James Ungureanu has recently published a peculiar review of my book An Unnatural History of Religions in the March 2022 issue of Isis: A Journal of the History of Science Society (Ungureanu 2022). At the very beginning of his contribution, Ungureanu claims that I was “upset” when I “bemoan[ed] rather petulantly” (sic), “lamented”, and “artlessly proclaim[ed in my book my] deepest convictions”, that is, some Lapalissian statements that are part of the current scientific consensus and are directed against pseudohistorical assertions and neocreationist, esotericist, and spiritualist dogmas that characterise the past, and to some extent the present, of the academic field known as History of Religions (Ungureanu 2022: 219; see Ambasciano 2019). I was certainly not “upset” when I wrote the uncontroversial lines that managed to provoke such a defensive reaction in the reviewer. However, being “upset” is exactly the emotional state I was in after reading Ungureanu’s review. No scholar should get away with such baseless and fanciful descriptions designed to accompany what is a crass misrepresentation of an academic work. In this riposte I will briefly single out Ungureanu’s blatant mistakes, biases, and misattributions.

Hail Sagan

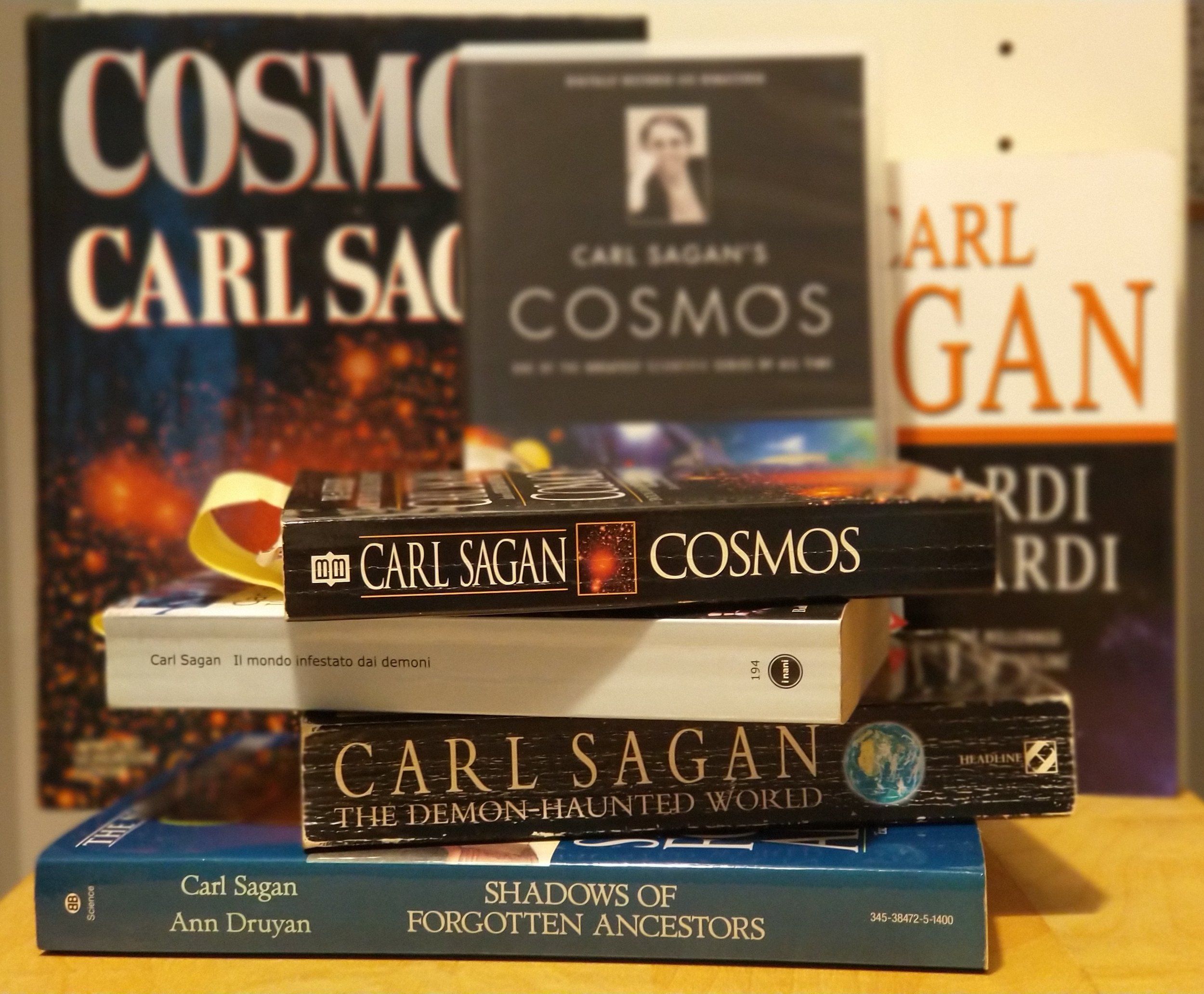

First of all, Ungureanu seems rather annoyed by certain scholars, intellectuals, and scientists cited and recalled in my book. The presence of Cornell University astronomer, NASA astrophysicist, cosmologist, and science populariser extraordinaire Carl Sagan (1934-1996) seems to particularly raffle his feathers. Right at the outset, Ungureanu feels it necessary to alert the serious reader “to what kind of study” my book is based on a “tongue-in-cheek mention of Sagan” inspired by an episode of the animated sitcom Family Guy, which I included in the very first page of my Preface (Ungureanu 2022: 219; my emphasis). I guess irony is not Ungureanu’s forte. However, there seems to be something else beyond a humourless attitude. Ungureanu finds that “the fact that Ambasciano begins and ends his study with musings from Carl Sagan is telling indeed” (Ungureanu 2022: 220; my emphasis). “Telling” of what, exactly? What does Ungureanu find in Sagan’s professional work or heritage so irritating? Has Ungureanu fallen for the debunked idea that Sagan opportunistically exploited his media-savvy presence to propel an allegedly poor scientific career (see Shermer 2002: 493)? Is it perhaps Sagan’s undeniable and stunning success as a science populariser that disturbs Ungureanu? Or is it rather the fact that Sagan was an ardent critic of pseudoscience and Creationism and a supporter of “science and democracy” as a twofold “bulwark against mysticism, against superstition, against religion misapplied to where it has no business being”? (Sagan 1997: 41-42; cf. also p. 19). Ungureanu never says, but the answer comes obliquely from the reviewer’s manifest