entitled “When the Chips are Down,” It’s Time to Pick Them Up: Thinking With Jonathan Z. Smith. The aim of the conference was to “conside[r] theoretical and methodological issues central to J. Z. Smith’s oeuvre in the context of the [participants’] research.”

“Who’s J. Z. Smith?”, you might ask. Well, insofar as an introduction of Smith is needed, suffice it to recall here that his “contribution to the field of religious studies [is] immense” and that he was able to “move it […] in a new and better direction after Eliade” (Kessler 2012: 212; emphasis added).

Now, since Jonathan Z. Smith was among the main protagonists of my 2019 volume An Unnatural History of Religions, I was well acquainted with Smith’s cultural and intellectual biography. Not only that, but Smith was one of those very few scholars in the field whose writings allowed me to reconcile at long last my lifelong passion for palaeontology and evolutionary biology with my professional career in the history of religions. Smith’s works were thus instrumental in pointing me in the direction of a consilient paradigm between the natural sciences, the humanities, and the social sciences. And yet, in late 2018, what I saw in Smith’s works, and the way they inspired me to pursue alternative paths, seemed to continue to pass under the radar of most of my colleagues and friends, which I found – and I still find – quite baffling.

Here’s my original 298 words paper proposal:

An unsuccessful submission. Smh. Leonardo Ambasciano, late 2018.

Unfortunately, my abstract got rejected because the organisers received “proposals from more people than [they were] able to invite. As a result, many excellent proposals had to be turned down” (or so they wrote, which was totally fine by me). After receiving this news, I was under the dumps for a while, and I never got the chance – nor the will – to come back to my abstract. Then, the pandemic happened, and all hell broke loose. However, there was a lot of data and information in my 2019 book basically on the same exact topic. And it’s a pity that this lesser known side of J. Z. Smith never got the disciplinary attention I think it deserves.

Thus, today I’ve decided to post what I might have included in my speech should it have been accepted by pasting together and adapting some relevant excerpts from my book (more precisely, from Ambasciano 2019: 131-2; 169-70), with a few tweaks and the addition of some diagrams. Of course, this is not the speech I might have come up with, nor is it intended to provide a full account of Smith’s phylogenetic interests and/or of his influence on my own work. It’s just a post meant to illuminate a very interesting aspect that I tackled in my volume and that I think is still neglected by Religious Studies scholars. I hope you enjoy this post as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing it and I refer anyone interested in having the full picture and the whole historical context to my book.

Biographical notes

A remarkable interest in natural classification prompted Jonathan Z. Smith (1938–2017) to advocate the use of numerical taxonomy to overcome the limitations implicit in both phenomenology and morphology and to redefine in more epistemically warranted terms the historical relationships within and between religions.

Inspired by an ongoing interdisciplinary Marxist reconciliation with Kantian philosophy and Freudian psychoanalysis, impressed by German philosopher Ernst Cassirer’s (1874–1945) article “Structuralism in Modern Linguistics” (1945), and critical of the phenomenology of religion since his structuralist BA thesis entitled “A Prolegomenon to a General Phenomenology of Myth” (Haverford College, 1960), Smith earned his PhD at Yale Divinity School in 1969, discussing a dissertation on “The Glory, Jest and Riddle: James George Frazer and The Golden Bough” (Smith 2004: 3, 7, 29 n. 38). While working on his PhD project, Smith was employed first at Dartmouth College (1965–1966) and then at the University of Santa Barbara, California (1966– 1968), where he met Mircea Eliade for the first time when the Romanian scholar – at that time probably the world’s most famous scholar in the field – was serving as Visiting Professor, while Smith had just returned from an interview at the University of Chicago. In 1968, Smith became assistant professor at the Divinity School of Chicago, and later full professor from 1975 until his retirement in 2013, resigning from his Divinity school affiliation in 1977 (Smith 2004: 4–12).

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) on butterfly weed, a member of the milkweed family of flowering plants. Source: Martin La Bar, 2006 (CC BY-NC 2.0), Flickr.

