Prologue: when “shit-green” dinosaurs ruled the Earth

When a graduate student of Stephen Jay Gould went to the movies to watch Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster tentpole Jurassic Park in 1993, he lamented that the animals depicted in the movie – in particular the Velociraptor, called raptors – were “the same old, ordinary, dinosaur shit-green” (Gould 1996: 230). Gould reported his student’s colourful impressions in a studious review of the movie, where he duly noted that Spielberg tried to experiment “in early plans and models” with the “bright colors” you would expect in a birdlike animal evolutionarily closer to birds than lizards and other reptiles. However, in the end the production team decided to revert to dull, dated, and monochromatic reptilian hues (Gould 1996: 230). They had already renounced the hissing serpent-like tongue for the raptors featured in the first shooting tests for the kitchen attack sequence – and that was quite enough, thank you very much [1].

As snakes ranked among the top predators of early primates, thus exerting a potential evolutionary pressure on our ancestors (Isbell 2006; Isbell 2009), most of us are innately afraid of reptiles and snakes. It is too good a phobia not to be exploited by a director eager to evoke powerful feelings in the audience. In this sense, bird-like colours would not have been perceived as cinematically scary as the dull – but effective – “shit-green” reptile hues (Switek 2013: 139) [2]. The same happened with other artistic licences affecting the meat-eating dinosaurs depicted in the movie: no avian tegument, lizard skin, neck frills, altered shapes and dimensions, mammalian lips and smirks, weird ophthalmological inferences (“Don’t move! He can’t see you, if you don’t move”, says self-confident screen palaeontologist Alan Grant to teenager dinophile Tim Murphy in front of a Tyrannosaurus rex; cf. DeSalle and Lindley 1997) and, last but not least, outdated hand postures to make the raptors able to open doors. Spielberg bent reality as he saw fit to accommodate the screenplay penned by acclaimed writer and author of the original Jurassic Park novel Michael Crichton with David Koepp while exploiting the new image of dinosaurs coming from the so-called Dinosaur Renaissance, the palaeontological movement that, starting in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, worked hard to update the sorely stereotypical image of dinosaurs as swamp-loving, sluggish behemoths “destined for extinction” (Naish 2021: 55-57).

Now, if we want to play the devil’s advocate in favour of Spielberg’s choices for a moment, in the early 1990s there was only a handful of relatively well-known and charismatic animals to be used in the movie – most of them known for quite a long time (for instance, the T. rex holotype had been described way back in 1905). Additionally, the widespread presence of feathers and other bird-like features in dinosaurs was still theoretical (even though supported by robust circumstantial evidence, sound inferences, and a progressive research programme; cf. Havstad and Smith 2019), and conclusive soft-tissue evidence for the strikingly avian aspect of theropod dinosaurs was yet to be discovered. Despite the fact that illustrations depicting feathered dinosaurs were becoming increasingly common not just in scientific popularisation but also in pop culture, a mix of outdated reptilian outlook and dramatic surprises were thought important to play with the audience’s expectations.

Feathered dinosaurs in pre-Jurassic Park pop culture: a sample. Clockwise, from top left: Syntarsus (top left) and Avimimus (top right), “Dino-Swap” card game. Source: private collection. ©1992 Orbis Publishing; Struthiomimus action figure (bottom right, modified) and toy box artwork (bottom left). Dino-Riders toyline. © 1988 Tyco. Source: Dinoridersworld.com

The overwhelming response from the audience proved Spielberg’s intuition right: Jurassic Park became a Capital-P phenomenon – the highest grossing film ever released at the time (and today still in the Top 20 Lifetime Grosses adjusted for inflation) – and for a while dinomania ruled the entire world. Cinematic dinosaurs came of age and were finally promoted from supporting monsters in B movies to main characters in blockbuster tentpoles with consistent, if exaggerated, animal behaviours and sufficiently convincing cognitive processes. Even more importantly, cinematic dinosaurs found themselves under the meta-reflective spotlight of a wider discussion about the relationship between corporate powers, showbusiness, de-extinction, and science (Baird 1998; Cau 2015). All this wouldn’t have been possible without the ground-breaking digital and practical special effects featured in the movie, courtesy of Industrial Light & Magic and the Oscar-winning teams led by master craftsmen Dennis Muren, Stan Winston, Phil Tippett and Michael Lantieri. To cut a long story short, Jurassic Park was a cinematic milestone, and everything could be excused – even dull, “shit green”-coloured dinosaurs.

Coming to terms with hair loss

In 2004, palaeontologist Robert T. Bakker, one of the consultants for Spielberg’s original movie and the originator of the Dinosaur Renaissance moniker, lamented the unjustifiable addition of a “roadrunner’s toupee” over the heads of the newly coloured raptors presented by filmmaker Joe Johnston in the final episode of the loosely connected original Jurassic Park trilogy (Jurassic Park III, 2001). By then, completely feathered dinosaur fossils have been known in the scientific literature for about eight years. However, Bakker was reasonable enough to give the production crew the benefit of the doubt: he knew how difficult it was for CGI artists to digitally render a convincing plumage with the hardware available at that time and preconised that, with technological progress continuing apace, a hypothetical fourth episode of the Jurassic saga would have finally done feathered dinosaurs justice (Bakker 2004: 1).

Bakker’s prediction proved sorely incorrect. In 2013 a laconic message on Twitter by newly hired director Colin Tevorrow, now at the helm of a soft reboot/sequel of the franchise, announced on Twitter that his forthcoming movie – entitled Jurassic World and due to debut two years later – would not feature feathered dinosaurs:

In a reply dated 10 June 2013, Trevorrow also promised to deliver “both science and fiction”. Source: Twitter.

Trevorrow chose to maintain the dinosaurs’ body plan as close as possible to its 1993 appearance, warts and all, disavowing Johnston’s minimal innovations and sanctioning at the same time a revival of “the same old, ordinary, dinosaur shit-green” (Daly 2014) [3]. However, as noted by many palaeontologists, the absence of plumage was only the tip of an enormous iceberg of problems and mistakes related to the animals’ anatomy, only in part inherited from the first film (e.g., Switek 2014; Conway 2014; St. Fleur 2015; Naish 2021: 84).