dislike of what he thinks is the aim of the volume, that is, the imposition of a “reductionistic approach” through a “positivist-materialistic polemic” (Ungureanu 2022: 219). The shocking fact is that, while these methodologies were still rather contentious some fifty years ago in the History of Religions, neither is a particularly controversial or “polemical” topic today in the academic fields of Religious Studies and the Cognitive Science of Religion which form the bulk of the book’s background. However, Ungureanu is not a qualified academic expert in neither the History of Religions nor Religious Studies, much less in the Cognitive Science of Religion. The fact that Ungureanu singles out Sagan as a sort of accomplice to this outdated “positivist-materialistic” conspiracy en plein air is enough to make the learned reader wonder whether Ungureanu is an expert in other fields at all.

Darwin, the bête noire

Sagan is not alone either. The list of henchmen is long. “Tellingly”, Ungureanu insists, “Ambasciano cites Charles Darwin, David Hume, and Xenophanes as ‘notable examples’ of those who have ‘wrestled with religious institutions and dogmas’” and, quite “unsurprisingly”, “the work of Feuerbach, Marx, and Comte [are recalled] as attempts to ‘reframe’ HoR in more ‘purely etic terms’” (Ungureanu 2022: 219). I sincerely ignore what to make of the nature and tone of such statements. First, I do not know what could possibly justify the reviewer’s choice to single out as something remarkable the trivial fact that an etic approach (that is, a critical, outside-in perspective) has been adopted for a scholarly work. Second, the quotation from my book is wrong. After citing Xenophanes’ renowned fragment DK21B15 (KRS 169), I wrote the following: “as anyone sufficiently acquainted with ancient historiography should know, critical thinking, atheism and agnosticism, in many different forms, have always coexisted and wrestled with religious institutions and dogmas”, and I referred the interested readers to four additional works for a “cognitive and historical rebuttal of the idea that agnosticism and atheism are merely modern ideas inapplicable to ancient cultures” in both the main text and an end note (i.e., Minois 1998; Geertz and Markússon 2010; Whitmarsh 2015; Ambasciano 2016a; cit. from Ambasciano 2019: xiv and 178, note no. 3). As to the other names, they occur forty pages later in a quick biobibliographical list that include Charles de Brosses, John Ferguson McLennan, Henri Hubert, Marcel Mauss, William James, and Friedrich Nietzsche. These names are preceded by Friedrich Engels, Max Weber, Bronislaw Malinowski, Émile Durkheim, and Sigmund Freud, while many more follow (Ambasciano 2019: 31). Do I have to apologise to Ungureanu because I dared include the names of intellectuals and scholars who wrote about religion in etic terms in a book about the history of the academic and scientific study of religions?