“A deep interest in natural history”

Despite these humanistic interests, the methodological roots of Smith’s ideas were deeply embedded in the fertile humus of natural history. Since his youth, Smith had a keen interest in biology. His first scholarly paper publication was a quantitative study about the “average number of milkweed plants (Asclepias sp.) per acre, undertaken in support of the Royal Ontario Museum’s monarch butterfly migration project” (Smith 2004: 2). However, agrostology, the botanical study of grasses, was his first and foremost passion. “That”, he said in an interview in 2008, “was what I wanted to do with my life” (Sinhababu 2008). Intending to study agrostology at Cornell Agricultural School, Smith worked on a farm as a practical preparation for his future career. However, he eventually decided against enrolling at Cornell because of the impossibility of including liberal art courses in his curriculum (Sinhababu 2008). Anyway, as Smith himself recalled in 2004, “agrostology led [. . .] to a deep interest in natural history [which] remains today; taxonomic journals are the only biological field I still regularly read in” (Smith 2004: 2).

Comparison was the trait d’union between his botanical and taxonomic interests and religions:

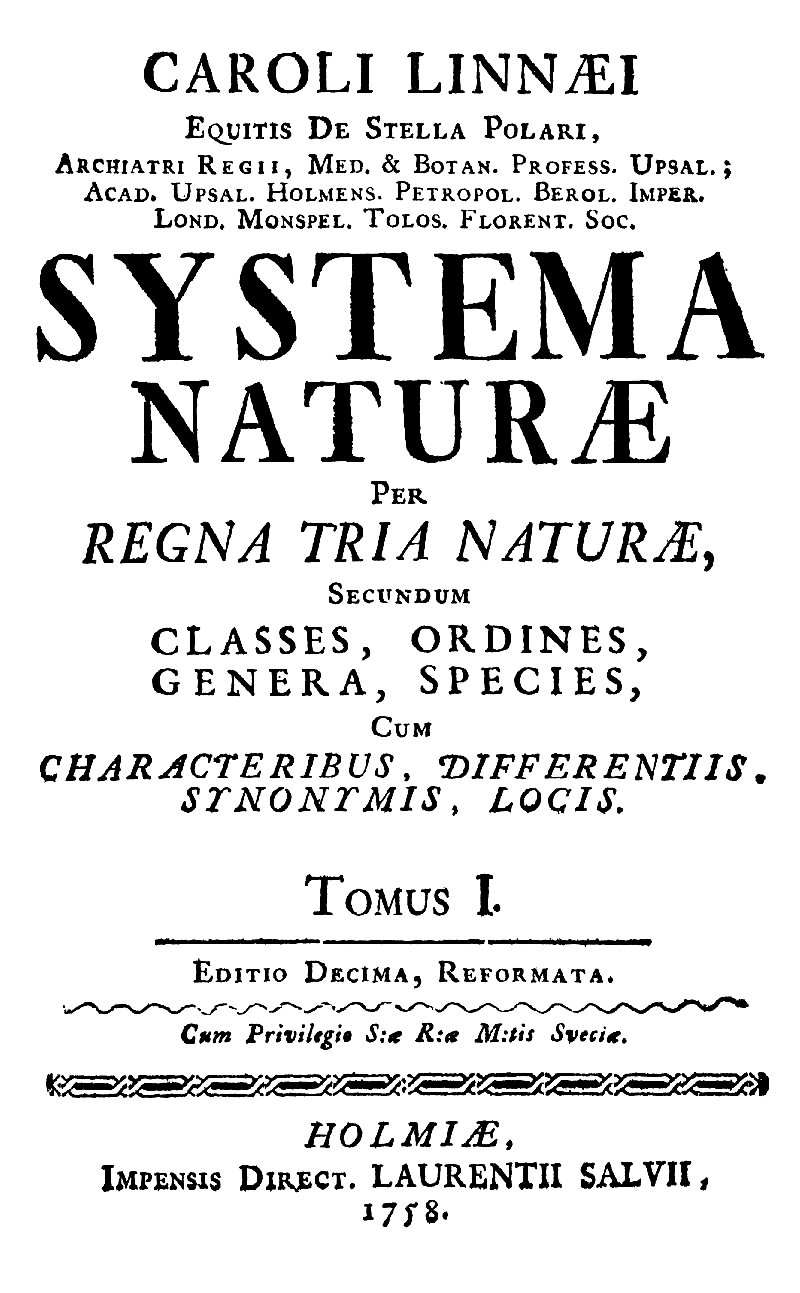

I think that’s what got me interested in grass – how many kinds of grass there are. I’m fascinated by how many kinds of religions there are, how many kinds of Bibles there are. Linnaeus gave us a way of talking about the diversity of grasses (Sinhababu 2008; cf. Smith 2004: 19).