Hyperreal dinosaurs

By putting the external appearance of the movie dino-stars above the need for a thorough scientific update, Trevorrow de facto endorsed the meta-ambiguity of a prehistoric zoo specifically opened to showcase animals perceived by the public as real, when in fact the park was populated by everything but real animals. This paradox was cunningly explained in the movie itself by returning geneticist Henry Wu (played by BD Wong). In a key scene where Wu has a discussion with Simon Masrani, the owner of the new prehistoric park, the geneticist paraphrases something Crichton came up with in the very first novel of the saga: in the park nothing has ever been “real”, because everything had been designed to be consumed and spectacularised in spite of reality. However, if in the 1991 novel the aim of genetic tampering was to have tamer and docile animals, here the goal is to go full “red in tooth and claw”. In the doctor’s own words:

“Nothing in Jurassic World is natural. We have always filled gaps in the genome with the DNA of other animals. And if the genetic code was pure, many of them would look quite different. But you didn’t ask for reality, you asked for more teeth” (Dr. Henry Wu, Jurassic World, 2015)

According to Brandon Kempner, this modus operandi exemplifies the paradox of the hyperreal, a concept elaborated by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) and embodied with astounding accuracy by the dinosaurs of the multimedia Jurassic Park franchise. According to Kempner,

“[…] Crichton gives us animals that never existed. To put this in the terms of Baudrillard: the scaly raptors is an example of the hyperreal. It is nothing more than an image, an invention of human beings. Despite Crichton’s best intentions, he created something absolutely unreal. What else could he do, though? Short of actually going back 65 million years, we’ll have to content ourselves with inventive and inaccurate recreations of dinosaurs. The crisis, though, lies in how we believe in those images. What do people actually love, dinosaur reality – fossils – or spectacular images? I think the answer’s pretty clear: we love the images.” (Kempner 2014: 116; see Baudrillard 1995) [4]

There is a fine moment in Jurassic World where the nonstop CGI spectacle leaves enough room for a thought-provoking, if fleeting, hyperreal and metanarrative reflection on the relationship between (A) the presence of a postmodern theme park based on a bigger-than-life corporate simulation of prehistoric life, and (B) the explosion of a social media environment dominated by selfies and instagrammable moments soon to be forgotten. The scene involves an enormous mosasaur devouring a great white shark à la Sea World while an entire amphitheatre of people take photos with their smartphones (and no, mosasaurs were not dinosaurs, they were not kaiju-size animals, and they were entirely aquatic; according to the in-universe explanation for recreating extinct animals, their presence here begs the question of how they were recreated).

Instagramozoic. Jurassic World Official Trailer, 25 November 2014.© Universal Studios and Amblin Entertainment, Inc. Source: YouTube.

As unbelievable as it may seem, this jaw-dropping attraction is not enough to keep the park economically afloat. In the in-universe fiction portrayed by the movie the park has been operating for almost ten years and, at this point, the prehistoric attractions seem on the verge to lose their “WOW!” factor. The powers that be behind the management of the prehistoric park know the economic dangers of habituation. To escape them, as anticipated by the aforementioned discussion between Wu and Masrani, they have already decided to green-light the lab creation of genetic hybrids obtained by mixing the DNA of potentially lethal animals.

Enter the hyperreal king of this brave new genetic world: the chameleon-like Indominus rex, the result of the genetic manipulation of the genomes of Tyrannosaurs rex, Velociraptor, Carnotaurus (more on this dinosaur in a moment), various abelisaurs, a cuttlefish, a tree frog, and who knows what else. Thanks to this weird genetic soup, the Indominus is able to camouflage himself with Predator-like finesse. The idea for his ability comes directly from the second novel written by Crichton, The Lost World (1995), which Spielberg transferred to the silver screen in 1997. In the novel, the South American abelisaur Carnotaurus behaved as if it had cuttlefish-like chromatophores and chameleon-like camouflaging abilities, a most bizarre idea probably inspired by artist-turned amateur palaeontologist Stephen Czerkas’ fringe theories (Crichton 1995: 386-387) [5]. In keeping with the usual muted palette sported by the dinosaurs of the franchise, the new Jurassic World hybrid is a ghostlike grey-white which, at the very least, is a departure from “shit-green” hues [6].

“You didn’t ask for reality, you asked for more teeth.” Indominus rex toy. © Hasbro. Source: ScreenRant.

Now, let’s try and put this hyperreality in perspective: in our capitalistic society, the hyperreal can be understood as a sort of corporate response to the socio-cognitive arms race between habituation and the subversion of expectations, as it entails ever bigger, faster, grander spectacles to evade normalisation, boredom, and disinterest. However, since habituation can be only delayed, the resulting hyperreal arms race is very much built like an inescapable loop. Much like Aldous Huxley’s fictitious soma, this loop is reflected in our current consumeristic, corporate-led need for an ever-increasing dopamine fix to keep us satisfied through multimedia content. For all intents and purposes, we are hyperreal junkies (cf. Smail 2014).

Truth be told, all of this makes for quite an interesting and fresh premise for another shot at the Jurassic franchise. Rather disappointingly, there is no space for such reflections in the movie. Instead, what follows is the usual, by-the-book monster movie script, with the escape of the devilish Indominus from its enclosure, keen on wreaking havoc on the park, and the ensuing clash between hubristic entrepreneurs and their minions, who want to capture their multimillion-dollar investment alive, versus the heroes who ultimately save the day. Despite the latter’s efforts, the end result is another avoidable carnage. It does not matter that, in real life, the 1975 Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA established solidly moral and precautionary guidelines on biotechnological research. The investors of Masrani Global Corporation (the fictional company that bought InGen, the original start-up that brought the dinosaurs back to life in Jurassic Park) couldn’t care less about the Isla Nublar incident depicted in the first movie and the San Diego massacre shown in the Lost World sequel. The only loop we see fully at work in Jurassic World is the ongoing failure of biotechnology startups.

A monster movie that hates dinosaurs?

In order to fully appreciate the in-universe corporate and multifaceted failure behind the umpteenth Jurassic slaughter, I’d like first to turn our attention back to the sorely antiquated body plan and the questionable design of the dinosaurs depicted in Jurassic World. When it is not slavishly traced over the already outdated baupläne of the first movie, the animal body structure is completely imaginary, as in the case of the demonic restyling of the pterosaur Dimorphodon (no, neither Dimorphodon is a dinosaur; Conway 2014; Myers 2015; Holtz 2015; on Dimorphodon see Witton 2015). If we assume that the in-universe palaeontological knowledge has progressed more or less like it did in the real-world, then the fact that Masrani decided to rely on such improbable hyperreal dinosaurs – which I doubt were charismatic enough as the family-friendly face of the Jurassic brand, given the aforementioned disasters – is mind-boggling, especially when we have been discovering astonishing fossils of feathered and non-feathered dinosaurs of all shapes and forms since 1996. Could this hyperreal version of a prehistoric park have any chance of success in our day and age, with its outdated monstrosities’ appearance falsified by the increment in our scientific knowledge and with all the worldwide dinophiles able to list effortlessly their innumerable morphological blunders? Indeed, when the film came out, the reception of its de-extinct beasts was so bad that the hashtag #buildabetterfaketheropod took the social media palaeoart circles by storm with the intention to create a “fictional hybrid dinosaur […] more scientifically accurate and visually appealing than the Indominus Rex” (Know Your Meme 2016).

Interestingly, vertebrate palaeontologist Victoria Arbour suggested that Jurassic World is a monster movie that explicitly hates dinosaurs, both in terms of the in-universe fiction (with the economic exploitation of these animals for the visitors’ entertainment) and as real-world entities (that is, dinosaurs as epistemological entities subjected to constant update and revisions) (Arbour 2015).

