Walt Disney is said to have pinned a note over each of his animators’ desks: “Keep it cute!”

Deirdre Barrett (2010): 69

It all began with a mouse

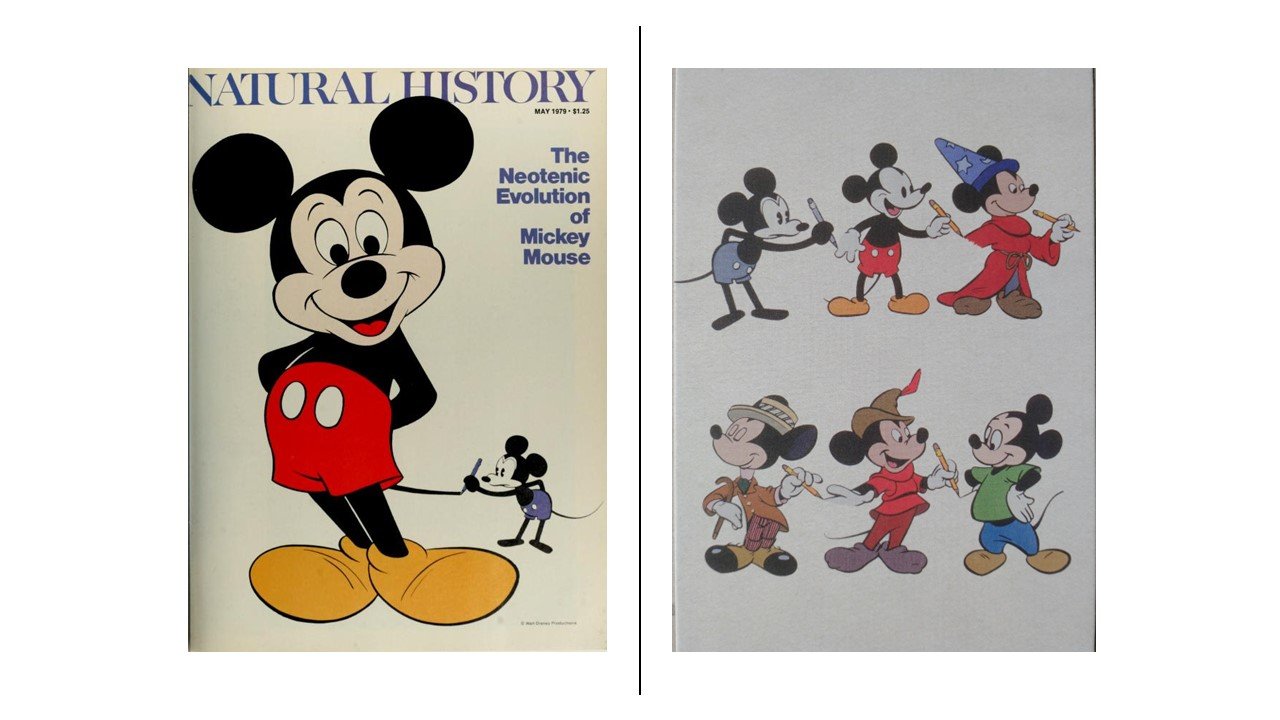

In 1979, palaeontologist and historian of science extraordinaire Stephen J. Gould (1941-2002) published what might be considered one of the most eclectic and thought-provoking analysis ever dedicated to Mickey Mouse (Gould 1980). Gould’s pioneering and interdisciplinary foray into pop culture, re-titled “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse” in 1980 [1] and originally written in occasion of Mickey Mouse’s 50th anniversary, examined Walt Disney & Ub Iwerks’ icon both as a cultural artefact and a most peculiar biological organism. Inspired by the work of ethologist Konrad Lorenz, Gould identified a directly proportional relationship between the modification of Mickey Mouse’s behaviour, which in his first appearance in the cartoon “Steamboat Willie” (1928) was “rambunctious, even slightly sadistic” (not to mention his patently sexual relationship with Minnie), and the fictitious mouse’s tendency to accumulate ever more “babyish features” in its body as time went by (Gould 1980: 81, 86).