Both passages from Ungureanu’s review feature select adverbs and adjectives (“telling”, “tellingly”, “unsurprisingly”) exploited by the reviewer to create a supercilious and quarrelsome tone without ever discussing the in-depth history of all the disciplines preceding and accompanying the historical development of the History of Religions that I carefully reconstructed in my book. Instead, Ungureanu relies quite lazily on the most eye-catching sentences from the Preface and some excerpts haphazardly chosen here and there to suggest and evoke structures of feeling and negative emotional reactions in the readership of his review. Additionally, of the hundreds of scholars and bibliographic works I cite and quote from in my book (some of which in painstaking detail), Ungureanu singles out some specific and fleeting names with the malicious intent to evoke a fallacy of materialistic guilt by association – which, in 2022, truly boggles the mind. Darwin, in particular, is a real bête noire for Ungureanu. According to Ungureanu, I purportedly am

“under the impression that Darwin ‘falsified’ natural theology as ‘an untruthful epistemological enquiry and relegated [it] to pseudoscientific neo-creationism (p. 10)’. This is mere assertion, and he [i.e., Ambasciano] provides no evidence to support the claim. According to Ambasciano, Darwin was a great historian, in the sense that he took history “seriously”—and by “seriously” Ambasciano means of course “naturalistically” (Ungureanu 2022: 219).

Again, the quotation from my book is partial and wrong. In that introductory passage, I drew a contrastive analogy between the historical courses of natural theology and the incipient academic study of religion(s) which would eventually lead to the birth of the History of Religions, and I specifically wrote that

“while natural theology has been falsified as an untruthful epistemological enquiry and relegated to pseudoscientific neocreationism (contra Roberts 2009), HoR [i.e., the History of Religions] is atypical in that, contrary to its predecessor (the Victorian science of religion which we will tackle in the next chapter), it has been triumphantly accepted at the High Table of academia (Ginzburg 2010). In the process, HoR has also become a safe haven for those natural theologians who work in the Humanities (Ambasciano 2014; Ambasciano 2015; Ambasciano 2016a)” (from Ambasciano 2019: 10-11).

First, how could Ungureanu see in this brief passage outlining a set of complex collaborative historical processes the presence of Darwin and Darwin alone is beyond comprehension. As to the “evidence” Ungureanu wanted me to “provide”, it is outlined in the passages and references supplied in my book (in particular in Chapter 3, pp. 37-53, as well as on that very page he cited from – if only he had bothered to pay more attention) [1] . Otherwise, the burden of proof for any other claim pertaining to the status of scientifically discredited and epistemically unwarranted neo-creationist doctrines of all sorts rests solely on Ungureanu’s shoulders.

Second, biologist and historian of science Frank J. Sulloway made a convincing case for considering Darwin as “the greatest historian of all times” decades ago. Evolutionary biologist and historian of science Stephen J. Gould (1941-2002) similarly explored this idea too, as I acknowledge in my book. I thank Ungureanu for tentatively assigning the paternity of this concept to me, but unfortunately I did not come up with it (Ambasciano 2019: 37-38; see Sulloway 1998: 366 and Gould 1986).

Finally, as a historian by trade, I seriously ignore what other “serious” academic and historiographical approach to history is able to provide a sufficient epistemic warrant other than a “naturalistic” or lato sensu social-scientific viewpoint. This begs the question: is Ungureanu sarcastically implying that a historiography of any academic endeavour dealing with religion should instead adopt either a theological or a teleological (Whiggish or degenerative) approach? And, conversely, that any naturalistically-minded study is not “serious” enough? Whether or not the use of such terms and tone betrays the presence of a fideistic mindset alien to historiographical method and theory (see, e.g., Fischer 1970), Ungureanu appears to be disciplinarily ill-equipped to understand the core message of my book. In fact, I claim that he completely misunderstood the problems I set out to explore in my volume. To set the record straight, An Unnatural History of Religions focusses on the “demarcation problem” in the international academic discipline known as History of Religions and adjacent fields, the Lakatosian degeneration of scientific programmes within those academic confines, the cultural and historical contexts, the historical and socio-cognitive contexts that made any resistance to science so successful in these field(s), and the birth of both Religious Studies and the Cognitive Science of Religion as a result of disgruntled and disappointed historians of religions carving their own path out of the field. By the way, this was foreshadowed in the Humean play on words that is integral to the title of the book, which evidently went over Ungureanu’s head (cf. Ambasciano 2018a; Ambasciano 2020a; Ambasciano 2020b).