However, I think that the real problem underneath it all, the capital sin hidden in the very fabric of the whole Jurassic Park concept and franchise, is Michael Crichton’s own disregard for real science. Crichton had a highly sceptical if not reactionary vision of science which informed many of his novels. As Sandy Becker wrote, “it’s hard for a scientist to feel friendly towards Michael Crichton. [Crichton] seems really hostile to science and to many of the people who practice it” (Becker 2008: 82-83). In Crichton’s world, scientific research, technology, and private tech companies are often barely distinguishable, and scientists are usually portrayed as mere pawns or active con-conspirators in cahoots with naïve tycoons or cut-throat techno-capitalists. Despite his academic background in biological anthropology and medicine, Chrichton’s understanding of the epistemology, history, and philosophy of science was anachronistically stuck in a Romantic vision of unbridled Frankensteins and malfunctioning human-made horrors ready to unleash their fury upon us (what is Jurassic Park if not Westworld with dinosaurs?). It is not Jurassic World that hates dinosaurs; it was Crichton himself who hated scientists and scientific research. And dinosaurs just happened to be on his way.

Scientific nonsense and where to find it

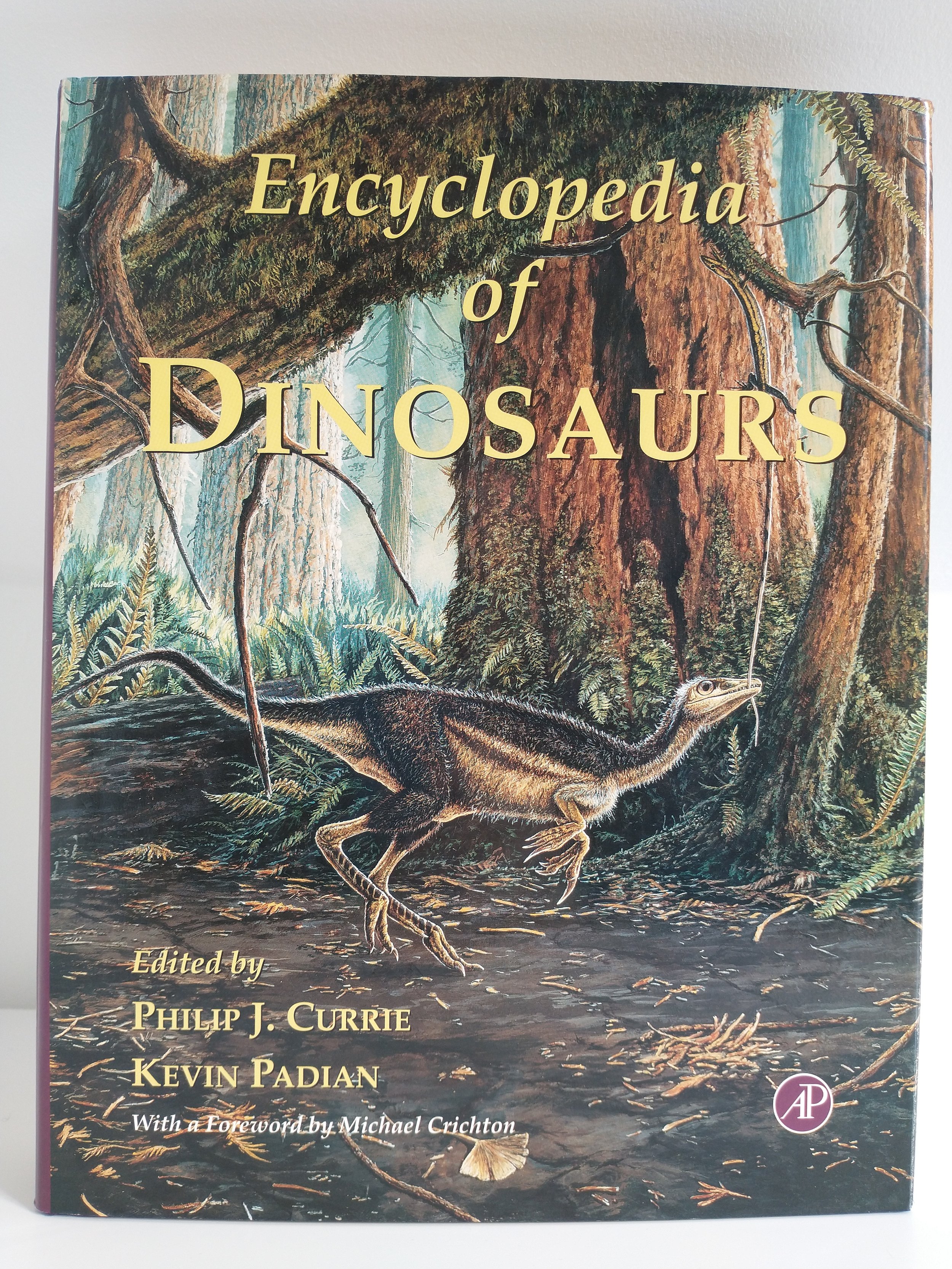

Thanks to the success of the Jurassic Park franchise, Crichton was invited to write a foreword to the authoritative 850+ page-long Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, published in 1997. In it, after a long exposition of various informal theories entertained “over the years” to try and “explain the fact that dinosaurs excite the imagination of adults and children throughout the world”, only to focus exclusively on children (Crichton 1997: xxv), Crichton wrote:

“Although we know far more about dinosaurs than we did a few decades ago, the truth is that we still know very little. We don’t really know what these creatures looked like, or how they behaved. We have some bones, impressions of skin, some trackways, and many fascinating speculations about their biology and social organization. But what hard evidence remains of their long-vanished world is tantalizing and incomplete. And so they still provoke our dreams. And, probably, they always will.” (Crichton 1997: xxvi)

Even if we contextualize the passage in the late Nineties, this was quite a weird statement to make. First, it felt blatantly out of place as a preface to one of the very first academic volumes featuring the revolutionary discovery of feathered dinosaurs, which vindicated the theories of Yale palaeontologist John Ostrom (1928-2005), to whom the volume is indeed dedicated (Currie and Padian 1997: xxix-xxx). Furthermore, a feathered, svelte dinosaur, courtesy of palaeoartist Michael Skrepnick, was featured right on the cover, showing how scientific knowledge progresses steadily and how (palaeo)art and science could work together to enhance each other’s explanatory and emotional power (an idea which Crichton probably disliked, as we will see shortly). Second, it belittled and infantilised palaeontology by associating tout court this scientific discipline with “children”, “speculations”, and “dreams”. Third, it conveniently ignored the cumulative process behind scientific research and re-imagined the future of dinosaur science as its present (as Crichton thought it was), that is, stuck in a perpetual unknowability. Here, Crichton committed the fallacy of presentism, which was pretty disconcerting for a celebrated novelist specialized in techno-scientific futuristic thrillers.