Ever the keen naturalist, Gould collected the data from three Mickey Mouse specimens (dating from the early 1930s, 1947, and 1977), as if they were specimens from an evolutionary sequence of a single taxon, to quantify “Mickey’s creeping juvenility” according to three parameters: “increasing eye size […] as a percentage of head length […]; increasing head length as a percentage of body length; and increasing cranial vault size measured by rearward displacement of the front ear” (Gould 1980: 84). The end results were staggering: “eye size increased from 27 to 42% of head length; head length from 42.7 to 48.1 of body length; and nose to front ear from 71.7 to a whopping 95.6% of nose to rear ear” (Gould 1980: 84) [Fig. 2]. Remarkably, the adult Mickey Mouse’s face and body were becoming more similar to those of his young nephew Morty.

Fig. 2. Left: the cover of Natural History from May 1979. Source: The Disney resource index (DIX); right: “Mickey Mouse Meets Konrad Lorenz” (1979), 2019 postcard from Mickey Mouse Museum reproducing the same image used by Stephen J. Gould in his Natural History article. Gould’s sample of the three stages in Mickey Mouse's development consisted of the middle figure in the top row plus the middle figure and the first figure from the right in the bottom row. Personal collection. © Disney Enterprises, Inc.

Cute overload

In evolutionary biology, this process of progressive juvenilisation is called neoteny. In technical terms, a neotenic taxon goes through a heterochronic alteration of its developmental process through paedomorphosis, reaching sexual maturity without displaying certain expected morphological changes. In layman’s terms, adult neotenic organisms retain some of the typical juvenile features possessed by their evolutionary forebears during youth. Textbook examples of neoteny are: the axolotl salamander, in which the juvenile gills are retained throughout adulthood; the skull of birds, which displays the typical juvenile features of their non-avian dinosaur ancestors (e.g., bigger eye sockets, shorter snouts); and the slowing down of the growth processes in Homo sapiens, which led to longer pregnancy, longer childhood, less ontogenetic facial changes in adulthood relative to other apes, and lifelong childlike curiosity and nonstop learning (see, resp., Signorile 2012: 141-145; Gould 2003; Long and MacNamara 1997 and Bhullar et al. 2012). The most striking bit about Gould’s “very entertaining” essay about cultural evolution in pop culture (Berkow 2006: 154) is that we have an animal – Homo sapiens – able to identify its own neotenous cognitive bias which, in turn, is commercially weaponised in most ingenious ways. As evolutionary psychologist Deirdre Barrett quipped, “as he got physically cuter, Mickey became sweeter and less aggressive – and Disney grew richer” (Barrett 2010: 69).

Gould’s argument in his 1979 essay was that the artists and the animators working with Disney, as well as their market research colleagues that were investigating the features able to make an intellectual property cuter and therefore more sellable, “unconscious[ly] discover[ed]” the “biological principle” behind the affection and attachment elicited in adult human beings by the presence of certain distinct features that characterise childhood, such as “large eyes, bulging craniums, retreating chins” (Gould 1980: 88-89). Biologist Lisa Signorile has labelled the ethological response that makes us go Aww! That’s cute! (while eliciting at the same time our preference for those organisms that exhibit specifically neotenic features) the “Bambi effect” after the protagonist of the eponymous 1942 Disney animated movie – which, interestingly, was itself an infantilized, toned-down version of Felix Salten’s original and much darker novel (Ferguson 2021; see Signorile 2009). We innately tend to display affection and feel more protective in front of the “disarming tenderness” and powerlessness of young organisms that exhibit such features, regardless of their human or nonhuman status: “we are fooled by an evolved response to our own babies, and we transfer our reaction to the same set of features in other animals” (Gould 1980: 86, 87). Conversely, four-year-olds and younger toddlers tend to prefer toys with more adult features, which makes perfect evolutionary sense: attachment towards parents or care figures who exhibits adult facial features boosts survival (Morris, Reddy and Bunting 1995; cf. Barrett 2010: 70). The main target of the cultural evolution behind any pop-culture juvenilisation is adult – or at least adolescent – buyers.