Misquoting profanities for shock value

None of the complex historiographical, cognitive, and epistemological settings I examined in An Unnatural History of Religions is reported in Ungureanu’s review, to the point that its misrepresentation of my book appears to be borderline offensive. As a matter of fact, Ungureanu makes a caricature of my book, once again extracting some lines from the Preface while omitting the context, basically reducing it to the following: “For [Ambasciano], the current ‘HoR is replete with bullshit,’ and thus ‘HoR must go’” (Ungureanu 2022: 219). As any epistemologist knows, “bullshit” is an academic concept advanced by Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Princeton University Harry G. Frankfurt which I used to define, as per the part of the quotation from my book Ungureanu conveniently omits,

“the disregard for truth and the willingness to engage in fakery and postmodern ‘instant revisionism’ for the sake of it – and for prestige and fame as well (Latour 2004: 228; see Frankfurt 2005, and Pigliucci and Boudry 2013). When this combines with genuine, but equally fallacious, fideism, the result is explosive” (Ambasciano 2019: xvii; cf. 139, 168, 170, 176; key examples of such trends in the current History of Religions are available in Ambasciano 2016b and Ambasciano 2018b: 143-144).

Ungureanu might find personally distasteful Frankfurt’s choice of the term in question, but this does not change the fact that it is not an insult – it is a well-researched epistemological concept strictly tied to “post-truth”, which is defined in my book as “the very act of holding as true whatever it is that someone might believe in notwithstanding the lack of evidence – even in the face of contrary evidence” (Ambasciano 2019: 146; see refs. provided on p. 145). Stating otherwise and omitting the passages where I explain this in detail is mischievous and dishonest.

Secondly, the fact that the discipline known as History of Religions is in need of a radical change is, again, uncontroversial. History of Religions has been in a constant state of crisis at the very least for half a century, and this is a fait accompli among insiders, so much so that dissatisfaction with this status quo prompted scholars to migrate elsewhere and establish the entirely new fields known as Religious Studies and Cognitive Science of Religion between the last decades of the 20th century and the early Noughties – all topics I painstakingly treated in my book and that Ungureanu chooses to ignore (e.g., Penner and Yonan 1972; Lawson and McCauley 1993; Grottanelli and Lincoln 1998; Strenski 2015: 82; Martin and Wiebe 2016: 221-30; cf. Leuba 1912: ix–x).

Eliade, the “chief enemy”

The rest of Ungureanu’s review is equally shallow. Ungureanu claims that my

“chief enemy [sic!] is Mircea Eliade. According to Ambasciano, Eliade’s work ‘became the morphological-phenomenological reference par excellence’. He claims that ‘Eliade brought to a close the metamorphosis of the HoR from incipient science to fully fledged pseudoscience’ (p. 116)” (Ungureanu 2022: 219).

Again, these are far from being “my” idiosyncratic claims. This set of assertions (except the admittedly weird “chief enemy” bit, which is a rhetorical flourish designed to polarise the readership further) is supported by well-known biobibliographical and disciplinary enquiries in both History of Religions and Religious Studies – all dutifully cited in my book. For instance, the fact that “Eliade’s work ‘became the morphological-phenomenological reference par excellence’” was already acknowledged when the Romanian-born scholar was still alive by both his supporters and detractors (Ambasciano 2019: 96, passim; cf. Ambasciano 2014). The Eliadean transformation of the trademark phenomenological and morphological approach, already suffering from chronic issues, into a degenerative research programme had been suggested by many an author in the last decades of the 20th century (see the bibliographies provided in Ambasciano 2014 and Ambasciano 2019). As far as I know, I merely was the first scholar to fully examine this suggestion from an epistemological and cultural-epidemiological perspective (Ambasciano 2018a) – as far as intellectual attribution is concerned, this much rings true to me. However, when Ungureanu attributes the paternity of the “Eliade effect” to me, he is wrong – again (Ungureanu 2022: 220): as I clearly acknowledge in another sentence from the same passage Ungureanu clearly overlooked, it is Russell T. McCutcheon the one who came up with this label (McCutcheon 2003: 207-208); I only developed it by adding a socio-cognitive and epidemiological layer to it (Ambasciano 2019: 176).

As to the problems the discipline of the History of Religions had, and to some extent still has, to face, McCutcheon noted the following, echoing and expanding a commentary authored by Roger Corless (1993): “it is only by addressing th[e] theoretical, methodological, and ideological strategies [inherited from the past] that we can close the Eliadean era with any dignity at all, and thereby make room for a newly invigorated field of study” (McCutcheon 2003: 209). However, as I have shown in my book, the chronic issues affecting the discipline run much deeper, and if Ungureanu sincerely believes that Eliade is the discipline’s nemesis or the be-all-and-end-all of the History of Religions and all its problems, I don’t even know what to say – he might as well have read an entirely different volume.