However, the most important taxonomic influence for Smith’s subsequent theoretical works on religion was not Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae but modern quantitative taxonomic classifications which, starting from the 1960s, marked a paradigm shift in the biological sciences (Smith 2004: 22). The two major innovations in the field of taxonomic classification, at that time still stuck in an unresolved tension between progressive, evolutionary, Darwinian and static, non-evolutionary, Linnean concepts of taxa, were phenetics and cladistics, promptly acknowledged by Smith (1990: 47–8 n. 25; Smith 2000).

What is phenetics?

Phenetics, also known as numerical taxonomy, was a “phenomenological approach to systematics” in which classification renounced phylogeny (i.e. historical relationships) and focused on natural similarity in order to create a theory-free model and avoid preconceived ideas about ranking and clustering (Rieppel 2008: 296). In a word, phenetics avoided interpretation, which had been instead thought of by previous evolutionary systematists as the passe-partout to order and classify organisms (Stuessy 2009: 71). In particular, those evolutionary systematists weighed differently specific physiological features in order to correlate characters to heredity and change over time. However, lacking precise quantitative methods, those empirical classifications were prone to various biases, the most important of which was the limited amount of character coding. Phenetics represented a direct response to such a poor state of affairs as it took advantage of cutting-edge developments in computational power and computer programming to measure, code, calculate, and cluster a previously unmanageable amount of data (Hamilton and Wheeler 2008: 335). Once analysed, the resulting data matrices were clustered in “phenons”, i.e. new taxonomical groups, and graphically represented in “phenograms”, tree-like representations of similarities among taxa which put aside diachronic development.

How the “theory-free” numerical taxonomy of phenetics worked. Diagram © Leonardo Ambasciano, after Sokal and Sneath 1963: xviii (“phenons” are taxonomic groups of organisms established on the basis of their overall similarity).

Smith, influenced by ahistorical morphological approaches in the field of history of religions, focused on synchronic phenetics for the analysis of a historical case study (in Smith’s case, circumcision in early Judaism) (Smith 1982: 4, a paper originally delivered in 1978). In his article, Smith pleaded for the adoption of numerical taxonomy in the history of religions to cluster religious taxa within the same tradition according to a polythetic classification. However, as Benson Saler noted, there was no attempt to use phenetics practically in Smith’s essay, as this taxonomic approach was merely exploited as a tool with which to think (Saler 2000: 180). Limiting his foray into taxonomy as a preliminary theoretical effort, Smith recognized that it was “premature to suppose a proper polythetic classification of Judaism [although] it is possible to be clear about what it would entail” (Smith 1982: 8). And yet, subsequent research by Smith did indeed retreat from such a practical attempt to an increasingly theoretical corner, possibly because disillusioned by the increasing criticism faced by phenetics, especially by its main competitor and eventual defeater, cladistics, or phylogenetic systematics (Saler 2000: 180–96).

Trouble in phylogenetic paradise

Indeed, Smith’s phylogenetic model of choice soon showed its limitations. While pheneticists claimed that their model was objective, repeatable and testable, their approach relied on three a priori assumptions:

phenetic analysis was almost entirely methodologically dependent on “which mathematical tools one employs”, especially when there is “no objective, theory-free way to choose which algorithm to use” (Hamilton and Wheeler 2008: 335; cf. Ambasciano and Coleman 2019);

despite the presence of statistical tools, phenograms are synchronic accounts of affinity between taxa, without historical depth;

according to its opponents, phenetics suffered from a confirmationist approach incapable of discriminating between homologies and analogies, i.e. respectively, traits inherited from common descent or traits independently developed due to similar historical constraints (cf. Rieppel 2008; see Hull 1988).