This exploitation of our innate behaviours and evolved feelings for market purposes is not new: Nobel prize laureate Konrad Lorenz, whose pioneering ethological observations inspired Gould’s essay, had already noted the “trend for dolls to get progressively cuter – first they looked like people, then like children, then like supernormal exaggerations of children” (Barrett 2010: 69). The same happened with the cultural evolution of the facial features of the teddy bear over the course of the 20th century, with ever more pronounced “larger forehead and shorter snout relative to the dimensions of the head as a whole” (Hinde and Barden 1985: 1371). Today, kawaii pop culture phenomena and adorable Baby Yoda are just more of the same [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3. Left: the star of The Mandalorian TV series: Grogu, a.k.a. “Baby Yoda”. © LucasFilm, 2019. Source: Wikipedia; right: Bambi (left), Flower (middle), and Thumper (right) – three characters with exaggeratedly cute facial features, from the theatrical trailer for Bambi (1942). © Disney. Source: Wikipedia.

Along came a spider

Enticed by Gould’s observations, I decided to have some fun and check whether this neotenous bias in pop culture applied elsewhere. Gould chose the 50th anniversary of a veritable U.S. “national symbol” (Gould 1980: 86). I went for another national treasure: Spider-Man and his 50th anniversary in 2012. Originally created in 1962 by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko in “easily one of the best origin stories in the history of comic books, all in 11 compact pages” (Thomas 2020: 33), Spider-Man is probably the most famous comic book hero of the Silver Age of comics and an all-time, multimedia Marvel Comics juggernaut. At his most basics, Spider-Man’s story is a “bildungsroman, the story of how a youth becomes an adult […] it’s ‘the Itsy-Bitsy Spider.’ Peter [Parker] is not yet – never yet – the person he needs to become” (Wolk 2021: 80).

Fig. 4. Jack Kirby’s cover for Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962). Metal poster art, personal collection. Marvel Legends #1 (2018). © Marvel

The first Spider-Man story appeared on the 15th issue of an anthology series called Amazing Adult Fantasy (for the occasion renamed just Amazing Fantasy [Fig. 4]) and featured a shy, bullied Midtown High School nerd student, fifteen-year-old Peter Parker, who is accidentally bitten by a radioactive spider during a science exhibit. As a result of this incident, young Parker gains the proportional strength, agility, and wall-climbing ability of a spider plus, as revealed later on, a precog ability called “spider sense.” Parker, an orphan who lives with his beloved aunt and uncle in financial distress, tries immediately to capitalize on his newly acquired superpowers by becoming a costumed wrestler and a TV sensation. But pride comes before the fall: a thief runs past him in the studio but Parker, now overconfident to the point of being arrogant in his costumed persona, sees no reason to care and to stop him. Once home, Parker faces the terrifying news that a burglar shot dead his beloved uncle. As Spider-Man, Parker manages to catch the burglar turned assassin only to discover that that’s the same felon he could have easily stopped in the studio, thus preventing the death of his uncle. The lesson from Lee and Ditko is clear: “from a great power there must also come -- great responsibility!”. A humbled Parker, annihilated by guilt and remorse, decides thus to atone by devoting his life and his newly acquired superpowers to helping others in his new, dedicated comic book series, The Amazing Spider-Man (March 1963-ongoing).