Finally, after a backhanded compliment (“Ambasciano is very much aware of the literature on the history of HoR”), Ungureanu also misattributes to me with a reproachful tone the “point” according to which no one among all the Comparative Religion forerunners and disciplinary precursors I cited in my volume “‘can be considered a historian of religions lato sensu, [o]r a historian stricto sensu” (p. 33)’” (Ungureanu 2022: 219). I merely followed both a claim advanced by Eliade himself (e.g., Eliade 1984: 13) and a series of seminal works – in particular Grottanelli and Lincoln (1998), Wiebe (1999), Masuzawa (2000), and Gilhus (2014) – which helped me made sense of the puzzling fact that historians of religions have so far failed to identify an agreed-upon list of common intellectual ancestors for their own discipline (all works cited in Ambasciano 2019: 33).

A provincial outlook

The ending of Ungureanu’s review acknowledges my “erudition” but paradoxically ignores it (for the second time) and adds that I have allegedly “misunderstood the origins of the ‘scientific’ approach to studying religion” (sic!) (Ungureanu 2022: 220). I have already suggested above how Ungureanu is quite likely a victim of the Dunning-Kruger effect when it comes to judging the history of academic fields for which he seemingly lacks any real expertise. In this case, his opinion acts as a bait-and-switch strategy to insert his own off-topic take on the “conflict thesis” as it is approached in the theology-friendly and often pro-religious field of Religion and Science (e.g., De Cruz 2021) – it goes without saying that this is not one of the topics discussed in my book. To cut a long story short, according to what Ungureanu writes in his review, the conflict between religion and science from the mid-to-late 19th century onward was merely an internecine war firmly set within the Protestant tradition, with “Protestant writers attempting to undermine institutional religion” (Ungureanu 2022: 220). While I strongly suspect this to be an instance of the fallacy of the single cause (with the benefit of the doubt of it being dictated by word limit), unlike Ungureanu I don’t claim to be an instant expert in other fields, so I suspend my critical judgment as I am currently unable to verify his assertion.

However, Ungureanu also adds that “many of the alleged cofounders of the ‘conflict thesis’—the idea that science and religion are at odds—relied heavily on incipient comparative study of religion and mythology” which, in turn, “depended on theological developments during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and was largely produced by Protestant writers” (Ungureanu 2022: 220). Again, even if I assume that the first sentence about the intellectual background of those scholars Ungureanu does not bother to cite is correct, surely Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico (1668-1744), so important for the “incipient comparative study of religion and mythology”, was not an Anglophone Protestant writer, was he? Neither was Frenchman Bernard Fontanelle (1657-1757), am I right? What should we make of atheist and agnostic scholars, then? Or, moving forward in time, what about the Italian, Austrian, and Dutch trailblazing schools of History of Religions and their disparate ideas about the relationship between science and religion? Were the scholars involved all influenced by Anglophone and Protestant ideas concerning the “conflict thesis”? (Ambasciano 2019: 64-91; for Vico, Fontanelle, and other important forerunners see Ambasciano 2019: 23-24; for a wider panorama, see also Feldman and Richardson 2000.) One of the goals of my book was to show how international and deep the roots of the comparative, academic, and critical study of religions actually are. Clearly, Ungureanu completely missed the point.

Additionally, if Ungureanu implicitly recognizes that the knowledge of the field he labels as “comparative study of religion and mythology” (which would be later known as History of Religions) is a prerequisite to understand the “conflict thesis” as well as other historical and cultural contexts, why did he put the cart before the horse and let his preconceived notions about the “conflict thesis” in the Protestant setting anachronistically colour his understanding of the international development of the academic and scientific study of religions as a whole? I believe that Ungureanu’s provincial disregard for actual historiographical facts, as well as his playing fast and loose with sources (including my book) in as much this suits his views, disqualifies him from being considered a serious scholar.

In cauda venenum

It gets even worse, because what follows is quite possibly one of the most perplexing collections of sequential statements I have ever encountered in all my professional career in the field. Here it is in extenso:

“As Julie Reuben pointed out in The Making of the Modern University (Chicago, 1996) [Reuben 1996], by separating natural theology from theology, and thus jettisoning ‘dogmatic theology,’ early American scholars of religion only ended up ‘reconstructing’ or ‘redefining’ Christianity. As science was reconstructed from a Baconian to a Darwinian model, religion was reconstructed along similar lines. But this only resulted in losing confidence in the unity of truth. The ‘post-truth’ world Ambasciano decries is the legacy of nineteenth-century liberal Protestants who refused to abandon religion as a central concern of higher education. Many of his academic heroes, such as the late Jonathan Z. Smith, Bruce Lincoln, Donald Wiebe, Tomoko Masuzawa, and Russell T. McCutcheon, were educated in the new synthesis provided by mainline Protestants teaching at institutions such as Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and Chicago. So, one wonders if Ambasciano is, in the final analysis, biting the hands that fed him” (Ungureanu 2022: 220).