Sinosauropteryx prima, “the feathered dinosaur recently discovered in China, lends additional credence to the hypothesis of a close relationship between dinosaurs and birds. Illustration by Michael Skrepnick.” Text from Currie and Padian (1997): iv. © 1997 Academic Press/Elsevier. For an overview of the current knowledge about this dinosaur (and its astonishing coloured coat) see Benton 2021: 28-41.

Crichton reiterated his beliefs in an address delivered at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) on 25 January 1999. On that occasion, the novelist said clearly that there was no point in doing the necessary homework before writing a sci-fi novel:

“in a story like Jurassic Park, to complaint of inaccuracy is downright weird. Nobody can make a dinosaur. Therefore the story is a fantasy. How can accuracy have any meaning in a fantasy? It’s like the reporters who asked me if I had visited genetic engineering firms while doing my research. Why would I? They don’t know how to make a dinosaur.” (Crichton 1999)

Crichton just wanted to write one of those “corny movies of people and dinosaurs together that I had loved in childhood” like “King Kong, One Million Years BC, all of that”, and that the “natural world is entirely irrelevant” to storytelling. In any case, as he replied to his critics,

“no one knows what dinosaurs looked like or how they behaved. Technical advisors can’t tell you, because no one knows. We have skeletal remains, some trackways, and some impressions of skin texture. But the minute you start adding muscles and skin color and movement and behavior, you’re guessing. Therefore the film portrayal of dinosaurs is fantasy. A novelist imagined their behavior. Artists imagined their appearance. Their actions were honed, and repeatedly revised by artists at Industrial Light and Magic until they looked right to Steven Spielberg. There is nothing remotely real about them.” (Crichton 1999)

In the 1990s there was a lot that scholars didn’t know, but they knew a lot more than their predecessors in terms of palaeobiology, taphonomy, and biomechanics – and I want to stress A LOT MORE (especially at the turn of the century; e.g., Alexander 2006). Also, there is a radical difference between unchecked wild speculations to bolster a “corny movie” and scientifically informed, or epistemically warranted, hypotheses.

Paradoxically, at the end of his first dinosaur novel, Crichton listed all the palaeontologists and palaeoartists whose works inspired him and “whose reconstructions incorporate the new perception of how dinosaurs behaved”. The names included some among the most prominent figures in the field: “Robert Bakker, John Horner, John Ostrom, […] Gregory Paul […] Kenneth Carpenter, Margaret Colbert, Stephen and Sylvia Czerkas, John Gurche, Mark Hallett, Douglas Henderson and William Stout” (Crichton 1991: 401). Even the very idea at the narrative core of Jurassic Park itself – resurrecting dinosaurs thanks to the DNA extracted from blood preserved as stomach contents in the mosquitoes encased in prehistoric amber – was already presented in a piece published in 1985 by Charles Pellegrino and called “Dinosaur Capsule.” Crichton might not have been aware of this article (because he only acknowledged Pellegrino in a subsequent edition of his novel), but in the very first edition he conceded that his ideas about paleo-DNA were drawn from “the research of George Poinar, Jr. and Roberta Hess, who formed the Extinct DNA Study Group at Berkeley” (Crichton 1991: 401; see Jones 2018). Crichton even consulted with Poinar while working on the script of the first movie (Boissoneault 2018). And yet, in 1999, every source of inspiration was magically swept under the rug. It’s just fantasy, so no one knows anything, everything is invented, and thus anything goes. In doing this, Crichton – a multimillionnaire novelist whose stories adapted for the silver screen raked in a grand total of $3,336,847,957, making him the 15th “Top Grossing Story Creator at the Worldwide Box Office” (The Numbers 2023) – at once disavowed the priority rule in science, showed a cavalier lack of good manners (you always acknowledge your predecessors and give credit were credit is due), and aligned himself with the despicable corporate trend that robs intellectual property creators of their rights, from Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster to Jack Kirby.

It wasn’t just dinosaur science or paleo-DNA the topics in which Crichton wasn’t very much interested. Evolutionary biology clearly wasn’t his forte either. For instance, in the script of the first movie, he put the following words in the mouth of his alter ego, mathematician Ian Malcolm, as the character is having a discussion with de-extinction visionary entrepreneur John Hammond: “this is no species that was obliterated by deforestation or the building of a dam. Dinosaurs had their shot. Nature selected them for extinction”. As James H. Spence recaps, according to Malcolm “nature is to be respected, and if nature selects dinosaurs for extinction, then dinosaurs should remain extinct” (Spence 2008: 100). Of course, the idea that environmental constraints might actually select a taxon for extinction is utter nonsense. At best, it is a falsified, pre-Dinosaur Renaissance legacy from a time when orthogenetic dogmas held that the evolution of species was organized much like the life history of a single organism, with species destined either to progress along a predetermined evolutionary route, regress to primitive or degenerating forms until senescence and extinction, or stay put across millions of years as living fossils stuck forever in time (for the preconceived notions behind this point of view and its moral consequences, see Ambasciano 2019: 49 ff.; for dinosaur science and evolutionary biology cf. Padian and Burton 2012). No species is “selected for extinction”, nature is not a teleological agent with a selective and teleological agenda, and dinosaurs, by the way, rank among the most successful groups of vertebrates in the history of the planet – so successful that one group of dinosaurs survived the mass extinction of the late Cretaceous and gave rise to the wonderful diversity of birds we have today. A case could be made for us to be still living in the era of dinosaurs, for there are approximately over 11,000 species of birds against just 6,000 species of mammals. Which, ironically, is suggested in the final shot of Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, when palaeontologist Alan Grant watches with relief a flock of pelicans flying over the sea. If Crichton really bothered to read the works of those pioneering Dinosaur Renaissance palaeontologists he acknowledged in his novel, it would have been nice to hear Grant’s objections to Malcolm’s outdated and apodictic statements [7].

Honouring Crichton’s work?

Movies are not just simple pastimes or fun time-killers. Movies can have real-life consequences. Just like the best novels, poetry, theatre performances, mythological and religious stories, graphic novels, or comic books, they are transformative experiences. They inspire us. They serve as cautionary tales. They provide us with negative or positive role models. They explore fascinating virtual realities. They teach us lessons or suggest what to do, what not to do, what should be best avoided and what could work in the fictitious and safe virtual setting of our minds. A movie is not reality itself, for sure, but when all the cinematic components work in perfect unison, a movie becomes a representation of reality so believable that its rational and emotional disassembling as a fiction can be a significant meta-cognitive effort even for the most adept cinemagoing aficionados: to mentally represent the cinematic representation as a cultural artifact is hard and unnatural (cf. Gallese and Guerra 2015).