Lee and Ditko’s experiment “strayed far from superhero conventions” (Howe 2012; cf. with Eco 2012 and McFarland Coogan and Rosenberg 2013: 54) and was so successful that its publication marked what might be labelled as a paradigm shift in superhero comic book literature. First, “this wasn’t the world of moon rockets, flying cars, giant monsters, or chisel-jawed heroes – it seemed this could happen to any kid” (David 2020: 32). Second, the mix of ordinary problems, real world setting, a bullied but brilliant teenage protagonist, constant money problems, soap opera-like romance, and extraordinary superpowers proved irresistible: “here was a character who, unlike perfect heroes of the Superman type, was just a regular guy with regular problems – like me and everyone else” (David Michelinie in Singer 2019: 14).

What big eyes you have!

In 2012, struck by the changes that affected the superhero’s mask, I thought that Spider-Man was probably undergoing a progressive juvenilisation not unlike the one that affected Mickey Mouse. The following year, following in Gould’s footsteps, I finally decided to collect a representative sample of twenty-two Spider-Man masks from 1963 to 2011 to “give my observations the cachet of quantitative science” (Gould 1980: 84; see Fig. 1; the list is available in the Appendix below). However, because of practical reasons and previous commitments, I had to limit my analysis to Gould’s first parameter, i.e., eye size increase as a percentage of head length. Just like Gould, I considered the ratio between the white lenses of those Spider-Man’s masks (his white “eyes” or pupils) and the length of his head as if I was studying a phylogenetic sequence of a single taxon [2]. I also decided to include four recent specimens from Ultimate Spider-Man, a comic books series first published in 2000 with the explicit aim to relaunch the character with a high school blank slate after forty years of cumbersome comic continuity in which Peter Parker went to college, married, and had a child [3]. Ultimate Spider-Man was published from 2000 to 2011 alongside the other books dedicated to Spider-Man where readers could read the ongoing adult adventures of Peter Parker/Spider-Man, the explanation being that the two were Peter Parkers from different realities within the Marvel multiverse, the young and Ultimate one living on Earth-1610, the older version existing on Earth-616.

Fig. 5. Correlation between year and ratio (ρ=0.72, p<0.0001). Graphic design and data elaboration by Andrea Cau.

The preliminary results from all specimens [Fig. 5] confirmed the presence of an ongoing paedomorphic process with a whopping 325% increase in eye size. Even sticking to the Earth-616 specimens, and thus excluding the four younger Ultimate Spider-Man entries, between 1963 and 1997 the eye size increase was an astonishing 275%. The youth tend to have bigger eyes relative to the length of the head than the adults of the same species. My cultural evolutionary sample confirms this principle: the “adult” Earth-616 specimens’ average increase of the “eyes”/head length ratio through time was 25.6%, while the increase of the same measure in the younger Ultimate specimens from Earth-1610 was 48.5%. The same seemingly apply to the Spider-Men featured in other media franchises [Fig. 6].

Remarkably, except for certain “darker” storylines or periods, Spider-Man’s trademark behaviour is generally presented in the whole Marvel multiverse as playful, even frivolous, and characterised by childish reactions and witty quips, which are sometimes taken to the extreme depending on the writers’ sensibilities. This only adds to the neotenous character of Spider-Man.

Fig. 6. DVD covers of two Spider-Man animated series. Notice the striking neotenous features of The Spectacular Spider-Man (first aired in 2008; on the right) compared to the more adult attributes of Spider-Man: The Animated Series (first aired in 1994; on the left). Personal collection.

A life in pictures

I was also able to pinpoint the cultural evolutionary event that, both in emic and etic terms, marked this transition to ever bigger eyes in the history of the Spider-man taxon. During the 1984-1985 comic book crossover Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars by Jim Shooter, Mike Zeck, and Bob Layton, Spider-Man was transported to a distant galaxy where his classic red-and-blue costume had to be replaced by a black and white costume, later revealed to be an alien symbiote. In commercial terms, that seminal crossover was dictated by a corporate decision to accompany and boost the launch of a new Mattel toy line dedicated to Marvel superheroes [4]. In evolutionary terms, the (temporary) relocation of Spider-Man elsewhere in outer space represents the ultimate peripheral isolate at the margins of the Spider-Man taxon’s “natural” environmental range– nothing is more isolated than a planet in a different galaxy! Metaphorically speaking, what happened on that fictitious planet was something akin to a “rapid and episodic event of speciation” (Gould and Eldredge 1972: 84) in that that Spider-Man became the founder of a distinct and wildly successful population, to the point that even after the superhero came back to his traditional red-and-blue costume on his Earth-616, the lenses or “eyes” to head length ratio of the mask was forever altered.