First of all, Ungureanu misunderstood Reuben’s book about the “influence of the American interpretation of the German model of the university on the study of religions in the modern American setting, which involved the marginalization not only of religion but of morality”, an achievement more recently challenged for different reasons by both postmodernist scholars and religious intellectuals (Wiebe 2016: 187, note n. 6; see also Wiebe 1999: 93-97; cf. Sharpe 1986). Therefore, Ungureanu’s nostalgic longing for a time when creationist natural theology was still en vogue, as well as his claims about the suggested pitfalls resulting from the adoption of the “Darwinian model” in “science” (as a whole?) and the value-laden sentence about the lost “confidence” in the “unity of truth” by a “reconstructed [Christian] religion” as its main consequence, are unfounded, epistemically unwarranted opinions at best and non sequitur-adjacent brouhaha at worst.

Second, Ungureanu’s assertion on “post-truth” is historiographically bonkers. While the various aspects of the phenomenon are themselves historically recurrent (Ambasciano 2019: xii), strictly speaking post-truth is a modern political development tied to the rise of the ultranational radical right, with its ultimate roots in the anti-democratic weaponization of fake news through mass media communication and its proximate contemporary development in the current “onlife” environment where digital and analogical merge seamlessly (Ambasciano 2019: 97; Ambasciano 2021; on the concept of onlife see Floridi 2015). As I recalled in the very last page of my book, Carl Sagan correctly foresaw the imminent explosion of post-truth, its proximate causes, and its societal effects in a now-famous passage dating from the mid-1990s. Since its import clearly escaped Ungureanu’s grasp, I believe the extraordinary passage is worthy of being reproduced here in full:

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness” (Sagan 1997: 28; cited in Ambasciano 2019: 178).

Third, Ungureanu’s list of scholars and institutions backfires as a misguided vehicle for a jaw-dropping blend of fallacies (truth by authority and the genetic fallacy), according to which scholars (the “heroes” in Ungureanu’s mythological world of belligerent factions he’s projecting onto my book) who studied at prestigious institutions perhaps originally tied to religious congregations, or whose historical-religious teachings were once founded on theological tenets, should dare not stray from the properly humble and theologically or disciplinarily right path. Such a sensationally retrograde antiscientific judgment should have no place in any Western, modern, and secular nation-state whose constitution is based on the distinction between Church and State (Copson 2017). But this might be too charitable a reading. All the individuals Ungureanu cites are indeed poststructuralist, postmodernist, or scientifically-oriented Religious Studies scholars who deconstructed those “mainline Protestants’ teaching[s]” and fought hard to disenchant, update, improve, and clear the academic study of religions from all sorts of emic perspectives (i.e., uncritical, inside-out points of view), including pseudoscientific, religious, political, and theological biases (and not just Protestant ones). Moreover, and as far as I can reconstruct, only one university from the list provided by Ungureanu figures in a cited scholar’s cursus studiorum (i.e., Bruce Lincoln’s Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, under the supervision of Romanian-born, Orthodox historian of religions Mircea Eliade – certainly not a “mainline Protestant”; Ambasciano 2019: 133; cf. 93-116) [2]; none of the other institutions the reviewer cites in his red-herring digression figures as an alma mater of those scholars he chooses to include. Finally, as it should be as clear as daylight upon reading my book, I do share many, if not most, of those scholars’ concerns and criticism about History of Religions, so if Ungureanu was trying to play a divide et impera strategy against academic scholars dealing with the critical and scientific study of religions it is only fair to declare that his ill-thought-out plan was abysmally unsuccessful. So, the knowledgeable reader of the review is left wondering what on Earth was the rationale behind the weird inclusion of those scholars and universities here, at the very end of such a poorly conceived and rather uninformative review.

As if this epistemic noise was not enough, Ungureanu cryptically caps it all by adding: “one wonders if Ambasciano is, in the final analysis, biting the hands that fed him”. Try as I might, I keep on failing making sense of this ad hominem metaphor: is Ungureanu implying that I am an ungrateful colleague, a deconstructionist vampire who feeds on the works of more accomplished and religiously pious scholars like “the late Jonathan Z. Smith”, Lincoln, Wiebe, Masuzawa, and McCutcheon? That is not just factually wrong, as I have already noted above, but it borders insanity (except for those scholars being “more accomplished” than I am, which is obviously true). If that’s the case, not only did Ungureanu fail to understand my book (and, at this point, I feel I am justified enough to ask if he even truly read it), but he also spectacularly failed to understand even the most basic tenets of the academic disciplines I examined in my volume.