My copies of Crichton’s dinosaur novel: the English one (right; London: Arrow, 1991), and the third italian reprint (left; Milan: Garzanti, June 1993). If I recall correctly, I might have read the Italian edition in the summer of ’93, well before the movie came out on 12 September. I was 9 years old and already a longtime dinophile. Private collection.

Sometimes, the consequences of cinemagoing are positive and even life-changing. Other times, the repercussions are less benign. Just a couple of examples might suffice here: the spike in dalmatians pups bought and soon abandoned after the live action rendition of Disney’s 101 Dalmatians (1996) and the drastic decrease of the clownfish population in the aftermath of Pixar’s Finding Nemo (2003; see Zarrella 1997 and Alleyne 2008). Surprisingly, insofar as Jurassic Park’s impact on society was concerned, Crichton leaned towards the latter outcome, not because Jurassic Park wasn’t good, mind you, but because science wasn’t up to its task.

In his 1999 AAAS address, Crichton stated that:

“a lot of young people are going to be excited enough by a movie or a novel, to give science a try; to sign up for a course. And my fear is that these kids will conclude that even though Jurassic Park made science seem interesting and exciting, the introductory course proves conclusively that it isn’t.” (Crichton 1999)

The fact that we have been living for years now in the Golden Age of dinosaur palaeontology, with a new generation of students enrolling in natural science faculties in droves thanks to the impact the first Jurassic Park movie had on their lives, falsifies Crichton’s thesis: far from being let down by the supposedly stale methods they encountered at the university, students enthusiastically embraced science and were eager to do their part to improve scientific knowledge (McKie 2018; Naish 2021: 84). The reality of palaeontology is far more intriguing and interesting than any work of fiction but, of course, Crichton, ever so dismissive of scientists and their work and eager to see top scientific research transmogrified into prosumeristic edutainment with media-savvy press tours (as he declared in his 1999 address), couldn’t really see the science beyond the fiction, nor the joy and the passion behind scientific research (some years ago, I dedicated a critical post on such topics for my former Italian blog, to which I refer the interested reader; Ambasciano 2018).

Despite Crichton’s fears, dinosaurs have in fact an untapped potential to be used as representative for scientific literacy, as well as to teach the basics of evolutionary thought, because of their unmatched charismatic aura. As palaeontologist Scott Sampson noted,

“first, unlike many topics in science, dinosaurs inspire rather than intimidate our imaginations. Second, as the primary exemplars of prehistoric Earth, dinosaurs serve as able, even ideal, guides to an exploration of the deep past. Third, the living descendants of dinosaurs, birds, are much beloveds and keenly observed, forging a robust link between past and present […]. Fourth […] the interdisciplinary nature of paleontology means that dinosaurs provide excellent access points to topics as diverse as genetic cloning and plate tectonics [My note: Sampson also lists palaeoclimatology as a proxy to discuss current climate change and the relevance of the K/Pg extinction of non-avian dinosaurs to ongoing anthropogenic extinction of contemporary fauna]. Finally, dinosaurs possess tremendous potential to help convey the transformational Great Story [My note: that is, the “Universe Story” or the “epic of evolution”, as Sampson also calls it] and, in so doing, foster evoliteracy.” (Sampson 2009: 277)

I am afraid that Chrichton’s gloomy prediction from 1999, informed by his evoilliteracy, might become a self-fulfilling prophecy. What can dragon-like monsters like the Indominus rex or the Stegoceratops possibly contribute to evoliteracy? Apart from a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo as a screesaver silhouette in Jurassic World, the latter was to be featured in all its abominable glory in a dedicated scene before Trevorrow’s son, of all people, suggested to his dad to eliminate it in order to focus on the uniqueness of the Indominus (De Semlyen 2015). Apparently, the suggestion came in a bit late into production, because the design of the beast had already reached the developers’ desks at Hasbro headquarters, and so they produced a Stegoceratops action figure with a special “bashing attack!” feature. How many, once acquainted with the fictitious nature of that critter and its apparently scientifically legitimate name, would end up bashing or infantilising palaeontology instead, thinking something to the tune of “they’re all alike anyway, you know? Dinosaurs and dragons. It’s all bones, who really cares?”. Crichton, for one, didn’t seem to care, so, in this sense, Trevorrow’s mission to “honor Michael Crichton’s work” is accomplished: Jurassic Park has finally and unashamedly embraced its original and corny monster-movie roots (cf. Erbland 2022).

Ceci n’est pas un dinosaure. Stegoceratops. © Hasbro. Source: Empire.

The best comment I found about this sorry situation comes from Donald Prothero, a palaeontologist with a forty-year experience in teaching college geology and palaeontology:

“every lecture I give about earthquakes or volcanoes or tsunamis and waves must waste a lot of time debunking Hollywood myths. Every time I teach about dinosaurs, I spend a lot of time undoing the damage of previous Hollywood movies—and now the lazy bad science of Jurassic World means I’ll have a lot of new myths to debunk. Even though most movies are fictional, most people do get their perceptions about science and nature from movies, because they sure don’t get much in school and most don’t watch documentaries, either.” (Prothero 2015)

Conclusion: Do we really need these hyperreal monstrosities?

When I wrote the first version of this post way back in 2015, I concluded with some reflections on the blatant disregard for dinosaur anatomy and the plagiarised illustrations and silhouettes used on the Jurassic World website (Martyniuk 2014; Mellow 2014), the sexist tropes showcased by the movie itself (Abad-Santos 2015), and the generational and nostalgic bait which elevated to blockbuster stardom ultra-derivative plots (Lang 2015; Hoad 2015). And yet, none of these issues could prevent people who longed to live again the cinematic experience of their youth to come in droves and revisit the park… and I, for one, was there too (that is, in the cinema, not at the park – lucky me). Trevorrow’s nostalgic revival was enormously successful. When it debuted, Jurassic World became “the first film to take more than $500m (£322m) at the global box office on its opening weekend” (Hassan 2015). Today, in early 2023, it still features as #8 in the Top Lifetime Grosses at the box office, with a whopping worldwide gross of $1,671,537,444 (Box Office Mojo 2023).

In the wake of two lacklustre sequels, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018) and Jurassic World Dominion (2022), which boast respectively 47% and an abysmal 22% critics score on Rotten Tomatoes (Rotten Tomatoes 2023), I admit that I was quite surprised by the ability of the franchise to be still profitable: even though fatally affected by the law of diminishing returns, the two sequels managed to rake in a Worldwide Lifetime Gross of, respectively, $1,310,466,296 and $1,001,978,080 (as per the data reported in Box Office Mojo as of mid-February 2023). Yet, their plots became more bonkers as time went by. Yes, we finally had some fully feathered dinosaurs as a consolation prize for enduring the franchise (still, the results were anatomically grotesque) [8], but in exchange we’ve got another over-the-top diabolical, hybrid monster (the Indoraptor), a questionable retcon involving human cloning, a character (a scientist, obviously) impregnating herself with her own clone which is basically herself but rid of a heritable genetic disease (the less is said about this convoluted plot point, the better), and, in a twist worthy of a Christopher Nolan’s plot, genetically modified prehistoric mega-locusts from hell threatening to devour all the world’s harvests. What the heck happened to the franchise? Seriously, the dinosaurs of what is arguably the most famous theme park in the world have become an afterthought, if not a nuisance in the way of the plot. Alas, there is only so much you can do with monsters and, at long last, the hyperreal images managed to exhaust all their possibilities. There is no more “WOW!” factor left for them.