As palaeontologist and historian of science Stephen J. Gould (1941-2002) summarised, the main problem is that, without historical data, “morphology is not the best source of data for unraveling history” (Gould 1986: 68). Morphology deceives: crocodiles are more closely related to birds than snakes; sharks, tunas, ichthyosaurs and dolphins share a superficially similar, hydrodynamic body plan because of convergent evolution in a similar environment but they are all distantly related (e.g., dolphins are more closely related to humans than to tunas); the panda is more closely related to bears than to the lesser panda; fungi are not “plants”, and so on.

Body plans do lie: this is NOT a natural group of phylogenetically strictly related animals! Composition: Leonardo Ambasciano (CC BY-SA 3.0). Silhouettes: clockwise, from upper left - Tuna (Thunnus alalunga): no copyright (by Felix Vaux), http://www.phylopic.org/image/c7b048bd-f2c0-4f46-a9b6-70da71a806c8/; shark (Carcharodon carcharias): no copyright (by Steven Traver), http://www.phylopic.org/image/545d45f0-0dd1-4cfd-aad6-2b835223ea0d/; ichthyosaur (Ichthyosaurus communis): no copyright, by Jagged Fang Designs, http://www.phylopic.org/image/8d7843dd-3f6d-476c-83ed-961610c4d1ef/; dolphin (Delphinus capensis): (CC BY-SA 3.0) by Chris huh, modified, http://www.phylopic.org/image/3caf4fbd-ca3a-48b4-925a-50fbe9acd887/.

A competing system, called cladistics, proved to be more resilient and epistemically warranted. Cladistics relied on:

differently weighted characters according to their historical states (i.e. derived, or more recent; primitive, or more ancient);

the acknowledgement that taxa branch and modify through time and space, being derived from a common ancestor;

the separation between homologies and analogies, with homologies further subdivided into synapomorphies, i.e. recent and informative, and symplesiomorphies, i.e. primitive and uninformative (Hennig 1966; cf. Saler 2000: 180–96).

finally, in a time when taxonomy was accused of bordering on pseudoscientific status, cladistics implemented a hypothetico-deductive falsificationism as its modus operandi, conferring renewed dignity to the sub-field (but cf. Rieppel 2008; on the history of taxonomy, see Hull 1988).

Phenogram (left) versus cladogram (right): fight! Even from such a schematic example, we can immediately appreciate the presence of historical relationships and changes over time in the cladogram on the right. From Mayr (1965): 81.

Today, cladistics has been quite successfully adopted to study cultural evolution (cf. Mesoudi 2011: 86–94). It is very likely that Smith’s passion for agrostology might have misled him in his attempt to transfer this particular taxonomic model to historiography and cultural studies, for phenetics has been able to resist for a long time within the niche of grass evolution and domestication while it failed to recover homological patterns in angiosperm variation and was substituted by cladistics elsewhere in natural sciences (Chapman 1992; Stuessy 2009: 72; for conflicting topologies in plant taxonomy, cf. Mishler 2000).

Visualising clades: a cladogram illustrating historical relationships of descent between extant primates. Common names in quotation marks on the right are used inappropriately to group together phylogenetically more distant primates (see, for instance, “prosimians” including tarsiers within Strepsirhini). Also, the different taxonomic units that include any given lower taxon constitute a sort of historically cumulative ID of the taxon in question, so that, for instance, going à rebours, bonobos, while still a member of subtribe Panini, are also members of the Hominini tribe, the Hominidae family, the Hominoidea superfamily, the Catarrhini parvorder, the Anthropoidea infraorder, etc. Credits: composition © Leonardo Ambasciano; silhouettes - Galago: Joseph Wolf, 1863 (vectorization by Dinah Challen) [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/7fb9bea8-e758-4986-afb2-95a2c3bf983d/; Loris: Mareike C. Janiak (CC BY-SA 1.0) http://phylopic.org/image/7f877a9e-53d7-48d0-a422-d3fa0ff5e2f9/; Lemur: Roberto Díaz Sibaja (CC BY-SA 3.0) http://phylopic.org/image/d6cfb28f-136e-4a20-a5ac-8eb353c7fc4a/; Tarsiidae: Yan Wong (CC BY-SA 3.0) http://phylopic.org/image/f598fb39-facf-43ea-a576-1861304b2fe4/; Ateles: Yan Wong [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/aceb287d-84cf-46f1-868c-4797c4ac54a8/; Papio: Owen Jones [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/72f2f854-f3cd-4666-887c-35d5c256ab0f/ Siamang: uncredited [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/0174801d-15a6-4668-bfe0-4c421fbe51e8/; Pongo: Gareth Monger (CC BY-SA 3.0) http://phylopic.org/image/63c557ce-d82c-42e6-a26a-a9f0f05c2c18/; Gorilla: T. Michael Keesey [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/d9af529d-e426-4c7a-922a-562d57a7872e/; Pan: Jonathan Lawley [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/7133ab33-cc79-4d7c-9656-48717359abb4/; Homo: NASA [No copyright] http://phylopic.org/image/a9f4ebd5-53d7-4de9-9e66-85ff6c2d513e/.