For instance, when Silver Age maestro John Romita Sr. came back to illustrate a Spider-Man story in 1997, the proportions of his Spider-Man mask were not the ones he himself had depicted in 1968 – when his portrait of the superhero was de facto the definitive Spider-Man corporate look – but were more in line with the new “population” measures (cf., resp., nos. 18 and 3 in Fig. 1). You can appreciate the impact of the Secret Wars events by looking at the tenth square from the left in Fig. 5: that’s Spider-Man famous black costume, rather infamously featured on the silver screen in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 3 (2007) and whose mask takes centre stage in Figure 1 as no. 10.

Cute Spiders

I know that invoking neoteny to make sense of the aesthetic changes in the Spider-Man’s masks might seem too far fetched. Not only it’s an inanimate object but it’s also one that’s supposed to symbolise stylistically an organisms as far removed from the usual animals whose distinct facial features makes us go Aww! as anyone can possibly conceive. However, the Bambi effect is a cognitive bias that can be triggered by visual cues no matter how basic, provided that certain conditions are met. Cognitive dispositions like the one behind the Bambi effect are only good enough and imperfect programs, and as such they can be easily hijacked by triggers (or stimuli) that fall outside what cognitive psychologist and social scientist Dan Sperber calls their “proper” evolutionary domain (see McCauley 2011: 157). The fact that we feel more protective towards toddlers when we recognise certain facial features is an adaptive disposition because it increases our fitness as a taxon by prompting a caretaking behaviour through neurochemical mediation. But we also feel more or less the same when presented other visual cues that meet the same basic conditions, and that’s a “latent susceptibility” of that disposition that has no direct evolutionary advantage and which can be culturally exploited to make fictional characters more appealing (McCauley 2011: 157) [5].

Indeed, the Bambi effect is so powerful that, with enough tweaks, it can make more likeable animals which human beings strongly dislike or find abhorrent as a result of an evolutionarily selected precautionary response (Hoehl et al. 2017). Spiders are as good an example as anything. Getty Images has an entire virtual shelf of “cute spider” images, and a video animation of a jumping spider with gentle facial features and huge, neotenic eyes, called “Lucas the Spider”, reached over 35 million views since it was first posted on YouTube four years ago, spawning a Cartoon Network animated series in 2021! [Fig. 7]

Fig. 7. Left: Getty Images search, “cute spider” screenshot. Right: Lucas the Spider. Source: Wikipedia.

Competing variants

According to Norman MacLeod, images

“are both the products of the instruction set and the vehicles in which the instruction set stores itself. Different instruction sets use this vehicle to move about in the environment (= human culture), enter into a direct interaction with that environment, and compete with each other for the resources necessary to complete their purpose: replication” (MacLeod 2009: 206).

In a sense, cultural and artistic competition between iconographic variants was ultimately decided by the public acting as the main environmental constraint towards the end of the past century: the Spider-Man images with bigger eyes were the more successful and thus spread epidemiologically and exponentially in the comic book pages first, and then on the cinema and TV screens of the entire world with multiple films and animated series. I wonder which peripheral isolates coming from currently unimaginable and wondrous future storylines will be most successful in spreading their copies in the next fifty years of Spider-Man – better yet, the Spider-Men of the various Marvel multimedia multiverses. Stick around for the 100th anniversary to find out!