It is time to let the genetic hybrids and the contrived plots they are a part of rest in peace. We don’t need this malfunctioning park anymore. We’ve endured the hostage crisis caused by the false dichotomy according to which Hollywood has to choose between science and art, between boredom and fun, between scientifically-informed verisimilitude and monsters, for far too long. Crichton and Trevorrow chose the latter options, and the rest is history. However, the success of products able to combine the best scientific knowledge at disposal at the time with documentary storytelling, from bold, pioneering shows like Il pianeta dei dinosauri (RAI, Italy 1993) and Walking with Dinosaurs (BBC, UK 1999) to the stellar Prehistoric Planet (executively produced by Jon Favreau in collaboration with the BBC Studios Natural History Unit, narrated by David Attenborough with a cinematic soundtrack composed by Hans Zimmer, supervised by a host of scientific consultants including palaeontologist extraordinaire Darren Naish, and released on Apple TV+ in 2022) shows that another kind of scientifically informed entertainment is possible.

Goodbye, Jurassic franchise, and thanks for all the mosasaurs.

Notes

Post updated on 20 February 2023.

This post presents an updated, revised, and expanded version of a brief essay originally written in Italian and published as “Jurassic World: il monster movie che ci meritiamo, tra iperrealtà postmoderna e nostalgia riciclata” on 24 June 2015 on my former personal blog Tempi Profondi. A postscript focused on Crichton’s ideas about science and climate change in particular is available here: The Toxic Legacy of Michael Crichton, 15 February 2023.

[1] The Making of Jurassic Park. DVD documentary.

[2] To be fair, the raptors were supposed to sport a striped tiger-like coat before the release of the film, survived in Kenner’s Jurassic Park toy line.

[3] Today we are even able to reconstruct the coat colours sported by feathered dinosaurs – revealed to be far from “shit-green” – thanks to the traces left by melanosomes. Some new feathered dinosaurs are so phylogenetically distant from their extant relatives, the birds, that some scholars speculate that protofeathered integument might have been the ancestral condition of all dinosaurs (cf. Chang et al. 2003 for an overview of the first discoveries; on melanosomes see Switek 2013: 155-160; on protofeathered integument cf. Godefroit et al. 2014; for the impact of new technologies on dinosaur science, see Benton 2019 and Benton 2021).

[4] Some scholars have noted how Baudrillard’s works contain “a profusion of scientific terms, used with total disregard for their meaning and, above all, in a context where they are manifestly irrelevant” (Sokal and Bricmont 1997: 143). One could cynically make the case that, as the contemporary hyperreal loss of reality caused by the interaction between social media, technology, and politics shows, science literacy does not matter anyway. Others might be justified in thinking that contemporary post-truth, truthiness, and the penchant for “alternative facts” are but the poisoned apple of an antireal, antiscience, and postmodern turn that has led to catastrophic societal outcomes (Kempner 2014: 117; cf. Kakutani 2018 and Ambasciano 2021). While this is not the place to discuss such topics, we’ll explore some of these themes in relation to Michael Crichton’s own ideas in the following paragraphs and in the next post in the series.

[5] Cf. John N. Wilford’s interview with Czerkas published in Discover (Jan.-June 1989, p. 4) where the latter, after having talked about the discovery of fossilised dermal tubercles on the skin of Carnotaurus by Argentinian palaeontologist José Bonaparte, states that dinosaurs might have been colourful before speculating, without providing any proof, that they might have been even capable of changing colours like chameleons. In an encyclopaedic academic volume prefaced by none other than Michael Crichton, Czerkas stated that the “tuberculate squamation” analogous to that found in some dinosaurs (which go unnamed) is unlike that typical of lizards and snakes and is instead found today “on extant chameleons” (Czerkas 1997: 669). Curiously, while Jurassic Park includes Czerkas’ name in the Acknowledgments (Crichton 1991: 401), Crichton’s 1995 sequel The Lost World, which featured the chameleon-like Carnotaurus, did not (as far as I can remember, Carnotaurus is never explicitly mentioned but just described in the novel; however, it is featured and named in the opening spread featuring a map of the island were the action takes place and a panoply of dinosaurs by Gregory Wenzel). Czerkas, who was a palaeoartist with a background as a special effect artist, lent his talents to the idea that birds were not the evolutionary descendants of theropod dinosaurs even when such thesis was disproved (Czerkas and Czerkas 1990; Czerkas and Feduccia 2014). Insofar as the scaly skin of the Jurassic Park dinosaurs is concerned, Czerkas also supported, with various degrees of epistemic warranty, the idea that iguanas provided a good dermatological proxy to reconstruct the skin of both sauropods and stegosaurs (cf. Czerkas 1987; Czerkas and Czerkas 1990; Czerkas 1997; for Czerkas’ field involvement with the discovery of additional Carnotaurus’ fossilised skin in Argentina see Czerkas and Czerkas 1989: 2-6).

[6] As Robert DeSalle and David Lindley remarked way back in 1997, “traditionally, dinosaurs have been portrayed in browns and greens, because (traditionally) they were thought of as large reptiles. But if you think of them as precursors to birds, a whole new range of colors comes to mind. The chameleonlike carnosaur [sic; i.e., Carnotaurus] of Site B, able to change the color of its skin at will and disguise itself as a chain-link fence, may be the product of a heightened imagination, but apart from that, why not give your fictional and cinematic dinosaurs bright colors and flabbergasting noises?” (DeSalle and Lindley 1997: 164).

[7] That Crichton didn’t care about his evoliteracy became painfully clear in his 1995 sequel to Jurassic Park, The Lost World. In the Acknowledgements, after a significant list of people and scientists whose “work, and […] speculations” he was “indebted to” (including Stephen Jay Gould, Niles Eldredge, John Horner, and John Ostrom), Crichton felt pre-emptively compelled to “remind the reader that a century and a half after Darwin, nearly all positions on evolution remain strongly contented, and fiercely debated” (Crichton 1995: 431).

[8] Jurassic World Dominion also treated its viewers to a lengthy prologue shot documentary-style and set 65 million years ago which (A) sported all sorts of inaccuracies and anachronistic animals (the more CGI progresses to astounding results, the more Hollywood palaeoartistic reconstructions seem to regress to a pre-1993 state), and (B) featured a nonsensical kaiju-like feud between a Tyrannosaurus and a Giganotosaurus – who did not live at the same time and neither were they from the same hemisphere – which continued in the present (the third act of the movie), after they were cloned and brought back to life (by virtue of Lamarckian genetic memeories?).