a good tool to think with?

In hindsight, grass was definitely not a good tool to think with insofar as culture and religion were concerned, and this might even be the main cause of the theoretical issues left unanswered by Smith (Strenski 2016). Notwithstanding such a setback, Smith’s interest in theoretical taxonomy, fuelled by his passion in natural sciences, led him to outshine most of his peers and colleagues, pave the way for future research in cross-disciplinary research, and leave a mark on the entire discipline – and beyond.

Refs.

Ambasciano, L. 2019. An Unnatural History of Religions: Academia, Post-truth and the Quest for Scientific Knowledge. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Ambasciano, L. and T. J. Coleman, III. 2019. “History as a Canceled Problem? Hilbert’s List, du Bois-Reymond’s Enigmas, and the Scientific Study of Religion.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 87(2): 366-400. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfz001

Chapman, G. P. (ed.) 1992. Grass Evolution and Domestication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hamilton, A. and Q. D. Wheeler. 2008. “Taxonomy and Why History of Science Matters for Science: A Case Study.” Isis 99(2): 331–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/588691

Hennig, W. 1966 [1950]. Philogenetic Systematics, trans. D. D. Davis and R. Zangerl. Urbana, Chicago and London: University of Illinois Press.

Hull, D. L. 1988. Science as a Process. An Evolutionary Account of the Social and Conceptual Development of Science. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Kessler, G. E. 2012. Fifty Key Thinkers on Religion. London and New York: Routledge.

Mesoudi, A. 2011. Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture & Synthesize the Social Science. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Mayr, E. 1965. “Numerical Phenetics and Taxonomic Theory.” Systematic Zoology 14(2): 73-97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2411730

Mishler, B. D. 2000. “Deep Phylogenetic Relationships among ‘Plants’ and Their Implications for Classification.” Taxon 49(4): 661–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/1223970

Rieppel, O. 2008. “Re-writing Popper’s Philosophy of Science for Systematics.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 30(3–4): 293–316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23334453

Saler, B. 2000 [1993]. Conceptualizing Religion: Immanent Anthropologists, Transcendent Natives, and Unbounded Categories. New York and Oxford: Berghan Books.

Sinhababu, S. 2008. ‘Full J. Z. Smith Interview.’ The Chicago Maroon, 2 June. https://www.chicagomaroon.com/2008/06/02/full-j-z-smith-interview/ (accessed 30 April 2022).

Smith, J. Z. 1982. Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Smith, J. Z. 1990. Drudgery Divine: On the Comparison of Early Christianities and the Religions of Late Antiquity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Smith, J. Z. 2000. “Classification.” In W. Braun and R. T. McCutcheon (eds), Guide to the Study of Religions, 35–44. London and New York: Cassell.

Smith, J. Z. 2004. Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Strenski, I. 2016. ‘The Magic and Drudgery in J. Z. Smith’s Theory of Comparison.’ In P. Antes, A. W. Geertz and M. Rothstein (eds), Contemporary Views on Comparative Religion: In Celebration of Tim Jensen’s 65th Birthday, 7–16. Sheffield and Bristol, CT: Equinox.

Stuessy, T. F. 2009. “Paradigms in Biological Classification (1707–2007): Has Anything Really Changed?” Taxon 58(1): 68–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27756825