Moreover, and for the record, I wrote An Unnatural History of Religions as an academically unaffiliated scholar who previously did research and taught as visiting lecturer at the university in one of the most secular countries in Europe (Czech Republic); prior to that, I also earned my PhD in another country where theology chairs at public Universities were officially abolished in 1873 and where the separation between Church and State was enshrined in 1947 in the Constitution (Italy). Based on such a typically European cursus studiorum (outlined in both the Acknowledgements and the back cover of my book, on top of it all), how could I ever be labelled as ungrateful or hypocritical? Or, trying to unpack Ungureanu’s poorly developed thought from another perspective, what should I be grateful for when it comes to select North American Universities or outdated theological teachings? I sincerely cannot make heads or tails out of such hocus-pocus, but something so cavalier, provincial, and sloppy is what you likely get when the author is not qualified as an expert neither in the history of Comparative Religion nor in the relationship between History of Religions and the History of Science, and who spectacularly fails to follow the Rapoport’s rules for writing a book review, which is nothing less than a capital sin for a prestigious venue such as Isis. Let this rebuttal be a teachable moment for all those who want to engage in reviewing and criticising books comme il faut by ending it with Daniel C. Dennet’s version of Rapoport’s rules (Dennett 2013: 33-34) – you’re welcome.

“You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, ‘Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.’

You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

You should mention anything you have learned from your target.

Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.”

Notes

A more concise, 750-word reply to Ungureanu’s review was sent as a Letter to the Editors of Isis: A Journal of the History of Science Society for publication. UPDATE 22 February 2023: the Letter is now available online.

[1] Ungureanu even manages to report an incorrect year of publication for my book, writing “2018” instead of “2019” as clearly indicated in the volume’s colophon.

[2] Additionally, Smith and Lincoln also studied at Haverford College, PA (Ambasciano 2019: 131 and 133), an academic institution originally established by the Religious Society of Friends – and Quakers are not considered mainline Protestants.

Refs.

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2014. Sciamanesimo senza sciamanesimo. Le radici intellettuali del modello sciamanico di Mircea Eliade: evoluzionismo, psicoanalisi, te(le)ologia. Rome: Nuova Cultura. https://doi.org/10.4458/3529

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2015. “Mapping Pluto’s Republic: Cognitive and Epistemological Reflections on Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem.” Journal for the Cognitive Science of Religion 3(2): 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1558/jcsr.27091

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2016a. “Mind the (Unbridgeable) Gaps: A Cautionary Tale about Pseudoscientific Distortions and Scientific Misconceptions in the Study of Religion.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 28(2): 141–225. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-12341372

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2016b. “(Pseudo)science, Religious Beliefs, and Historiography: Assessing The Scientification of Religion’s Method and Theory.” Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science 51(4): 1062-1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/zygo.12303

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2018a. “Politics of Nostalgia, Logical Fallacies, and Cognitive Biases: The Importance of Epistemology in the Age of Cognitive Historiography.” In Evolution, Cognition, and the History of Religion: A New Synthesis. Festschrift in Honour of Armin W. Geertz, edited by Anders K. Petersen, Ingvild S. Gilhus, Luther H. Martin, Jeppe S. Jensen, and Jesper Sørensen, 280-296. Leiden and Boston: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004385375_019

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2018b. “Comparative Religion as a Life Science: William E. Paden’s Neo-Plinian New Naturalism.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 30(2): 141-149. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-12341414

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2019. An Unnatural History of Religions: Academia, Post-truth, and the Quest for Scientific Knowledge. London and New York: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350062412

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2020a. “The Sisyphean Discipline: A Précis of An Unnatural History of Religions.” Religio. Revue Pro Religionistiku 28(1): 3-20. http://hdl.handle.net/11222.digilib/142823.

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2020b. “From Gnosticism to Agnotology: A Reply to Robertson and Talmont-Kaminski.” Religio. Revue Pro Religionistiku 28(1): 37-44. http://hdl.handle.net/11222.digilib/142826

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2021. “An Evolutionary Cognitive Approach to Comparative Fascist Studies: Hypermasculinization, Supernormal Stimuli, and Conspirational Beliefs.” Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture 5(1): 23-39. https://doi.org/10.26613/esic.5.1.208

Copson, Andrew. 2017. Secularism: Politics, Religion, and Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Corless, Roger. 1993. “After Eliade, What?” Religion 23(4): 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1006/reli.1993.1031

Dennett, Daniel C. 2013. Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. London: Penguin.