Refs.

Abad-Santos, Alex. 1025. “A Guide to Jurassic World’s Sexism Controversy.” Vox, 16 June. https://www.vox.com/2015/6/16/8788641/jurassic-world-sexism [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Alexander, R. McNeill. 2006. “Dinosaur Biomechanics.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Biological Sciences 273(1596): 1849-1855. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3532

Alleyne, Richard. 2008. “Demand for Real Finding Nemo Clownfish Putting Stocks at Risk.” The Telegraph, 26 June, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/earthnews/3345594/Demand-for-real-Finding-Nemo-clownfish-putting-stocks-at-risk.html [Last Access 12 February 2023].

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2018. “La divulgazione scientifica al tempo del prosumatore.” Tempi Profondi, 26 October. https://tempiprofondi.blogspot.com/2018/10/la-divulgazione-scientifica-al-tempo.html

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2019. An Unnatural History of Religions: Academia, Post-truth and the Quest for Scientific Knowledge. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2021. “An Evolutionary Cognitive Approach to Comparative Fascist Studies: Hypermasculinization, Supernormal Stimuli, and Conspirational Beliefs.” Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture 5(1): 23-39. https://doi.org/10.26613/esic.5.1.208

Arbour, Victoria. 2015. “Why Does Jurassic World Hate Dinosaurs?” Pseudoplocephalus, 16 June. http://pseudoplocephalus.blogspot.co.uk/2015/06/why-does-jurassic-world-hate-dinosaurs.html [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Baird, Robert. 1998. “Animalizing Jurassic Park’s Dinosaurs: Blockbuster Schemata and Cross-Cultural Cognition in the Threat Scene.” Cinema Journal 37(4): 82-103. https://doi.org/10.2307/1225728

Bakker, Robert. 2004. “Dinosaurs Acting Like Birds, and Vice Versa – An Homage to the Reverend Edward Hitchcock, First Director of the Massachusetts Geological Survey.” In Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds, edited by Philip J. Currie, Eva B. Koppelhus, Martin A. Shugar and Joanna L. Wright, 1-11. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1995 [1981]. Simulation and Simulacra. Translated by Sheila Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Originally published as Simulacres et Simulation. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

Becker, Sandy. 2008. “We Still Can’t Clone Dinosaurs.” In The Science of Michael Crichton: An Unauthorized Exploration Into the Real Science Behind the Fictional Worlds of Michael Crichton, edited by Kevin R. Grazier, 69-84. Dallas: Benbella Books.

Benton, Michael J. 2019. The Dinosaurs Rediscovered. London: Thames & Hudson.

Benton, Michael J. 2021. Dinosaurs: New Vision of a Lost World. London: Thames & Hudson.

Boissoneault, Lorraine. 2018. “Jurassic Park’s Unlikely Symbiosis with Real-World Science.” Smithsonian, 15 June. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/jurassic-park-reveals-delicate-interplay-between-science-and-science-fiction-180969331/ [Last Accessed 12 February 2023].

Box Office Mojo. 2023. “Top Lifetime Grosses”. Data as of Feb 7, 1:38 PST. https://www.boxofficemojo.com/chart/ww_top_lifetime_gross/?area=XWW

Cau, Andrea. 2015. “Cosa sono Tyrannosaurus, i raptor e Indominus?” Theropoda, 23 June. http://theropoda.blogspot.be/2015/06/cosa-sono-tyrannosaurus-i-raptor-e.html [Last accessed 20 June 2022].

Chang, Mee-Mann, Pei-ji Chen, Yuan-qing Wang and Yuan Wang (eds). 2008 [2003]. The Jehol Biota: The Emergence of Feathered Dinosaurs, Beaked Birds and Flowering Plants. English Edition Edited by De-sui Miao. London and Burlington: Academic Press.

Conway, John. 2014. “Scientists disappointed Jurassic World dinosaurs don’t look like dinosaurs.” The Guardian, 4 December. https://www.theguardian.com/science/lost-worlds/2014/dec/04/scientists-disappointed-jurassic-world-dinosaurs-movie-film [Last accessed 12 February 2012]

Crichton, Michael. 1991. Jurassic Park. London: Arrow.

Crichton, Michael. 1995. The Lost World. London: Arrow

Crichton, Michael. 1997. “Foreword.” In Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, edited by Philip J. Currie and Kevin Padian, xxv-xxvi. San Diego and London: Academic Press.

Crichton, Michael. 1999. “Why Science is Media Dumb: The Story. Address was recorded at the American Association for the Advancement of Science on January 25 1999, and broadcast on the Science Show on April 3, 1999.” ABC, http://www.abc.net.au/science/slab/crichton/story.htm [Last Accessed 13 January 2023].

Currie, Philip J. and Kevin Padian. 1997. “Dedication.” In Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, edited by P. J. Currie and K. Padian, xxix-xxx. San Diego and London: Academic Press.

Czerkas, Stephen A. 1987. “A Reevaluation of the Plate Arrangement on Stegosaurus stenops.” In Dinosaurs Past and Present. Vol. 2, edited by Sylvia J. Czerkas and Everett C. Olson, 82-99Seattle and London: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in association with University of Washington Press.

Czerkas, Stephen A. 1997. “Skin”. In Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, edited by Philip J. Currie and Kevin Padian, 69-675. San Diego and London: Academic Press.

Czerkas, Stephen A. and Sylvia Czerkas. 1989. My Life with the Dinosaurs. New York: Byron Preiss.

Czerkas, Stephen A. and Sylvia Czerkas. 1990. Dinosaurs: A Global View. Limpsfield, UK: Dragon’s World.

Czerkas, Stephen A. and Alan Feduccia. 2014. “Jurassic Archosaur is a Non-dinosaurian Bird.” Journal of Ornithology 155: 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-014-1098-9

Daly, E. 2014. “Jurassic World: What We Know So Far...” Radio Times, 15 October. http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2014-10-15/jurassic-world-what-we-know-so-far [Last Accessed 24 June 2015]

De Semlyen, Phil. 2015. “Empire Spoiler Podcast: Ten Secrets of Jurassic World.” Empire, 21 October. https://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/empire-spoiler-podcast-ten-secrets-jurassic-world/ [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

DeSalle, Robert and David Lindley. 1997. The Science of Jurassic Park and the Lost World, or, How to Build a Dinosaur. London: HarperCollins.

Erbland, Kate. 2022. “Why Colin Trevorrow Didn’t End ‘Jurassic World’ Trilogy with ‘Fantasy Movie’ About ‘Chomping’ Dinosaurs”. IndieWire, 11 June. https://www.indiewire.com/2022/06/jurassic-world-dominion-ending-1234730334/ [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Gallese, Vittorio and Michele Guerra. 2015. Lo schermo empatico: cinema e neuroscienze. Milan: Cortina.