Appendix

Legend: A = Artist; ASM = The Amazing Spider-Man; SSM = Spectacular Spider-Man (including Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man); SM = Spider-Man; WSM = Web of Spider-Man; USM = Ultimate Spider-Man; UCSM = Ultimate Comics Spider-Man

Sources for Figs. 1 and 5:

“Spider-Man”, ASM #1, Mar. 1963. A: Steve Ditko

“The Molten Man regrets...!”, ASM #35, Apr. 1966. A: Steve Ditko

“Goblin Lives!”, SSM 2, Nov. 1968. A: John Romita Sr.

“The Punisher strikes twice!”, ASM #129, Feb. 1974. A: Ross Andru

“Ashes to Ashes”, SSM #28, marzo 1979. A: Frank Miller

“The Spider and the Burglar... A Sequel”, ASM #200, Jan. 1980. A: Jim Mooney

“Look Out There’s a Monster Coming!”, ASM #235, Dec. 1982. A: John Romita Jr.

“Mistaken Identities”, SSM #87, Feb. 1984. A: Al Milgrom

“Homecoming”, ASM #252, May 1984. A: Ron Frenz

SSM #107 cover, Oct. 1985. A: Rich Buckler

“Mysteries of the Dead”, ASM #311. A: Todd McFarlane

“Slugfest”, SM #15, feb. 1992. A: Erik Larsen

ASM #382 cover, Oct. 1993. A: Mark Bagley

“Time Is on No Side”, SSM #216, Sept. 1993. A: Sal Buscema

“Pursuit. Part One: The Dream Before”, SM #45, Apr. 1994. A: Tom Lyle

“Shadow Rising”, WSM #117, Oct. 1994. A: Steve Butler

“Funeral for an Octopus” #3 cover, May 1995. A: Ron Lim

“Spider-Man/Kingpin: To the Death”, Nov. 1997. A: John Romita Sr.

“Life Lessons”, USM #5, Apr. 2001. A: M. Bagley

UCSM #3 cover, Dec. 2008. A: David Lafuente

“Ultimatum. Part 4”, USM #132, July 2009. A: Stuart Immonen

USM #153 variant cover, Apr. 2011. A: Sara Pichelli

Notes

This post presents an updated and revised version of a brief essay originally written in Italian and published as “Omaggio di uno storico all’Uomo Ragno” on 18 April 2013 on my former personal blog Tempi Profondi. Just like I did nine years ago, I thank once again Andrea Cau for his precious help.

[1] The article, originally entitled “Mickey Mouse Meets Konrad Lorenz”, is best known in its reprinted version as a chapter in Gould’s famous collection of essays entitled The Panda’s Thumb and published the following year (Gould 1980).

[2] This was the second reboot of the character after the unsuccessful modern relaunch by John Byrne with his Spider-Man: Chapter One (December 1998).

[3] Alternatively, we can also imagine the Spider-Man original image per se as the genotype and its cultural representations or pictures in the comics published after its debut as phenotypes (MacLeod 2009: 189).

[4] While we could easily envisage an immediate attempt at trying to reap the rewards of the Bambi effect, the idea for a Spider-Man black costume was actually first pitched by student Randy Schueller. Marvel liked and bought Schueller’s idea for later use (Singer 2019: 60).

[5] The indirect beneficiaries would be those Homo sapiens individuals able to capitalise intra-specifically on the Bambi effect through mass media and pop culture, that is, by making money thanks to the commodification of cuteness, thus potentially increasing their fitness through their higher disposable income and financial assets.

Refs.

Barrett, Deirdre. 2010. Supernatural Stimuli: How Primal Urges Overran their Evolutionary Purposes. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Berkow, Jerome H. 2006. Missing the Revolution: Darwinism for Social Scientists. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S., Jesús Marugán-Lobó, Fernando Racimo, Gabe S. Bever, Timothy B. Rowe, Mark A. Norell and Arhat Abzhanov (2012). “Birds Have Paedomorphic Dinosaur Skulls.” Nature 487(7406): 223–226. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11146

David, Peter. 2020. “Amazing Fantasy #15 – August 1962.” In Melanie Scott and Stephen Wiacek (eds.), Marvel Greatest Comics: 100 Comics that Built a Universe, 30-33. London: DK, a Division of Penguin Random House.