De Cruz, Helen. 2021. “Religion and Science.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta. URL https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/religion-science/

Eliade, Mircea. 1984 [1969]. The Quest: History and Meaning in Religion. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Feldman, Burton and Robert D. Richardson, Jr. 2000 [1972]. The Rise of Modern Mythology: 1680-1860. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Fischer, David Hackett. 1970. Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought. New York and London: Harper Perennial.

Floridi, Luciano. 2015. “Introduction.” In The Onlife Manifesto: Being Human in a Hyperconnected Era, edited by Luciano Floridi, 1–3. Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04093-6_1

Frankfurt, Harry G. 2005. On Bullshit. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Geertz, Armin W. and Guðmundur I. Markússon. 2010. “Religion Is Natural, Atheism Is Not: On Why Everybody Is Both Right and Wrong.” Religion 40(3): 152–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.religion.2009.11.003

Gilhus, Ingvild Sælid. 2014. “Founding Fathers, Turtles and the Elephant in the Room: The Quest for Origins in the Scientific Study of Religion.” Temenos: Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion 50(2): 193–214. https://doi.org/10.33356/temenos.48457

Ginzburg, Carlo. 2010. “Mircea Eliade’s Ambivalent Legacy.” In Hermeneutics, Politics, and the History of Religions: The Contested Legacies of Joachim Wach and Mircea Eliade, edited by Christian K. Wedemeyer and Wendy Doniger, 307–23. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Gould, Stephen J. 1986. “Evolution and the Triumph of Homology, or Why History Matters.” American Scientist 74(1): 60–9. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27853941

Grottanelli, Cristiano and Bruce Lincoln. 1998 [1984–1985]. “A Brief Note on (Future) Research on the History of Religions.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 10(3): 311–25. https://doi.org/10.1163/157006898X00286

Latour, Bruno. 2004. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30(2): 225–48. https://doi.org/10.1086/421123

Lawson, E. Thomas and Robert N. McCauley. 1993. “Crisis of Conscience, Riddle of Identity: Making Space for a Cognitive Approach to Religious Phenomena.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 61(2): 201-223. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1465310

Leuba, James H. 1912. A Psychological Study of Religion: Its Origin, Function, and Future. New York: Macmillan.

Martin, Luther H. and Donald Wiebe (eds.). 2016. Conversations and Controversies in the Scientific Study of Religion: Collaborative and Co-authored Essays by Luther H. Martin and Donald Wiebe. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. 2000. “Origin.” In Guide to the Study of Religion, edited by Willi Braun and Russell T. McCutcheon, 209–24. London: Cassell.

McCutcheon, Russell T. 2003 [2001]. The Discipline of Religion: Structure, Meaning, and Rhetoric. London: Routledge.

Minois, Georges. 1998. Histoire de l’athéisme. Les incroyants dans le monde occidental des origines à nos jours. Paris: Fayard.

Penner, Hans H. and Edward A. Yonan. 1972. “Is a Science of Religion Possible?” The Journal of Religion 52(2): 107–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/486293

Pigliucci, Massimo and Maarten Boudry (eds.) 2013. Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Reuben, Julie A. 1996. The Making of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Roberts, Jon H. 2009. “Myth 18: That Darwin Destroyed Natural Theology.” In Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion, edited by Ronald L. Numbers, 161–9. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Sagan, Carl. 1997 [1996]. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. London: Headline.

Sharpe, Eric J. 1986 [1975]. Comparative Religion: A History. Second Edition. London: Duckworth & Co.

Shermer, Michael. 2002. “This View of Science: Stephen Jay Gould as Historian of Science and Scientific Historian, Popular Scientist and Scientific Popularizer.” Social Studies of Science 32 (4): 489-524. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3183085

Strenski, Ivan. 2015. Understanding Theories of Religion. Second Edition. Malden, MA and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sulloway, Frank J. 1998 [1996]. Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives. London: Abacus.

Ungureanu, James C. 2022. Review of “Leonardo Ambasciano. An Unnatural History of Religions, Academia, Post-Truth, and the Quest for Scientific Knowledge. London: Bloomsbury.” Isis: A Journal of the History of Science Society 113(1): 219-220. https://doi.org/10.1086/717909

Wiebe, Donald. 1999. The Politics of Religious Studies: The Continuing Conflict with Theology in the Academy. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Whitmarsh, Tim. 2015. Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World. London: Faber and Faber.

Wiebe, Donald. 2016. “Claims for a Plurality of Knowledges in the Comparative Study of Religions.” In Contemporary Views on Comparative Religion: In Celebration of Tim Jensen’s 65th Birthday, edited by Peter Antes, Armin W. Geertz, and Mikael Rothstein, 181-192. Sheffield, UK and Bristol, CT: Equinox.