Godefroit, Pascal, Sofia M. Sinitsa, Danielle Dhouailly, Yuri L. Bolotsky, Alexander V. Sizov, Maria E. McNamara, Michael J. Benton and Paul Spagna. 2014. “A Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaur from Siberia with Both Feathers and Scales.” Science (345)6195: 451-455. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1253351

Gould, Stephen J. 1996. “Dinomania.” In Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History. London: Jonathan Cape, pp. 221-237. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674063426.c26. Originally published in 1993 as “Dinomania. Jurassic Park, directed by Steven Spielberg, screenplay by Michael Crichton, by David Koepp. Universal city studios; The Making of Jurassic Park by Don Shay, by Jody Duncan, Ballantine, 195 pp., $18.00 (paper); Jurassic Park, by Michael Crichton, Ballantine, 399 pp., $6.99 (paper).” New York Review of Books, 12 August. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1993/aug/12/dinomania/?pagination=false [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Hassan, Genevieve. 2015. “Jurassic World: The Secret to its Success.” BBC, 15 June. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-33078934 [Last Accessed 10 July 2022].

Havstad, Joyce C. and N Adam Smith. 2019. “Fossils with Feathers and Philosophy of Science.” Systematic Biology 68(5): 840-851. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syz010

Hoad, Phil. 2015. “Nostalgia, 3D – and June – Helped Jurassic World Beast All Before It.” The Guardian, 17 June, http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jun/17/global-box-office-jurassic-world-spy [Last Accessed 12 February 2023].

Holtz, Thomas Jr. 2015. “Review: So What About Jurassic World?” Los Alamos Daily Post, 17 June. https://ladailypost.com/review-so-what-about-jurassic-world/ [Last Accessed 22 February 2023]

Isbell, Lynne A. 2006. “Snakes as Agents of Evolutionary Change in Primate Brains.” Journal of Human Evolution 51(1): 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.12.012

Isbell, Lynne A. 2009. The Fruit, the Tree and the Serpent: Why We See So Well. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jones, Elizabeth D. 2018. “Ancient DNA: A History of the Science Before Jurassic Park.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 68–69: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2018.02.001

Kakutani, Michiko. 2018. The Death of Truth. London: William Collins.

Kempner, Brandon. 2013. “Feathering the Truth.” In Jurassic Park and Philosophy: The Truth Is Terrifying, edited by Nicolas Michaud and Jessica Watkins, 111-120. Chicago: Open Court.

Know Your Meme. 2016. “#BuildABetterFakeTheropod.” https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/buildabetterfaketheropod [Last Accessed 7 February 2023].

Lang, Brent. 2015. “Box Office: ‘Jurassic World’ Sets Global Record With $511.8 Million Debut.” Variety, 14 June, https://variety.com/2015/film/news/jurassic-world-global-box-office-record-1201519430/ [Las Accessed 12 February 2023]

Martyniuk, Matt. 2014. “Is Jurassic World Stealing from Independent Illustrators?” Dinogoss, 30 November. http://dinogoss.blogspot.co.uk/2014/11/is-jurassic-world-stealing-from.html [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

McKie, Robin. 2018. “How Jurassic Park Ushered in a Golden Age of Dinosaurs.” The Guardian, 23 December. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/dec/23/jurassic-park-film-inspires-new-era-of-dinosaur-discoveries [Last Accessed 12 February 2023].

Mellow, Glendon. 2014. “Jurassic World Butting Heads with Paleoillustrators.” Symbiartic (Scientific American), 20 November. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/symbiartic/jurassic-world-butting-heads-with-paleoillustrators/ [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Myers, P. Z. 2015. “Jurassic World, David Peters, and How to Rile Up Paleontologists.” Pharyngula, 12 June. http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2015/06/12/jurassic-world-david-peters-and-how-to-rile-up-paleontologists/ [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Naish, Darren. 2021. Dinopedia. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Padian, Kevin and Elisabeth K. Burton. 2012. “Dinosaurs and Evolutionary Theory.” In The Complete Dinosaur. Second Edition, edited by M. K. Brett-Surman, Thomas R. Holtz Jr. and James O. Farlow, 1057-1072. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Prothero, Donald. 2015. “It Coulda Been a Contender: A Paleontologist Reviews Jurassic World.” Skeptic, 23 June. https://www.skeptic.com/insight/it-coulda-been-a-contender-a-paleontologist-reviews-jurassic-world/ [Last Accessed 7 February 2023].

Rotten Tomatoes. 2023. “Jurassic World Dominion.” https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/jurassic_world_dominion [Last Accessed 8 February 2023].

Sampson, Scott D. 2009. Dinosaur Odyssey: Fossil Threads in the Web of Life. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Smail, Daniel L. 2014. ““An Essay on Neurohistory.” In Emerging Disciplines: Shaping New Fields of Scholarly Inquiry in and beyond the Humanities, edited by Melissa Bailar, 201-28. Houston: Rice University Press. http://cnx.org/contents/8aa30a5e-9484-4d55-87e3-d53c1cbfb8b2@1.4

Sokal, Alan and Jean Bricmont. 1998. Intellectual Impostures: Postmodern Philosophers’ Abuse of Science. London: Profile Books. Originally published as Impostures intellectuelles. Paris: Odile Jacob.

Spence, James H. 2008. “What Is Wrong with Cloning a Dinosaur? Jurassic Park and Nature as a Source of Moral Authority.” In Steven Spielberg and Philosophy: We're Gonna Need a Bigger Book, edited by Dean A. Kowalski. 97-111. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

St. Fleur, Nicholas. 2015. “A Paleontologist Deconstructs ‘Jurassic World’.” The New York Times, 12 June. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/06/12/science/jurassic-world-deconstructed-by-paleontologist.html [Last accessed 2 July 2022].

Switek, Brian. 2013. My Beloved brontosaurus: On the Road with Old Bones, New Science, And Our Favorite Dinosaurs. New York: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Switek, Brian. 2014. “A Velociraptor Without Feathers Isn’t a Velociraptor.” Laelaps. National Geographic, 20 March. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/a-velociraptor-without-feathers-isnt-a-velociraptor [Last accessed 2 July 2022]

The Numbers. 2023. “Michael Crichton.” 14 February. https://www.the-numbers.com/person/33350401-Michael-Crichton#tab=technical [Last Accessed 14 February 2023]

Witton, Mark. 2015. “Why Dimorphodon macronyx is One of the Coolest Pterosaurs.” Mark Witton’s Blog, 8 June 8. https://markwitton-com.blogspot.com/2015/06/why-dimorphodon-macronyx-is-one-of.html [Last Accessed 12 February 2023]

Zarrella, John. 1997. “With Movie Craze Over, Woman Helps Dalmatians Find Homes.” CNN Interactive, 6 May 6. http://edition.cnn.com/US/9705/06/dal/index.html [Last Accessed 12 February 2023].