Eco, Umberto. 2004. “The Myth of Superman.” In Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester (eds.), Arguing Comics: Literary Masters on a Popular Medium, 146-164. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. Originally published in 1962 as “Il mito di Superman e la dissoluzione del tempo”, in E. Castelli (ed.), Demitizzazione e immagine. Padua: Cedam; reprinted in 1964 as “Il mito di Superman” in Apocalittici e integrati. Milan: Bompiani. Translated in English in 1972 by Natalie Chilton for Diacritics 2(1): 14-22. https://doi.org/10.2307/464920

Eldredge, Niles and Stephen J. Gould. 1972. “Punctuated Equilibria: An Alternative to Phyletic Gradualism.” In Thomas J.M. Schopf (ed.), Models in Paleobiology, 82-115. San Francisco: Freeman, Cooper & Co.

Ferguson, Donna. 2021. “Bambi: Cute, Lovable, Vulnerable ... or a Dark Parable of Antisemitic Terror?” The Guardian, 25 December. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/dec/25/bambi-cute-lovable-vulnerable-or-a-dark-parable-of-antisemitic-terror [Last accessed 10 May 2022].

Gould, Stephen J. 1980. “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse”, in The Panda’s Thumb, New York: W.W. Norton, pp. 125-133. Originally published in 1979 as “Mickey Mouse Meets Konrad Lorenz.” Natural History 88(5): 30-36.

Gould, Stephen J. 2003. Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Originally published in 1977.

Hinde, Robert A. and L. A. Barden. 1985. “The Evolution of the Teddy Bear.” Animal Behaviour 33(4): 1371-1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80205-0

Hoehl, Stefanie, Kahl Hellmer, Maria Johansson and Gustaf Gredebäck. 2017. “Itsy Bitsy Spider…: Infants React with Increased Arousal to Spiders and Snakes.” Frontiers in Psychology 8:1710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01710

Howe, Sean. 2012. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York: HarperCollins.

Long, John A. and Kenneth J. MacNamara. 1997. “Heterochrony.” In Philip J. Currie and Kevin Padian (eds.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego and London: Academic Press, 311-317.

MacFarland Coogan, Peter and Robin S. Rosenberg (eds.). 2013. What Is a Superhero? New York: Oxford University Press.

MacLeod, Norman. 2009. “Images, Totems, Types and Memes: Perspectives on an Iconological Mimetics.” Culture, Theory and Critique 50(2-3): 185-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14735780903240125

McCauley, Robert N. 2011. Why Religion Is Natural and Science Is Not. Oxford and New York: Oxford University PRess.

Morris, P. H., V. Reddy and R. C. Bunting. 1995. “The Survival of the Cutest: Who’s Responsible for the Evolution of the Teddy Bear?” Animal Behaviour 50(6): 1697-1700. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-3472(95)80022-0

Signorile, Lisa. 2009. “L’effetto Bambi”. L’orologiaio miope, 30 June 2009. http://www.lorologiaiomiope.com/leffetto-bambi/ [Last accessed 10 May 2022]

Signorile, Lisa. 2012. L’orologiaio miope. Turin: Codice edizioni.

Singer, Matt 2019. Spider-Man: From Amazing to Spectacular. The Definitive Comic Art Collection. San Rafael, CA: Insight Editions.

Thomas, Roy. 2020. The Marvel Age of Comics: 1961-1978. Köln: Taschen.

Wolk, Douglas. 2021. All of the Marvels: A Journey to the Ends of the Biggest Story Ever Told. New York: Penguin.